Without much fuss, the Irani café has managed to become part of Indian culinary folklore, entrenching itself within the consciousness of specific cities over the past century. But in a current landscape dotted with fast-food hegemony and the rapid erosion of lazy afternoons, is nostalgia enough to carry forth its legacy?

~

The city is yet to awaken. Some of the streets and smaller bylanes stir with barely noticeable pockets of activity—newspaper being bundled and wrapped for neighbourhood-specific deliveries, single-shutter bakeries spreading out their wares for the nightcrawlers and the early morning workforce, a few packs of dogs out to cement their territories, that sort of thing—but not much else. Dawn is on the verge of exploding. Soon, its mellow orange flood of flickering warmth will have encroached upon the eastern fringes of the city, before quickly swallowing everything else in its wake. Here at Café Yezdan though, life is already in full swing.

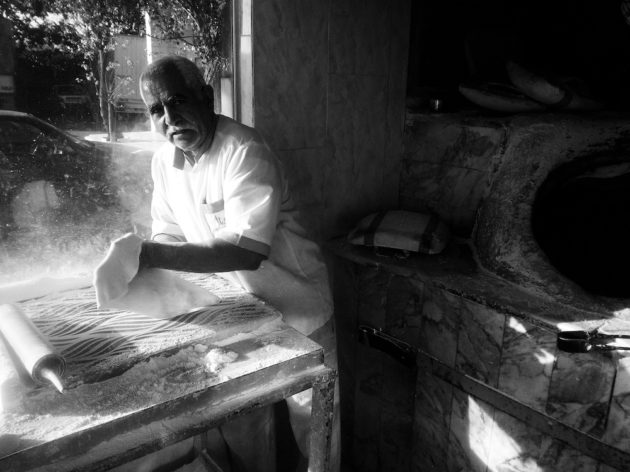

In the constricted quarter that serves as an open kitchen, dough is being kneaded, doused in flecks of flour, and brought to rise on the time-tested profundities of habit; an anticipated menu of food duly emerges. The two young men handling the task go about things with the clockwork dexterity of doctors at surgery. Arriving at my table, variously, are buns both impossibly fluffy and hard as a rock, laced with fresh cream and dollops of butter that sizzle beneath the sway of heat. The lingering effect of something so simple is anything but.

It’s nostalgia, pure and simple. A remembrance, hinged on place and flavour. Sipping from my glass cup filled three-fourths of the way with breathlessly hot, spice-kissed Irani chai, I recognise the fact that this is the exact same feeling I’m accosted by every time I step into a storied Irani café (and each time I’m welcomed by its sibling—the often intertwined Parsi restaurant). It’s gooseflesh and childhood; it’s heritage and laughter; and it has nothing to do with how many times you end up frequenting a café, but everything to do with how often its smells and memories creep up on you without warning as you embark on your journeys through life.

Poona With a Dash of Maska

In my hometown of Poona (a name I prefer over the official Pune, for reasons wedded to emotion and wistfulness), roughly three hours from Bombay (preferred over Mumbai, for much the same reasons), the broken bricks and fading stonework of Café Yezdan have seen and delivered much. As I savour my chai, my eyes drift towards the café’s interiors, now flooded with early morning light and a nearly full house. My brun-maska has long been wiped off.

A Migration Across Cultures

Who can really articulate how it would all have seemed, right at the beginning? Escaping the Great Persian Famine of the 1890s, thousands of Persians embarked on an expedition that would lead them from the cold and uncharted expanses of the Hindu Kush mountain range towards the land then known as Hindostan. Amongst these pilgrims and their quest for survival, was a young man birthed in Yazd, today a Central-Iranian province found at the convergence of the Dasht-e Kavir and Dasht-e Lut deserts. One wonders whether Haji Mohammed Showghi Yezdi himself had any clue that his voyage from Kerman, through to Quetta, and finally arriving at the glittering, clamorous shores of Bombay, would someday culminate in the birth of something known as the Irani café.

My gaze falls on the café’s bentwood chairs and tightly-packed tables; on the odd colonial accents and the few painting and posters freckled with decay; on the plump glass jars at the counter laden with biscuits, rusks, and other childhood treats; and on the menu board on which are scrawled, in large letters, the ‘café specials’—this classic format being your instant zone of comfort in every Iranian café you step into. While Yezdan may not display the round Eastern European tables with black marble tops, those ubiquitous green-and-red-checkered tablecloths, and the high ceilings which usually validate the ID Card of the Irani café, this is very much a favoured child of the same family.

Perhaps the only Irani staple missing from Yezdan whose lack I sometimes bemoan, is the vertical blackboard dotted with a habitually deadpan selection of “By Order” Commandments: “No discount”; “No talking to cashier”; “No picking nose”; “No flirting.”

Yezdi was one of the men who laid the seeds for this cultural infiltration in the simplest of ways: he brewed cups of tea on the sigdi he’d carried with him. The kindled coals at the bottom of the sturdy tumbler imbuing a certain rustic homeliness to their Irani chai, the immigrants would offer them to fellow refugees by way of communal remembrance sessions. Yezdi soon began selling the tea to workers and tourists at Apollo Bunder—Bombay’s port enclave beside the Gateway of India.

Yezdi and his brood, their surnames often bearing the stamp of their native villages (Yezdani, Kermani, Jafrabadi, Khosravi) had, though, already been set a precedent. Over a thousand years before them, Persians fleeing persecution for their Zoroastrian faith from marauding Arab invaders, had fled to India and, over decades, integrated themselves into the cultural fabric of the land. Their origin from the Pars region of Iran too was the decider in their coinage: Parsi. This community was to welcome its brethren many centuries hence, but was to end up following the new arrivals’ entrepreneurial ingenuity in the form of its own cultural productions—the Parsi café and the Parsi restaurant.

Cities and Their Crucial Inheritances

My connection with these cafés, though intensified by the rich historical texturing of both the Irani and Parsi café, has far more to do with the rather more intimate influence of memory and a sepia-dipped filter that has, somewhat artfully, quartered itself within the cinéma vérité of my life.

The camera film unspools to a portrait of entering old Hyderabad’s gates for the first time, and finding a sense of place within the musty yet oddly mellifluous cadence at Farasha. It’s as though the city’s rituals and heritage had gathered themselves for me in the provocative combination of Osmani biscuits and Irani chai, my perch alongside the restless spectacle that is Chudi Bazaar ensuring that the silent sorrows accosting the four minarets of the Charminar were no more than a few steps away

The film unspools further to being tantalised by the aroma of chai again, a hop and a skip away, within the rowdy early morning visage of Shah Ghouse. The camera pans around to the pure, delicious simplicity of life, as summoned by a single bite of perfectly fried lamb samosa at Shahrah—on this occasion, the Makkah Masjid (one of India’s largest mosques, accommodating up to 20,000 worshippers) being the one to cast a divine eye over me.

The Weight of History

My fondness for the Irani café gathers both momentum and context as I move closer to home. From this point onward, the deliciousness of the food and the richness of the tea come at me with reinforced potency. There’s something inherently Indian about having a meal at Britannia & Co. in Bombay, nestled beneath leaves and the preponderance of antiquity amidst the art deco and art gothic offices of Ballard Estate.

It isn’t simply taste; it’s truth. It’s about history (in this case, dating back to 1923), hanging on adamantly, despite an onslaught of the new. It’s about hardiness, with the iconic restaurant having survived even the Second World War’s far-reaching reverberations. It’s about confluence, what with Bachan Kohinoor, the wife of beloved (read irascible) near century-old owner, Boman Kohinoor (who died just over a year ago, aged 97), having introduced her Parsi heritage to the restaurant’s Iranian origins, with voraciously loved staples such as the Dhansak (chicken or mutton swimming in the prosperity of a lentil soup) and Sali Boti (a sharp hit of mutton gravy abounding with the textural volatility of tomatoes, vinegar, and jaggery, decorated with crispy fries).

Most compelling though, it’s about the rousing romance of the Mutton Berry Pulao (with its jewel-like barberries, professedly imported from Iran to this day). It’s a flirtation of the senses, with the tongue revelling in its new-found glory of succulent mutton that slides off the bone, dancing with the kiss-me petulance of berries rich in flair, and the Indian requirement of a thin curry; equally, it’s a feast for the eyes, flitting amongst the light faded green of Britannia’s walls, the crystal chandelier that hangs on in hope, and the distressed remnants of framed photographs.

The Irani café, like its architects, has had to withstand wave upon wave of tribulation. The advent of South Indian udupi restaurants, followed by the deluge of global chains and their formulaic hegemony over local markets, changing tastes amongst a clientele raring for other flavours, and even the changing dynamic of the Irani and Parsi communities themselves, have all forced the Irani café to reinvent, or simply hang on tight. India once was home to over a thousand of these cafés, before that number dwindled in half towards the mid-20th century. Today, there are roughly 100 Irani cafés (give or take a few) left in the land. That statistic doesn’t fill me with gloom though; it fills me with urgency.

Navigations Through Reminiscence

There is an urgency to head to Bombay over the weekend, walk into Kyani & Co., and beneath the 116-year-old stateliness of its high ceiling, meditate on a little thing called legacy. Once there, with the street swagger of a kheema roll and the more refined attractions of a mawa cake disposed of, I would be free to summon the ghost of Raj Kapoor, India’s eternal showman. Kapoor would often drop into Kyani for some bun-maska; through the lingering wisps of the Metro Cinema just opposite, perhaps I would even be able to summon a moving image frame, frozen forever in the folds of time.

There is an urgency to replenish memory, about a café that itself seems wrapped in fond recollections of its earlier incarnation as Café India in the 1920s. There is an instant recall of youthful passions at Jimmy Boy, as pure Parsi staples of Salli par Eedu (a circular bed of fried potato ‘straws’, crowned with a half-fried egg and immersed in chopped onions, tomatoes, and green chillies) and Margi na Farcha (chicken legs coated in eggs and deep fried on the mirth of mild spices) garnish, season, flavour, and accentuate the ingredients within a fledgling weekend love…

… Or of long conversations on art, beauty, literature, and the crucial matter of who’s running away where, caressed over Lagan nu Bhonu—the legendary Wedding Thali brimming with all manner of Parsi goodness. Equally, there’s an insistence on staying behind at Grant Road Station for the profusion of juxtaposition, where a certain Merwan & Co.’s Czechoslovakian chairs abut its Italian marble-top tables, and the can-only-be-desi Bhurji Pav somehow elicits a stolen bygone era, dappled with the silver screen shimmer of film stars.

The Resilience and The Romance

As my memories dart about, across to one final Bombay pit stop on this journey through Colaba’s Fort district, before honing in on Colaba Causeway, there is an urgency now to revel in resilience. My hands glide over bullet holes from the past; a decade ago, Leopold Café withstood a barrage of savagery from cowardly terrorists, and brushed itself off to tell the tale. Those ghastly beasts having long been deposited back in hell, life at Leopold’s sways to its tune, as it always has, sheltered by the looming imperiousness of the Taj Mahal Hotel and the harbourside memorial—the Gateway of India..

Co-owned now by Farzadh Sheriar Jahani and his brother, Farhang, this restaurant may have revamped its original menu, dating from 1871, beyond recognition to embrace a multitude of global tastes from locals, travellers, and foreign expats in love with the scent of its bohemian soul, but it continues to remain an emblem of Bombay: colourful and chaotic, hybrid and hypnotic, perilous and powerful, solicitous and sacred, all in equal measure.

Because We’ll Always Have Home

Having had a healthy jog across timelines and geographical topographies, my memories return to the here and now. Back at Café Yezdan, life persists as it always has, at the delightfully-named Sharbatwala Chowk (‘sharbat’ alluding to a drink prepared from fruits or flower petals, popular in India, the subcontinent, and allied lands; ‘chowk’ referring to an open market or urban area at the fulcrum of two roads). Dawn’s early glow has proved to be a misnomer. A dull, overcast romance now spreads across the skies. Poona preens in the crispness of its weather, and I decide to walk.

I amble past the Chowk, thick in the heart of the city’s Camp neighbourhood, and cut across, to East Street. My mind is still rumbling with the day’s ruminations. I reflect on the Zoroastrians, and later, a smaller number of Iranian Shia Muslims, who have contributed to this true fusion of Indo-Persian ethnicity. I wonder at the thought of the old Aryan chaikhana ritual, once abundant across the Aryan trade routes, having planted itself so firmly in a land and a culture this far away. And I smile at the awareness of a recent resurgence in the Irani café’s fortunes, brought about by both the fierce pull of nostalgia, as well as the entrepreneurial tendencies of a younger generation of Iranis, Parsis, and cosmopolitan Indian café obsessives, each intent on keeping this heritage alive.

In London, Dishoom has been flourishing, stoking the adjectival embers of every major food critic across its Shoreditch, King’s Cross, Carnaby, Covent Garden, and Kensington addresses. Co-founded by Kavi & Shamil Thakrar and Adarsh & Amar Radia, the brand’s homage to an Indian culinary mainstay blends style and an Indian heart, with near aristocratic servings of nostalgia. Most pertinently though, be it in the note-perfect food, in a ravishing visual palette of curious nuggets from history—retro fittings, old faded posters, peeling walls redolent of the bygone—and charm constructed on the edifice of irreverence, or in its loyalty to a Bombay of the then and an India of the now, the homage stays true.

Closer home, SodaBottleOpenerWala has done much the same, harnessing this stubborn yearning for the Irani café among patrons and gourmands young and old, into a mouth-watering assemblage of heritage, humour, and whimsy.

What I Think About, When I Think About Home

I pick up a box of wine biscuits from Kayani, and step out through its brick-arched, history-laden portico. They’d sold out their Shrewsbury biscuits by 9:25, as they often do. I wander along on the yet unpeopled East Street and the parallel-running Mahatma Gandhi Road in a delicious dream. The sounds of boyhood banter and first crushes wrapped in auburn foil waylay me through the smells, flavours, bentwood chairs, and much-loved balcony of Marz-o-Rin Café, its chutney sandwiches and cold coffees having marked their place in history.

Snapshots from another borough in Poona, Deccan, come sweeping in as well—Café Goodluck’s literary escapades and an open kitchen that always gave you the impression it had been cleaned only once—at its inauguration in 1935.

Places and faces and dishes and meals carrying exotic lineage come rushing in like waves. Café Olympia, golden chai, Diamond Queen, khade chammach ki chai (tea filled with enough mounds of sugar to make the spoon “stand”), the green chilli and mint leaves marinated, banana leaf-steamed pomfret of Patra ni Machchi, the doused-with-longing condensed milk perfection of Lagan nu Custard…

The Jazz of Remembered Things

The day slips away. It’s Thursday night now. Notes of jazz, served neat, and whiskey, served equally so, dart in and out of conversations. The Shisha Jazz Café is that bruised love you can never quite let go. This storied institution serves up live jazz on Thursday nights, tapping talent both fresh and fabled for its identifiable jazz bouquet.

Through its confluence of thick foliage, sprawling two-levelled space, global travellers and bohemians, and sweet-scented romance, Shisha has, over the past 17 years, assumed its place among the ‘world’s best live music’ venues. Co-owner Mehdi Niroomand is a crucial cog in the city’s cultural intermingling, though his baby is a touch removed from the other Irani cafés that have embedded themselves within the city’s definition of soul.

Rather than an intimate space, Shisha spreads itself across a canvas of jungle greenery, a central structure erected from dark wood, and two levels of nooks, crannies, whispers, and memorabilia; in this, it is more aligned to the mountainside Iranian café, as found in droves in Tehran’s hip northern suburb of Darband. Snug in the sounds and spaces of this marriage between an Iranian mountain kebab house and a traditional Irani corner café, I allow my companions’ laughter, the poison-inflected notes from the trumpet player on stage, and my large carpeted divan with its poshti (backrest) to form my narrative.

This is here. This is now. There is nowhere else I’d rather be. This evening is all that matters. It continues to invite a streaming parade of memories, longings, and faded snapshots from earlier in the day. The crescendo rises. The heart swells. The mind erupts with the beauty of all that is, all that has been, and all that’s yet to come.

With the Irani café, I realise, the present will never quite get to separate itself from the past.

~

In compiling this tribute, a few nuggets and some archival anchoring were gleaned from the documentary Café Irani Chai (2013) by Mansoor Showghi Yezdi.

Featured in digital issue KJ99: Travel, Revisited

Siddharth Dasgupta is an Indian writer of poetry and fiction. He has written three books thus far, scattered across prose poetry, fictional desire, and that special somewhere in between. Siddharth’s words have appeared in Kyoto Journal, Poetry at Sangam, Madras Courier, Cha, Coldnoon, Burning House, Entropy, The Bombay Review, Spittoon, and elsewhere. He is currently trying to find a home for three passion projects—two collections of poetry and a novel. You’ll find him on Instagram as @citizen.bliss

Photos by Siddharth Dasgupta