Lauren W. Deutsch

“I have no doubt that, within ten years, the fundamental way of tea will

die out. When it dies out, people in society will believe, on the contrary,

that it is flourishing. The miserable end—when it becomes completely

a matter of worldly amusement— is now in sight. How lamentable it is!

… it is out of step with this latter age.”

—Sen no Rikyu, 1589

Thus spoke my tea ancestor, Rikyu (1522-1591) two years before he was obliged by his über patron and student, the Shogun Toyotomi Hideyoshi, to commit seppuku. It would appear that the progenitor of the XVI generations-long San Senke (Three Sen Families) dynasty was aware that his modest, contemplative practice of cha-no-yu, literally boiling water for matcha, might turn into an excuse and means by which to acquire and promote one’s copious material possessions. Was he naive enough to believe that his students would reach the heart of his wabi-infused tea practice, to make do with a few essential utensils of subtle beauty at hand and retire to rustic huts deep in the woods?

It is likely that he was considering both the intangible and material aspects of the enterprise that became Cha-do, the Way of Tea. Compare the aesthetics of his tiny, still extant Tai-an tearoom, dating from 1583, in Kyoto and Hideyoshi’s long-gone portable ogon chashitsu (golden tearoom), created in 1585 and eventually destroyed in the Osaka Castle fire of 1615. Dare we infer that Rikyu, a Zen monk, was attached to the idea of this “fundamental” chado, not that Way of Tea? Perhaps, but his signature notion of wabi and sabi—well worn, essential, imperfect, quiet, and impermanent objects—has reached us to this day through 16 unbroken generations of Senke practitioners.

While he left no personally written records, there is no doubt that Rikyu was a change agent, a catalyst who maintained his signature philosophy of transmuting boiling water to make tea into a profound experience of wa, kei, sei and jaku (harmony, respect, purity and tranquility) throughout his life. He captivated the attention of the most notorious warlords of the time and convinced them that mastery of chanoyu was the penultimate mark of an action hero; carving tea scoops would be a better use of their swords. His contemporary adherents were counted among the vanguard of the sukisha (civic, economic, religious, cultural and military leaders) and also included wealthy farmers and merchants, individuals described by Kamakura Isao as a “force behind Civilization and Enlightenment policies.” Over time, the body of practitioners has changed drastically with the economic and social ebb and flow. By the end of the Edo period, “even” women and foreigners were counted among practitioners and licensed as instructors.

Rikyu’s legacy has reached us in the 21st century through the careful management of his resources by three branches of the family established by his spiritual heir, his grandson Gempaku Sōtan, the third generation grand master of the lineage. It was he who established Rikyu’s aesthetic legacy for all time. He reclaimed and consolidated his grandfather’s property and, upon his retirement, bequeathed it in thirds to the next generation. This was the start of the San Senke, the three families that directly can claim direct blood lineage from Rikyu: Omotesenke, Urasenke and Mushanokojisenke (named after the front, back and a nearby street of the original estate). Affectionately known as “Wabi Sōtan,”, he also preserved Rikyu’s chadogu (tea utensils), including some made by his ancestor’s own hand. Among various tasks, Sōtan evaluated newer utensils, putting his stamp on the lids of their boxes, and gave gomei (poetic names) to items that he deemed suitable for use in tea practice. He also regulated the teaching and practice in the name of Rikyu.

The San Senke have sustained themselves for nearly half a millennium by teaching temae (tea-making procedures), overseeing the presentations of tea gatherings, being the arbiters of all things of good taste by bestowing certification of gonomimono (favored items) and other related intangible cultural exchanges and material objects, from chashitsu (tea huts) to matcha itself. Currently the San Senke grandmasters are Zabosai, Sen Sōshitsu XVI (Urasenke), Jimyosai, Sen Sōsa XIV (Omotesenke), and Futassai, Sen Sōshu XIV (Mushanokojisenke). Each one has sustained their progenitor’s practice in a fundamentally similar but slightly This way, not That way!

The history of chanoyu and its impact on Japan is long and anecdotes abound as a result of practitioners’ keeping meticulous diaries of who came to tea, what dogu were used, the meals served, etc. In 1757, the term oiemoto (grand master) became fixed as a cultural norm for these families. Paul Varley notes two reasons that this system caught on formally. The first, “… a swelling demand for the arts largely from amateurs practicing chanoyu as an avocation or who wished to enrich themselves culturally,” and that the system represented an “attempt to harness—and profit from—the large new clientele for these elegant pastimes (yogi”).

Successive generations of oiemoto cultivated new, innovative ways to take advantage of Japan’s social, cultural and economic shifts by adjusting the practice, for example by creating procedures requiring formerly unimaginable dogu, such as tables and chairs! Of course, students required more lessons to learn these new ways.

As the number of people engaging in the practice grew or declined with the vicissitudes of Japanese socio-politico-economic life, so did the market for dogu. While Rikyu was hard at work tempering the lust for power and prestige, nonetheless tea gatherings became excuses for showing off one’s material possessions. Some utensils were so coveted they were more valuable than a plot of land when demanded by the victor of a battle. In 1587 Hideyoshi had the chutzpah to host the Great Kitano (Tenmangu) Tea Gathering to which he brought all of his omeibutsu (precious Chinese utensils) for all to inspect and expected his approximately 1,000 guests to do the same.

Rikyu’s minimalist aesthetic, however, favored a return to chanoyu’s humble origins in Zen Buddhist monasteries. His teaching promoted mitate, appropriating an object for other than its original purpose, using a worn, weathered Korean rice bowl that still had some life left in it and perhaps an interesting backstory. Artisans working in wood, clay, bamboo, metal, silk, paper and lacquer, picked up on the burgeoning market and began to fashion the vessels that would enable the host to combine the five elements into a once-in-a-lifetime “ichi go, ichi e” for the guest.

Rikyu began to commission a number of local artisans to handcraft items to contain the essential elements of chanoyu (fire, wind, water, earth). Among the many workshops creating everyday essentials, those he worked with repeatedly were able to make one-of-a-kind utensils that expressed his wabi tastes. These artisans became known as shokka to tea practitioners. In addition to transactional relationships, these family workshops established symbiotic social relationships with their patrons, and each other, in a few cases even intermarrying. Together, these multi-generation lineages of shokka and Senke have risen and fallen in tandem like a double-stranded helix of Japan’s cultural DNA.

The shokka each comprise one workshop and did not evolve into “schools” as did the tea families and each generation generates new works through utsushi (emulation of the previous), a developmental training method common to all ranges of Japanese artist genres.

The shokka group of craft families with the longest relationship to the San Senke include Eiraku (ceramics), Hiki (laquered paper), Raku (pottery), Kuroda (bamboo), and Nakagawa (repousse and cast metalwork), all tracing their ancestry back to Rikyu’s time. Later Senke generations embraced Onishi (cast metal), Komazawa (wood joinery), Nakamura (laquerware), Tsuchida (textiles), and Okumura (paper) family workshops. Other crafts workshops have been patronized but none so consistently.

The shokka each comprise one workshop and did not evolve into “schools” as did the tea families. They preserve collections of their historic wares (several with museums open to the public), and each generation generates new works through utsushi (emulation of the previous), a developmental training method common to all ranges of Japanese artist genres. Through the process of replicating the techniques and style of a noted or established master, the craftsman as artist experiences first-hand the technology, material requirements, and necessary aesthetic understanding, to create a new “original” item. Utsushi promotes a dialogue between the artist and the masters of the past, connecting past, present, and future. This may also frame the teaching practices of successive generations of tea masters.

As in the tea schools, the responsibility for carrying on the artisanal traditions have been carefully passed down, usually from father to a son (though currently three holders of lineage are women). The successor is chosen for his/her technical mastery of skills, as well as his/her capacity to sustain the lineage by maintaining its material resources. Producing and training an heir, a wakasosho (young master) is essential. In addition to the land on which the workshop stands, the inheritance includes in situ sources of raw materials and caches of those that require long aging periods (e.g. clay, drying timber), proprietary patterns and designs, and notebooks (including records of how and when objects were used), fabrication tools, pattern books, models, molds and equipment (such as forges, looms, etc). Above all, one inherits the relationships along the supply chain and patronage, especially the tea masters themselves.

A true disciple was thought to inherit the “‘complete’ knowledge and authority of his master in entirety (kanzen soden).” Each of the craft houses has their own form of transmission, much of it closely guarded oral and privately archived resources. In the case of Raku teabowls, Kakunyu (Kichizaemon XIV, 1918-1980) admonished, “In a single line of transmission, what a father teaches to his child is that he will not teach.” His son, the current oiemoto, Kichizaemon XV, was challenged to figure out how to work with the materials, tools and techniques at his disposal to achieve a representative but distinct outcome. This skill and sensitivity is nurtured by examining past pieces and determining the nuanced taste of the current oiemoto of the tea families. The work of Atsundo, the current wakasosho, is already well regarded.

Each August, the current heads of the shokka as a group undertake ochugen (a formal visit) to the oiemoto of each of the San Senke to learn of proposed activities for the coming year. As esteemed members of the greater tea community / extended “family” members, they will also attend such formal gatherings as memorial anniversaries of Rikyu, Sōtan and other prominent Senke family members. Occasionally, the craft houses produce unique objects to commemorate special observances, such as Rikyu’s 400-year memorial.

At the beginning of each month, the oiemotos visit each grand tea master more informally to get feedback on new works and ascertain their patrons’ current needs. Many konomimono (favored pieces) that become part of the oiemoto’s aesthetic legacy may be identified at these casual conversations, and a gomei (poetic name) granted by the tea master. Practitioners of a particular tea school are encouraged to inculcate current or past oiemoto’s nuanced tastes and may acquire similar items. These affinities are recorded and studied by tea students, art historians, restoration experts and curators alike.

The toriawase (selection of dogu for chanoyu) must take into account the lineages of the ware used, and the provenance of some pieces is formally discussed (haiken) during tea gatherings. When objects that display an acute sensibility of the first iteration and its reinterpretation are displayed and used together in the tearoom, a new, sharper perspective is cast upon the craftsman. According to Kristin Surak, in Making Tea, Making Japan, “Aficionados take pains to ensure that utensils made or signed by more recent oiemoto do not usurp those made by one further back in the lineage.”

Japanese art, particularly the traditional forms, were hit particularly hard by bunmei kaika, the all-out Westernization movement of the early Meiji period, and went into a state of creative decline at the end of the 19th century. The new middle class that was moving into cities was hungry for modern life and Western-style art. At the same time, Westerners were mostly only showing interest in the exotic exported Oriental Japonisme.

In 1919 a marketing campaign by Mitsukoshi department store to generate business at its Osaka branch gallery featured the work of the abovementioned 10 shokka; this was the first time they were promoted as Senke Jisshoku, the “Ten Craftsmen (houses) of the San Senke.” While they still received commissions from these and other tea masters for one-of-a-kind wares, they found a new market in this emerging strata of consumers hungry for prêt-à-porter examples from the masters. Whether a buyer knew how to utilize these objects in their “proper” context for tea or just enjoyed them for utilitarian or bragging rights was not a barrier to consumption.

Ninety years later, in 2009, Japan’s National Museum of Ethnology (Minpaku) celebrated the “Senke Jisshoku” with a major exhibition at which the current lineage holders had the opportunity to speak about their traditions and, interestingly, to nominate favored items from the museum’s global collection.

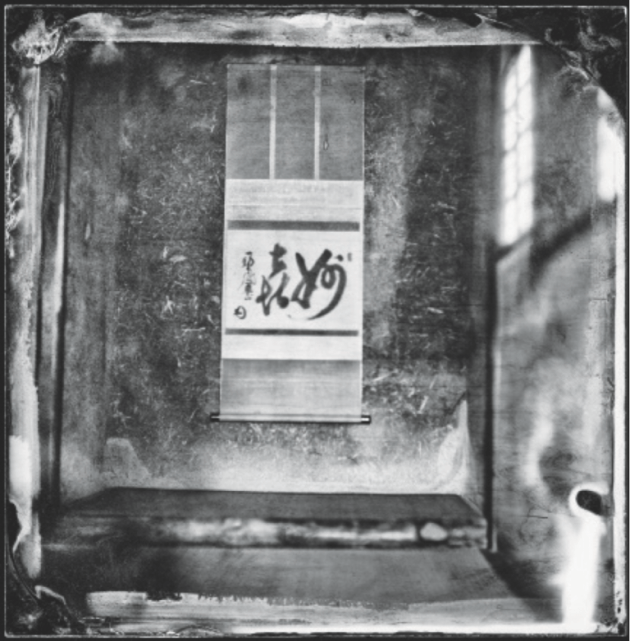

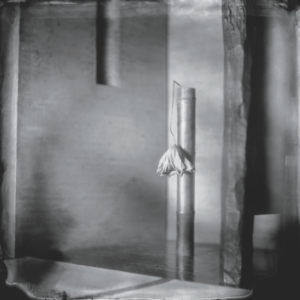

[1] The Tai-an (or “Waiting Hermitage”) Tea Room at Myoki’an Temple (built c. 1582), situated in the town of Oyamazaki in Kyoto Prefecture, is the only extant example of a tea house believed to be built by Sen-no Rikyu. Rikyu was the founder of the Urasenke School of tea and is considered the father of Japanese tea ceremony. This rustic and humble two-tatami-mat space embodies tea master Sen-no Rikyū’s wabi-cha aesthetic that emphasized simplicity and local wares. At the time, the space’s design was wholly unprecedented: the inner pillar of the tokonoma alcove is concealed behind the wall plaster, and the surface of the wall itself is rough with straw fibers. The imperfections in the wooden pillars are also radically integrated into the design.

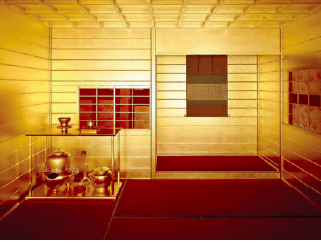

[2] This contemporary tea room was built in 2001 as part of the Raku Kichizaemon Pavilion, dedicated to the work of the 15th generation head of the Raku ceramics family in the Sagawa Art Museum. The tea room is divided in two: one smaller room is fully submerged in water, and a larger one seems to float above it. Raku Kichizaemon XV himsel conceived of the tea room’s design,, based on the idea that guests should sit as close to the level of the water as possible, just as humankind should see eye-to-eye with and coexist harmoniously with nature. Recycled lengths of bamboo from dismantled farmhouses blackened by smoke form the ceiling of the tea room, and old Balinese timber pillars stand at the corners of the alcove. Echizen washi paper is plastered on the interior walls and black granite from Africa marks the front of the alcove, while the walls are black concrete.

Thus, as described by Morgan Pitelka in Japanese Tea Culture, “from the late 16th century to the present day, representatives of these traditions have been engaged in a constant process of writing and rewriting the boundaries of their own histories, ruling over what is not authentic practice, and editing the material and textual legacies that have formed the core body of culture passed from one generation to the next.”

We don’t know what Rikyu would have thought of the present-day form of chanoyu, but it is likely that he would recognize an attempt to see its greater purpose as embodying the heart of suki, or in Ito Junji’s description, “establishing one’s own existence through one’s relationship with others.”

“Tradition is not simply ‘preservation.’

It is that element in creative art which does not change at its core

but which changes constantly in its expression.”

—Uchiyama Takeo, director emeritus for the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, quoted by Patricia J. Graham, Japanese Design: Art, Aesthetics & Culture

Photography by Everett Brown