[I]n ancient times Buddhist monks following the precept to abstain from the taking of life ate only foods derived from plants; no meat, no fish. Vegetables were boiled or eaten raw with simple seasonings. This vegetarian cuisine was first introduced to Kyōto monasteries from China in the 7th and 8th centuries. It was the founder of the Sōtō sect of Zen Buddhism, Dōgen Zenji, whose groundbreaking work, Tenzo Kyōkun (Instructions for the Cook), sparked further development in the art. By the 13th century, the implements, ingredients and ways of cooking had been cultivated to a high level. In Japan this cuisine came to be called shōjin ryōri 精進料理.

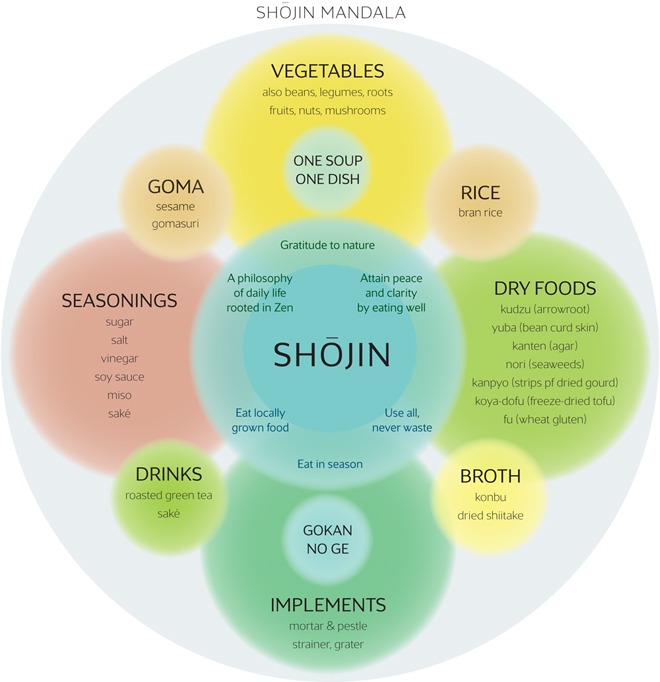

Shōjin food is seasonal, local and authentic (made with natural non-industrial ingredients). It consists of vegetables, grains, beans, sesame seeds, nuts, mushrooms, fruits, wild herbs, seaweed, roots, agar, kudzu and dried or fermented foods. The seasonings to bring out the flavors of vegetables are made with konbu, sugar, salt, vinegar, miso, soy sauce, and saké. Human beings cannot exist without plants. They are miraculous gifts from nature created from sun, air, soil and water. Shōjin practitioners understand this truth and thus endeavor to cultivate respect, knowledge and gratitude for the plant products that provide us with the wonder of life.

To combat growing obesity in the U.S., the 1977 McGovern Report concluded that the diet most suitable for the human body is the pre-18th century Japanese diet (which lacked the technology to include polished white rice.) With the exception of fish and shellfish, the diet bears a close resemblence to shōjin cuisine, incorporating a wide variety of vegetables. Shōjin cooking maintains an excellent balance between taste and health; as part of your daily diet it can purify your body and mind but still provide a highly satisfying dining experience.

1. Engage with the food. Consider how nature’s miracles and people’s hard work have culminated in the creation of the food you are about to enjoy.

2. Reflect upon your day and yourself. Contemplate whether your actions make you worthy of the meal in front of you.

3. Observe whether your own spirit is pure like the food. A mind full of the three greatest evils (greed, anger and ignorance) cannot truly appreciate or savor the food.

4. Chew slowly and enjoy every bite. Good food is medicine. It is a way of rejuvenating and purifying your fatigued body.

5. Be thankful for all, and eat with gratitude. To make and eat good food is part of walking the virtuous path of Buddhism.

Once the monk has meditated on each point, he/she sits upright, puts his/her hands together in prayer, and says “itadakimasu” (a Japanese term used before meals to express gratitude and humility) in a clear voice. Only then can the monk finally take his chopsticks to enjoy his/her food.These five points are based on two important Zen books,Tenzō Kyōkun and Fushuku Hanpō, which prescribe how to prepare and eat food respectively. Both texts were compiled by Dōgen Zenji.

[A]t the heart of shōjin, and indeed most Japanese cooking, is “one soup, one dish” (ichijuu issai 一汁一菜). Rice and tsukemono (pickles) are also served, but are taken for granted and not counted in the phrase. This is also the essential Zen meal, which uses four nested bowls. Simple, yet profound.

[S]pring, summer, autumn, winter. Awaking from the cold winter, new buds receive the gentle light of spring. They bloom and bear fruit in the summer. In the fall rice turns golden and mushrooms grow thick in the mountains. Roots silently fatten beneath the frosted earth in winter.

[S]pring, summer, autumn, winter. Awaking from the cold winter, new buds receive the gentle light of spring. They bloom and bear fruit in the summer. In the fall rice turns golden and mushrooms grow thick in the mountains. Roots silently fatten beneath the frosted earth in winter.

Today artificially cultivated vegetables are available throughout the year with little or no regard for seasonality. When tomatoes are served in wintertime how disastrous it is for them and us! Our bodies should reap the positive energies of the seasons. Shōjin aims to return balance between our bodies and nature based on the prinicples of inyo gogyo (yin-yang and the five elements). Fruits and vegetables, such as tomatoes, eggplant, melon (all classified as the yin element in Chinese cosmology) cool the body in summer. Potatoes, carrots, and radishes (the yang) warm the body in winter. So it is a basic principle in shōjin cooking that we eat seasonal ingredients when they are at their very best. We merely assist with a natural process.

[S]hōjin ryōri is rooted in the concept that the earth and body are inseparable. It is only through attaining a perfect symbiosis with the land that we can truly reap the benefits of the earth.

[S]hōjin ryōri is rooted in the concept that the earth and body are inseparable. It is only through attaining a perfect symbiosis with the land that we can truly reap the benefits of the earth.

That is exactly why the best foods for the body are not imports from far-flung countries, but rather what the local land offers at that particular time of year. Consider the varieties of indigenous food harvested across the globe. Tropical fruits are thirst-quenching and cooling— perfect for a blazing summer day in a sundrenched land, whereas winter harvests are heart-warming and vitalizing— exactly what you would need on a chilly morning in snowy terrain. What is best for the body on any given season, in any given place, is what is seasonal and local. By eating fresh produce, we can adapt to the environment and live in harmony with the earth.

[M]any may think nothing of throwing away carrot skins and radish leaves, but these ‘scraps’ are actually full of highly nutritious vitamins, minerals, and fibers. In shōjin philosophy, it is considered that true gratitude encompasses the whole without producing any waste. Peels, roots, leaves—we are only truly thankful for the food we have when we have eaten and appreciated the vegetable in its entirety.

[M]any may think nothing of throwing away carrot skins and radish leaves, but these ‘scraps’ are actually full of highly nutritious vitamins, minerals, and fibers. In shōjin philosophy, it is considered that true gratitude encompasses the whole without producing any waste. Peels, roots, leaves—we are only truly thankful for the food we have when we have eaten and appreciated the vegetable in its entirety.

True gratitude is also not self-serving. It is something that can become a principle for living, transforming your relationship with your surroundings in general. For example, once you consider eating the whole vegetable, skin and all, it is only logical to choose produce that is grown organically. Choosing food that is free of chemicals and fertilizers is not only a healthy choice, but also an environmentally friendly one too.

Making as small a change as how you eat a single vegetable may lead to greater awareness and gratitude towards the larger ecological

environment.

[T]he suribachi (mortar) is an essential implement for the shōjin practitioner. Grinding sesame seeds—or gomasuri—in the early morning for making sesame tofu with mortar and pestle prepares the heart and mind for the day ahead. It is the shojin practice of meditation: kneeling in the seiza position, relaxing the muscles, breathing with awareness, and grinding in even, circular motions as the aroma of sesame rises in the air.

Made from ground sesame seeds and often served as an appetizer, gomadōfu (sesame tofu) is considered to be the most basic dish in shōjin ryori. The sesame seeds are soaked for a full night in cold water, then ground with precision and care for a full hour. Water and kudzu are then stirred into a paste. The mix is gently simmered over a low heat, kneaded, and then chilled to make the tofu shown below.

Implements next in importance to the suribachi are the oroshigane,a grater, and an uragoshiki or strainer.

[T]he Kyōto-based chef Tanahashi Toshio is convinced that shōjin cuisine will come to the fore this century as the best alternative to our meat-heavy, fat-saturated, and wasteful diets. He believes the age of gluttonous cuisine, of gastronomy, is over and it’s time to add a fourth star to Michelin’s prestigious three-star restaurant criteria of taste, service and atmosphere—one for “health.”

Born in 1960 in Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan, Tanahashi obtained in Agricultural Economics degree at Tsukuba University. He decided to take up the art of cooking, pursuing what he calls “a philosophy that exists within everyday life.” At age 27 he began a three-year apprenticeship at Gesshinji Temple in Shiga Prefecture, a nunnery with a tradition steeped in shōjin cooking. In 1992, he opened Gesshinkyo, a highly-acclaimed shōjin ryōri restaurant in Tokyo. In 2000, he supervised the food preparation for “Honmamon” (The Real Thing), a fictional TV series by NHK depicting the life of a young chef of shōjin cuisine. Tanahashi has been featured in numerous publications including Vogue Japan, Kateigaho, The New York Times, The Sunday Times, The Financial Times and Kyoto Journal.

Tanahashi has been active across the globe, hosting events from Thailand to Brazil and overseeing the Venice Biennale reception party as head chef in 2013. He has been invited to demonstrate his style of cooking at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, and has lectured at the Japan Society in Boston and New York.

Tanahashi has been active across the globe, hosting events from Thailand to Brazil and overseeing the Venice Biennale reception party as head chef in 2013. He has been invited to demonstrate his style of cooking at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, and has lectured at the Japan Society in Boston and New York.

After closing Gesshinkyo in 2007, Tanahashi established the Zecoow Culinary Institute in Kyōto. He has recently retired from teaching “culinary arts and philosophy” (shokugei) at the Kyōto University of Art and Design to pursue his own projects. His books include Shōjin: Wonder of Vegetables (2003), and The Power of the Vegetable: The Time for Shōjin is Now (2008). Until recently, Tanahashi ran a small shop, Sankyō, in central Kyōto where he sold sesame tofu that he made fresh every day.

Tanahashi passionately observes the principle that the art of cooking is not a matter of technique, but rather a philosophy and spiritual striving ingrained in daily life.