Lauren W. Deutsch, Sochi

[Y]ou’ve seen her about town, demurely coiffed and impeccably dressed in a shimmering kimono of a refreshing hue of green upon which seasonal grasses and a single flower bud blossom onto her obi. Perhaps you know her by her stage names, poetic impressions conjured up by her esteemed patrons, among which she counts many of Kyoto’s elite – the current grand masters of traditional hospitality and those for over 16 generations before. She is invited to be present in complex rituals that honor the most noble of Japan’s warriors. Her renown is jealously guarded as one would a fine songbird of rare voice. A sweet confidence marks her beguiling gestures. Even after one chance meeting, one is left with an impression that is deep and full.

She is, of course, “Matcha-sama” – Japan’s beloved emerald empress of high traditional culture, the national muse whose substance is the finest powdered camellia sinensis. Even in Kyoto, the undisputed center of the Japanese tea world, wherever she goes, she is in a class by herself. Her reputation is impeccable, albeit “Old School”; she is outnumbered by the likes of upstart “Punky Poky Bobacha-chan” and “Frappalattechino-chan”.

If you think that chanoyu, the Japanese tea ritual, is primarily about enjoying the flavor of matcha … I have a bridge to sell you! Let’s call it the ultimate Japanese “urban myth”. Making matcha – mixing of hot water and a tiny bit of carefully selected, hand-picked young green tea leaves in powdered form – is merely the premise for a refined social gathering. Unlike oenophiles who can wax poetic about the taste factors of their beloved wine, chado practitioners, folks who make the Way of Tea their Way of Life, are hard pressed to discuss the distinct taste characteristics of dozens of comparably prepared teas from each other of the same grade.

So what’s the fuss about a tea ceremony? Why are there so many different products marketed if there’s no discrimination? Why has making and sharing a bowl of matcha been one of the prime markers of Japanese culture for over half a millennium? Does one have to study 10+ years and make thousands of bowls of tea to get a handle on the taste? Maybe. Maybe not.

The Taste of a Bowl of Emptiness

Tea is not a game and not an art;

one taste of tea refreshes and purifies

and gives enlightenment to the universal law.

–Murata Shukô (1423-1502)

Tea – enjoyed in powdered leaf form – was imported to Japan from China along with Rinzai Zen Buddhism by Yosai in about 1192 A.D. and was first planted at Kozanji Temple in Toga-no-o in the northwestern region of Kyoto. Other temples began to plant tea for their own consumption, as did the imperial palace in the early 9th century.[1]

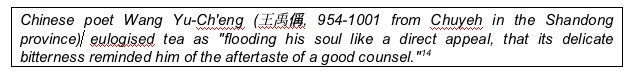

Tea was popular among the monastic set for its medicinal effect; its high level of caffeine kept them clearheaded and awake during long periods of sitting zazen meditation. In China, back then, tea was relegated to the “bitter” category of the Five Element Theory[2] of Traditional Oriental Medicine, thus good for the heart. (Only recently has the West adopted pungency as the official fifth taste sensation. Umami as its known is a signature Japanese flavor projecting a broth-like, pungent “heartiness” sensation associated with fermented and aged foods. More about umami to come!)

Priest Myô-ei Shonin went to the trouble to delineate “Ten Virtues of Tea”[3], but none were about the taste.

Tea …

Has the blessing of all the Deities.

Promotes filial piety.

Drives away the Devil.

Banishes drowsiness.

Keeps the Five Viscera in harmony.

Wards off disease.

Strengthens friendships.

Disciplines body and mind.

Destroys the passions.

Gives a peaceful death.

Rather than also bring back methods of cultivation of the plant, they told us how to cultivate the mind: there is … no … discrimination … no … nose, tongue, body … smell, taste …” in emptiness. It may be a good recipe for enlightenment, but not for gourmands. Murata Shukô (1423 – 1502), renowned among his peers for dozing on the zafu meditation cushion, one day finally woke up, jumped up, declaring, “Chazen ichi mi” – “Tea and Zen are the same taste!” and exchanged the dark, smoky zendo for a life of tea drinking in the secular world. He got points from his iconoclastic teacher priest Ikkyu, also a proponent of chanoyu.

Tea, the medicine and the Chinese-inspired ways to prepare it ritually, began to make its way out of the monastery into the Buddhist-influenced secular world of warlords and merchants, particularly through Takeno Jô (1502-1555), and his famed student Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591). Shoguns from the late Ashigakas through the Toyotomis, especially the egomaniacal Shogun Hideyoshi Toyotomi, became patrons of chajin tea practitioners and the latter became formal members of their courtly retinue. Tea utensils trumped the plant in value, and these objects often were coveted more highly than real estate as spoils of war victories. There are tomes written about the crafting and collecting of Chinese tea caddies and Korean tea bowls, as well as the rise of domestic craft production in ceramics, metal, fine fabric, lacquered wood, bamboo and other materials for the performance of the ritual.

Elaborate tea gatherings were refined compositions of hospitality that demonstrated the host’s skills in incorporating fleeting seasonal elements into ichi go ichi e … “One time. One meeting.” The practice became a living embodiment of the cultivation of wa, kei, sei and jaku, harmony, respect, purity and tranquility. Everything about tea – the architecture, landscaping, culinary histories and more – has been fair game for meticulously-researched connoisseurship … except the taste of tea itself. While never completely disassociated from temple life, the preparation of chanoyu morphed into chado as a secular vocation, now 16 generations long, of folks with impeccable taste, and hundreds of thousands of their followers.

The Earth’s Gifts: A Matcha Primer

Like wine and perhaps even more like beer, creating fine matcha has everything to do with rootstock / plant, the soil and its geographic placement, weather, techniques of growing, manufacturing and storage, all of which will impact its taste. Here are some hints about such variables as encountered in tea production today.

Location. Location. Location.

Fine matcha is usually associated with the town of Uji in the southern end of Kyoto, near Byodo-in Temple. With a deep bow to the history and tea commerce, today it’s a lovely tourist town full of little tea shops situated along the river that shares its name, once considered a source of potable water excellent for chanoyu. Outside the “downtown” are the tea plantations and processing and storage facilities. Matcha that bears the distinction as “Ujicha” may have been grown in Kyoto, Nara, Shiga and Mie Prefectures and “finished” in Uji. Ujicha is most associated with the more conservative, formal tea schools that were patronized by the elite chado families and Shogunate, such as Ippodo (founded in 1717), Kanbayashi (1500), Koyamaen (late 1600s), and relative newcomer Ryuonen (1875).

On the other hand, Aiya Saijoen, founded in 1888, obtains its tea leaves from 850 year-old family farms in Nishiio,Aichi Prefecture..These tea plants enjoy a terroir benefitting from being near three rivers and the soil is characteristically less “heavy” with minerals than that of Uji. Yet, to all but the most experienced tea tasters, terror influence is imperceptible, unlike, for example, the impact of limestone in the soil nourishing a fine pinot noir, for example. While Nishio claims to have hosted the largest tea ceremony[4] , Shizuoka Prefecture, which hosts a large international tea exposition[5], boasts being the largest tea-growing region in Japan, having been producing for over 650 years.

Vintage

The tea growing cycle goes from spring through fall. Unlike wine and fermented teas which improve with age, and like beer which is best enjoyed fresh, matcha is usually consumed over a single year’s time. Its taste declines with age and improper storage and handling.

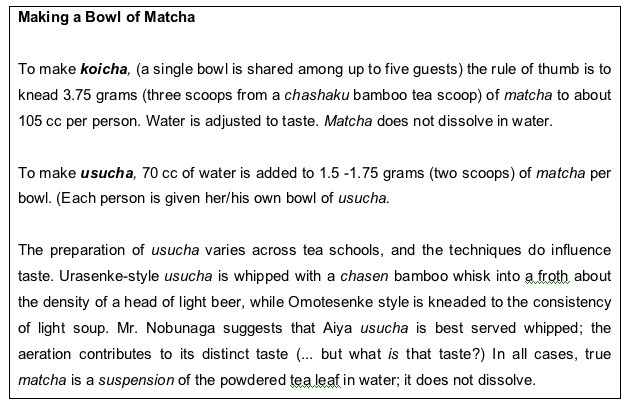

Root Stock and Soil

According to Atsushi Yasui-san of Hibiki-an[6], gokoh, samidori, and komakage varietals of camellia sinensis are best suited for producing gyokuro, the finest grade of tea from which the youngest (top) “two flags and a spine” (two leaves and a bud) are hand-selected to be dried, sorted and finely ground into matcha. Koicha, matcha prepared in “thick” concentration of powdered leaf to water, is from root stock of about 200 years of age; usucha, “thinly” prepared matcha, comes from younger plants. Good drainage is critical as well, so tea plantations tend to be on slopes.

High quality gyokuro tea trees need to be fertilized (fish meal, bean meal) about three times as much as other teas, such as those for sencha. The soil’s nitrogen content (whether natural or increased through fertilization) impacts the amount of L-theanine, an amino acid that is source of the “sweetness or its deliciousness” umami taste. “Perhaps what gives tea its is the way that L-theanine stimulates the taste-buds.”[7] Pesticides are hardly ever used, even on “non-organic” products.

Organic production is of great current interest. All matcha was originally organically produced. Today, Japan strictly regulates its production of agricultural products labeled as such. With modern fertilizers, there can be “super” matchas, ones especially high in nitrogen in which the taste more “grassy”. The organic teas are less sweet, according to Shiro Nobunaga, sales director of Aiya America, Inc[8]. There are ways to challenge nature to produce a more broadly pleasing product, balancing bitterness and sweetness in the most pleasing proportions.

Weather

The history of weather – most notably rainfall (about 1,500 mm / year) and high day and night temperature contract (with high expectancy of mist) – will affect the quantity of tea available. Nobunaga noted that in 2007 and 2008 the volume was less due to rainfall issues, but the quality was maintained.

Finished in Darkness and Hand-Picked

For the last 20 – 30 days prior to picking, mid April to May – traditionally 88 days after the festivities of setsubun a late-winter holiday, the fields of gyokuro plants destined for matcha are covered with progressively applied shades made of reed, rice straw or fiber to a height of about seven feet[9], one layer per week for three to four weeks depending upon weather. According to Mr. Nobunaga, “When you shade the tencha fields, the leaves try to collect more sunlight, thus becoming wider, thinner and softer. This is why when you hand pick these top, young shoots, you get the most resilient green color and also it becomes the finest in particle size when you grind them with the granite wheels. The finer the matcha in particle size, more smooth and creamy the taste and texture (not grainy like the lower grades).”

This unique growing method forces the plant to produce more chlorophyll as it strains to absorb whatever light there is. It also reduces the tendency of L-theanine from turning into catechin, a component of tannin that is connected with shibui, astringency. Both L-theanine and tannin have calming properties, yet matcha has the capacity to stimulate. More L-theanine, an antioxidant, more umami flavor. Modern science has recognized L-theanine to be effective in the treatment of high blood pressure, cancer, heart disease and other ailments. (Remember, the Chinese medicinal system relates the taste of “bitter” with the major organ of the “heart”.)

As noted, tea for matcha is always picked carefully by hand during May, about 88 days after setsubun, the festival marking winter’s end. Like the grape crush, the entire field is picked through until all the leaves appropriate for matcha are picked. There is no second or late harvest. The leaves undergo a variety of manufacturing processes that steam (arrest oxidation and maintain color, flavor and aroma), dry (air and heat) and cut them. The leaves are separated from the stems and veins, with the remaining 10 percent of the plant called tencha. Finally, it is graded by size through a number of winnowing activities and allocated to be suitable for koicha or usucha. Tea for matcha is not rolled like sencha and other infusing teas. Tea for matcha is never rolled, as is common in the processing of gyokuro.

Tea “sommeliers”, as Nobunaga-san calls them, are in charge of carefully blending the tencha plants grown in different types of soil according to “secret formulas” to create blends that are consistent over time, expertly recognizable and which are assigned various product names. No one that I spoke with indicated there being any premium attached to drinking the product of a single tea plant type, or as in the wine world, where vertical (vintage) comparisons are much discussed among connoisseurs and the quality plus quantity of which impact the price.

Grinding

The first grinding occurs in November. Today, as in Rikyu’s time, the tencha is still ground between two horizontal granite stone mill wheels, the only contemporary change is that the wheels are turned by machine at a speed (55 rpm) equal to that of human power. It is estimated that it takes an hour of grinding to produce one ounce of matcha. Not all the tencha is ground at once. Mr. Nobunaga explains that Aiya stores its tencha in refrigerated facilities and grinds it throughout the year based upon the market’s demand. In the “old days”, grinding was done by the tea master prior to serving it.

As would be expected, even in the best storage, fresh tencha destined for matcha will decrease in intensity through the course of the year. For this reason, the chanoyu preparation techniques, especially koicha, will take into account the intensity of flavor; the temperature of the hot water will be allowed to drop before being added to matcha in the late spring through early fall when the strength of the sensitive leaf has diminished. Matcha is usually sifted about three times to render it as fine powder without clumps just prior to placing it in a ceremonial container.

The First Tea Gathering of the Year

In the most formal of settings, such as those observed by the elite chajin families, their empty chatsubo ceramic tea jar is delivered to the chashi tea producer who puts small bags (75 gms) of appropriate variety of koicha (finest grade for the formal, thick presentation) into the jar and fills the rest with tsumi-cha (tea leaves) for the informal, usucha (thin preparation). He puts on the lid, seals it and marks it with his hanko stamp. The chatsubo is placed back into its box to which is affixed a list of its contents by the chamei poetic name of the tea. The jar is returned with a gift of thanks to the owner and arrives with much anticipation and fanfare.

The arrival and opening of the chatsubo is the commencement of first private chaji tea gathering of the new year, coinciding with the opening of the tea room’s ro sunken hearth. In Chado: A Tea Master’s Almanac10, Sasaki Sanmi, a journalist and Urasenke household intimate, says that it is a lifetime’s greatest honor to be invited to witness the kuchi-kiri breaking of the seal of the chatsubo and tasting the first chanoyu. The opening of chatsubo tea container is done in the presence of guests, who admire the container and wrappings. The chaseki tea ceremony meal is then served and eaten in silence so that the sound of the milling wheels grinding the new tea may be heard. Only then will the temae ritual presentation begin, first with kencha ritual offering of thick tea to the ancestors, Buddha, etc., followed by a single bowl of koicha shared among several guests, followed by individual bowls of usucha, thinly prepared tea.

Much Ado About Matcha

Concerns (or lack thereof) by the general population about the agricultural and manufacturing processes of tea are no different than any food these days, but, because of the tea ceremony, there has been much ado about matcha that rivals, and arguably, exceeds, that of the West’s obsession with wine. To that end, our dear Matcha-sama might be considered the ultimate “guest” of a chaji formal tea gathering, with the humans merely there to extend the welcome and adore her. But, at the conclusion of the hours-long event, we will know very little about her, save her name.

What’s in a Name?

The finest matchas, both as koicha and usucha, are given chamei tea names, often awarded together in pairs, by a renown tea master or temple. Rather than hint at the taste, they serve merely as marketing ploys. These identifications function much the same as names of perfume: Channel’s #4 or #5, for example. Without our having prior experience of comparisons, as it regards the taste, these names don’t help any more than Shukô’s describing the taste of tea as “Zen”. Tea students are taught the names of their affiliated school’s preferences and are encouraged to purchase these products. The tea’s chamei, however, will be taken into consideration when planning a a tea gathering’s poetic framework (including the sentiment of the scroll displayed in the tokonoma, the poetic name of other utensils, etc.).

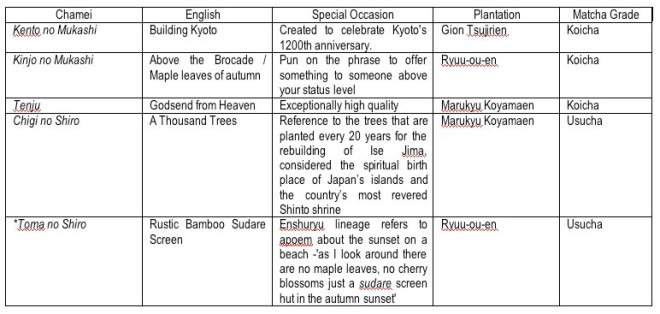

Particular blends that bear chamei may be produced over several years and even through several generations of tea masters, such as the following list of currently available teas11 demonstrates:

Other names may reference an auspicious occasion, specific poetic reference, etc.

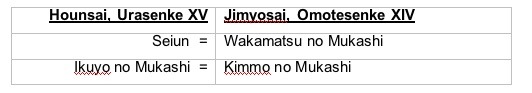

To make matters even more confusing, a single tea blend may be given several names, by each of several different grand tea masters. Examples from Ippodo are:

In addition, special matchas are often created in limited “editions” and quantities for special events, such as Ippodo’s Shin Shun Wakamatsu-no-mukashi koicha, and Shin Shun Seiun usucha were available only from December 2007 until mid January 2008, as long as supplies lasted.

Names often have distinguishing terms that identify koicha from usucha. Mukashi, in the former, refers to “tradition” or “classic,” and hints at the older root stock, are selected to create the highest quality koicha. In the case of usucha, the word shiro, literally “white”, is nuanced to conjure up a sense of freshness or renewal, a characteristic value of Japanese Shinto, as in the reference noted above to Chigi no Shiro. 12

Tea Tasting “Contests”

According to Murai Yasuhiko[13], “The occurrence of tasting “contests”, recorded as early as the Kamakura period (1192–1333), were known as tôcha, emerged as a result of the great expansion of tea cultivation. In contract to the Chinese practice of judging tea by its quality, the concomitant spread of tea drinking in this age, the tôcha of Japan were competitions aimed at distinguishing among teas according to the regions where they were grown”, usually comparing Toga-no-o and to others, similar to that of the popular incense contests.

As tea culture grew increasingly more popular among the secular classes and distanced from the internal discipline of the temples, things got wildly out of hand with heavy wagering and extravagances, associated with entertainment, crossing social boundaries. Shukô admonished against turning the ritual preparation of tea into a “game” around the same time that a growing profession of tea master was emerging, as was noted earlier. Tasting “rules” were incorporated into cha-kabuki, more formal, conservative tea gatherings

Omotesenke’s VII Grand Master Joshinsai Tennen, 1705-1751) and his older brother, Urasenke VIII Oiemoto Yugensai Itto (1719-1771), adopted into the family to continue the lineage, created “contests” for tea tasting pastimes within the context of the Zen teachings of Daitokuji’s Priest Mugaku Soen. Still practiced today as one of the training exercises of tea students, chakabuki is a formal exercise to help develop one’s sensitivities to discriminate one tea from another[14], but still not to describe the taste per se.

Cha-kabuki procedure is done in a large tea room among at least four guests, a host and a recorder. The challenge is to distinguish the identities of three koichas in a blind tasting after having sampled two of them with their chamei, poetic names revealed. The third, unknown tea, is literally called kyaku, guest. While there may have been verbal discussions afterwards as to why one taster was confident in his/her selections, the written records simply record their guesses. there are no hints as to indication of specific flavors that contributed to the choice.

Yasui-san of Hibiki-an, an Uji tea company, advises that, “There were certainly the flavor distinctions not only vertically but horizontally on matcha a long time ago. The vertical distinctions just depend on the quality. Today, there is almost only vertical distinction on matcha,” as opposed to sencha and gyokuro types. “Therefore, today, it is not easy to enjoy “matcha chakabuki”.

On Our Own

After all this, we’re back where we started. What is the taste of matcha? How can we distinguish the difference from one product to another? Does it really matter?

A survey of English language matcha websites – retailers / wholesalers and producers produce a consensus that better quality = better taste = higher price. The higher priced matcha have a more complex, smoother, rounded flavor and a gentle, natural sweetness, but that’s about it for descriptors. Bitterness, the original medicinal quality associated with the health of the heart – is completely missing. The difference in flavor among the blends of matcha is more subtle than with steeped teas. Compared to sencha, matcha is weak in astringency and strong “mellowness”, due to its being shaded during the final weeks of growth.

Koicha can be made thin with very satisfactory results, but usucha is not usually prepared in koicha concentration as it is a bit more bitter. Tea shop owners have suggested that a “beginner”, whether formally a student of chado or someone who just wants to drink matcha, should try the lesser expensive grades first, perhaps feeling that the most subtle taste notes (?) would be lost and money wasted.

The chakabuki section of Urasenke’s multivolume encyclopedia of temae (AKA the “green” books — Japanese language, only) the first taste of koicha should be with the tip of the tongue, noticing the burst of flavor and then one must recollect the impression it leaves in the hara, the depth of center of one’s being, two fingers below the navel. A similar sentiment was expressed by the late (as in deceased) “Tea Man” in his online blog, who suggested developing a personal set of parameters, an alphabetic collection of constant points of reference which, when combined, create a glossary and, ultimately, new a composition narrating an experience, “as though tea talks to one as it allows itself to be drunk.”

Everyone says it’s subjective, but why go to the trouble if there’s no distinction? Flavor it is well known, is a factor of many variables not yet discussed. The “Tea Man” waxes poetic about influence of “nose”, volatile aromas, vs the nonvolatile, action in the taste bud department.

Even without the fanfare and fuss of the kuchi-kiri, opening up a new tin of matcha, is a sheer delight: The “whoosh” of breaking the aluminum seal bursts forth with thesweet aroma of young mowed grass, perhaps full meadow sparkling with a freshness of summer rain. In the winter, when the tearoom air is driest from the heat of the ro sunken hearth and the ko incense is heavier, the tea is relatively fresher and brighter in taste than in the summer, full of humidity and a breath of sandalwood incense mixes with the fresh air of the open window. This is why no perfume (or scented anything) should be worn when drinking matcha.

Matcha is definitely the flavor of green … but which one? The answer remains elusive! No matter what grade of matcha one buys, the deeper / brighter the hue, the fresher the tea. When it starts to take on a brownish trait, it is no longer fresh. To insure that tea remains fresh, it should be stored away from heat, light and dampness, about 59 degrees Fahrenheit. Matcha should be stored in the freezer until it is time to open it, then taken out and left to rest for 24 hours until any possibility of moisture will settle before it is opened. What is open should be enjoyed within a month at the longest. The color, flavor and aroma diminish almost immediately upon exposure to light and oxygen.

Ingredient-grade matcha is also being marketed by producers who export, in the hope of getting a piece of the popular matcha colored / flavored products being sold as having additional nutritional benefit. The forthright producers will label their product accordingly. Because one eats the tencha leaf, there is significantly more value than if tea is steeped. Like all foodstuffs, however, the fresher the product and the finer the grade, the better it will be. The quality of this lesser grade is not suited for even an usucha experience.

I once purchased a tin of matcha from a Japanese market, sitting on the shelf next to several types of leaf tea. (It clearly hadn’t been well stored – in the freezer), and the price reflected a “bargain”. I used it for practicing temae, one of the many chanoyu procedures, on a night of the full moon and ended up doing a calligraphy of tsuki moon rather than drinking it. This is not to say that higher grades of matcha couldn’t be used as an ingredient, but if the taste is insignificant, there’s no point to the added expense.

Other Variables Influence Taste

Water: If you’re going to experiment with a variety of matchas or to enjoy one to its fullest, there are a number of variables related to the water that can significantly impact the taste. After all, the beverage is nothing but providing the yu hot water for the cha tea. Water temperature determines whether you taste more of one over the other. Soft water (i.e. with less mineral content) is best to use for making matcha or any tea, to reduce the influence of mineral / metallic impressions overpowering the tea taste itself. Tea lore informs us that it is best to draw water (fresh from a sacred well, of course, in the wee hours of the morning. There is even a water “tasting” opportunity within some of the tea procedures. There is a method of preparing usucha using a muzusashi freshwater container that is a tsurube, wooden well bucket draped with shimenawa with gohei a rice straw rope and white paper cuttings. This indicates to the guest that the host has gone to trouble to secure special water about which she or he might inquire.

Water Temperature: The kama iron kettle used to heat the water – its will also impact the taste of the water and thus the tea. Even the speed in which the water has reached its boil will make a difference. Using sumi charcoal during the tea ritual (with its replenishment mid-way) will have the water boiling at just the right speed and thus temperature: emitting the sound called matsukaze “wind in the pines” at just the right moments. Electricity, however, is consistent and creates large bubbles and too rapid a boil. If the water is too hot, the bitterness will be more apparent than the sweetness. Water should be brought to a boil and then simmered for about five minutes to about 75-95 C before adding it to matcha. Over-boiled water is depleted of oxygen and creates a “flat” taste.

Shape of Drinking Vessel: Taking another lead from wine, the shape of the tea bowl may have something to do with the experience of taste. The Riedel glass company has designed wine glasses that are shaped to deliver a specific varietal of wine (e.g. pinot noir vs. merlot) into one’s mouth to land at the appropriate place on the tongue where the taste receptors are most sensitive to that particular nuance. In the winter, tea bowls tend to be taller while in summer, wider. One reason given is that the beverage stays warmer in the winter, but in effect, the diameter of the lip affects the embouchure, the shape of the mouth.

Condition of the Palate: Unlike wine, however, matcha is not best enjoyed with food. It is served after kaiseki the special multi-course meal created for chaji formal tea gathering. The final “course” is a “moist sweet”. Afterwards the guests take a break, leaving the tea room. Upon return, they are served a bowl of koicha prepared to the consistency of melted ice cream, and, whether another break is provided or not, they enjoy a “dry” sweet and a bowl of usucha, one per guest.

In these days of Green Tea Mousse Pocky, jars of iced decaffeinated matcha spiked with lemon grass and pomegranate essence, and bobba-ed chai lattes in fat-straw pinioned take-out cups and Tea Ceremony kits sold next to Zen Garden kits in gift shop windows under hot spotlights … the effort made to find fine matcha and to take care in its preparation, will reward you with a wonderful benchmark with which to expand your experience and make up your own mind.

Perhaps the author of The Book of Tea, Okakura Kakuzo (aka. Tenshin), the aesthete who is credited with bringing the deepest sentiment of chado to America at the turn of the 20th century, said it best writing The Book of Tea: “There is a subtle charm in the taste of tea which makes it irresistible and capable of idealisation.” The fact that tea, especially matcha, like any muse, has captured the imagination of an entire culture through time and space is reason enough to explore its storied past and its availability in our time from any vantage. I pukku sashiagemasu!

Footnotes:

1 Varley, Paul and Kamakura, Isao (eds.) Tea in Japan: Essays on the History of Chanoyu.(University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1989)

2 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Umami

3 Sadler, A.L., Cha-no-yu: The Japanese Tea Ceremony (Tuttle Publishing, Boston, 1962, p. 94)

4 According to Guinness Book of Records, the largest simultaneous tea party consisted of 14,718 people drinking matcha during a single Japanese tea ceremony was arranged by the City of Nishio and the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Nishio on October 8, 2006. This is definitely a far cry from the 1.5 mat tea hut of Rikyu’s fame.

5 www.pref.shizuoka.jp/a_foreign/english/tea/index.html

6 www.hibiki-an.com

7 www.omotesenke.jp/english/chanoyu/1_3_3.html

8 www.aiya-america.com is the North America outpost for the Japan-based corporation.

10 For a full description of the kuchi-kiri see Sanmi, Sasaki, Chado The Way of Tea: A Japanese Tea Master’s Almanac, Shaun McCabe and Iwasaki Satoko translators. (Tuttle, 2002, Boston). p 551-2. In all its 742 pages, however, there is a significant lack of any reference to how matcha actually tastes! See Kyoto Journal 54 (2003) for a review of this otherwise remarkable book of seasons by this article’s author.

11 Translated by the wonderful folks at what was formerly teatoys.com. Sources of fine matcha via the web include Ippodo, Kanbayashi, Marukyu-Koyaman-en, Marukyu-Koyamaen and Shorai-en. All are impeccable in their sources – all are Ujicha, ensuring fresh, high quality matcha.

12 Kakuzo, Okakura (Tenshin), The Book of Tea

13 “The Development of Chanoyu” in Tea in Japan, ibid

14 Urasenke International Association, translators. Tankosha Editorial Department, eds. (Tankosha Publishing Company, Ltd., Kyoto 2007). Similar exercises were developed to develop a sensitivity of distinction for ko incense.

15 www.sugimotousa.com/?q=brew