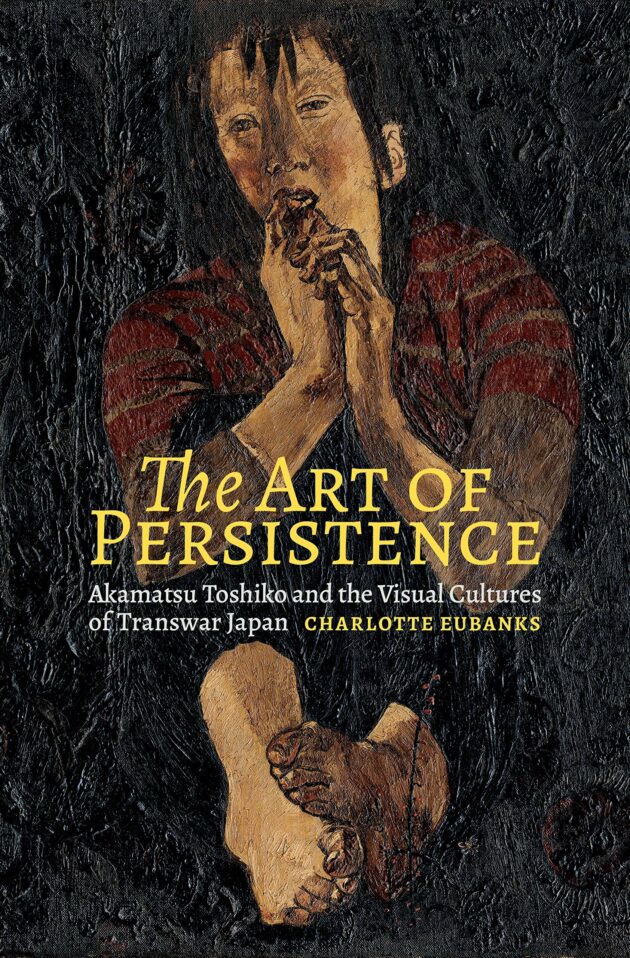

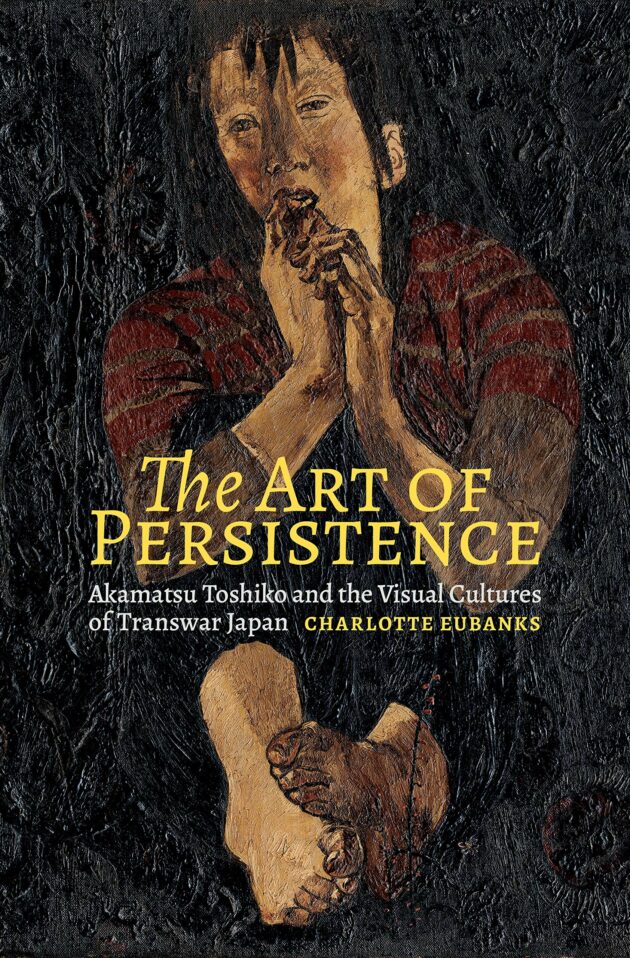

The Art of Persistence: Akamatsu Toshiko and the Visual Cultures of Transwar Japan. Charlotte Eubanks

The Art of Persistence: Akamatsu Toshiko and the Visual Cultures of Transwar Japan. Charlotte Eubanks; University of Hawai’i Press, 336 pp., $ 72.

If you were living under a fascist regime, how willing would you be to compromise your morals in order to survive? If you are reading this, chances are you are among the lucky for whom this question is (and will hopefully remain) purely hypothetical. And yet, from where you are, you probably would not have to travel far in space or time to encounter individuals for whom this question shapes daily reality. Charlotte Eubanks’ book The Art of Persistence is about one such individual: artist and activist Akamatsu Toshiko, also known as Maruki Toshi but referred to as Toshi throughout the book and this review.

Toshi (1901-1995) is perhaps most famous for her anti-war activism and The Hiroshima Panels, a series of artworks on the aftermath of the atomic bombing, both of which she carried out in conjunction with her husband Maruki Iri. Given this legacy, it is all the more salient that in a late interview she called herself “a war criminal.” Toshi explained that during WWII she took commissions for children’s picture books glorifying the war. Though she did so to prevent from starving, she felt that this did not absolve her of her guilt. The Art of Persistence is about this tension between moral imperative and survival, not only during this particular time but throughout the whole of Toshi’s life.

Central to this book is the concept of persistence. Persistence, as I understand Eubanks’ definition of it, is a way of framing agency that accounts for both overwhelming systemic pressure and an individual’s ability to resist it. Put simply, Eubanks says: “Everyone can be held accountable for their choices, but different people have different choices available to them.” Toshi’s persistence, the book shows, is in her continuous negotiation of this “choice spectrum”. Though she participates in and at times even endorses the power structure of her time, she also finds ways to critique it within the bounds of her collaboration. This concept of persistence is refreshing, because it does not judge overly harshly nor does it let anyone off the hook.

Especially remarkable about this book is how it mobilizes what is left unseen and unsaid. In the case of Toshi’s propagandist picture books for example, Eubanks compares her illustrations to those of a contemporary and points out the remarkable differences. Unlike her peer, Toshi eschews images of violence and military weaponry as much as she can. Similarly, excerpts of Toshi’s journals from her time in Micronesia (then part of the Japanese imperial territories) betray between the lines her critical thoughts. She hesitates, interrupts herself and crosses out her words, stopping herself before saying something that might get her in trouble. Eubanks connects these gaps so skillfully that they make a convincing argument and do not feel like mere speculation.

As can be expected from a chronicle of an artist’s life, the book is filled with images. However, do not expect a coffee table book with luscious foldouts and high-quality reproductions. This is, after all, an academic publication. Having said that, sometimes I could not quite follow the image editing choices. The color section for example shows some early paintings by Toshi that the author does not elaborately discuss in her analysis, whilst her most famous works on the atom bombs are printed in black and white and are, for the most part, greatly reduced. This does not do justice to the powerful details and violent red coloring of the Fire panel. This book is an excellent way to learn more about Toshi’s life story, but I would suggest you turn elsewhere for a complete visual representation of her oeuvre.

The Art of Persistence is what Eubanks calls a microhistory. She traces the arc of large historic movements through the life events of an individual and zooms in on crucial moments in which they overlap. For example, Toshi’s time working as a nanny for Japanese diplomats in Russia reveals the dwindling friendship between those countries. And, much later, Toshi’s illustrated reports of war tribunals show her and a nation at large coming to terms with the atrocities of war. This focus is relevant to Eubanks’ argument, of course, but it also results in highly engaging narration of events that might otherwise be described as dry facts.

Toshi was a remarkable artist, activist and intellectual whose voice figured prominently in the post-war discussion. Her artworks and activism even earned her a Nobel Peace Prize nomination. And yet this book also shows that Toshi was complex, flawed, sometimes contradictory: an ordinary human being. This book gave me hope, because it made me realize that persistence does not just concern responsibility in the negative sense. It also speaks of its inverse: our ability to claim micro-agency in the face of adversity and meet the macro-challenges of our times.

MARLIES PEETERS loves words and images in equal, infinite measure. After training and working as a graphic designer, she attended graduate school in Kyoto and Amsterdam. She now works at an educational publisher in her native Netherlands. Noted for her wide-ranging reviews, she also contributed “Art in Crisis,” thoughtful exploration of Kassel’s dokumenta 15, in KJ103.

We regret that this review was incorrectly credited in KJ103.