Visitors to Japan’s main international hub are still greeted by a sign saying ‘Down With Narita Airport’, a giant middle finger waved by diehards from a different era.

Years before we met, I learned about my Japanese father-in-law in a foreign newspaper. A story in the late 1990s reviewed the decades-long fight to shut down Japan’s main international airport. My wife’s dad, Kitahara Koji, led the struggle, which was violent and bitter, waged with bulldozers, truncheons, sickles and Molotov cocktails. Thousands of people had been imprisoned or injured over the years and several—including local activists and policemen—had been killed. Inflamed rhetoric and implacable opposition on both sides were features of the fight: if riot police surrounding Narita International Airport once let down their guard, my father-in-law warned an American reporter, “not one single airplane” would take off. “Yep, that’s dad,” said my wife when I read out the story to her.

I didn’t meet this infamous radical until we moved to Japan in 2000, arriving via… Narita. My wife, though sympathetic to her father’s war with the hated airport, had long ago made peace with it. In any case, avoiding it meant a long detour to Osaka, 400km away, to get in and out of the country. Narita was at that point the world’s sixth-largest hub in passenger traffic. Yet, evidence of the handiwork of my father-in-law and his comrades was immediately apparent: the airport resembled stories I later read about the Green Zone in Baghdad. It was surrounded by high barbed-wire fences and riot police and you couldn’t get in without showing your ID. In the surrounding hillsides, groups of masked, helmeted activists had erected watchtowers, bunkers and wooden fortresses. Homemade rockets were still occasionally lobbed onto the tarmac from local bamboo groves. Bombs were planted in the cars of transport officials.

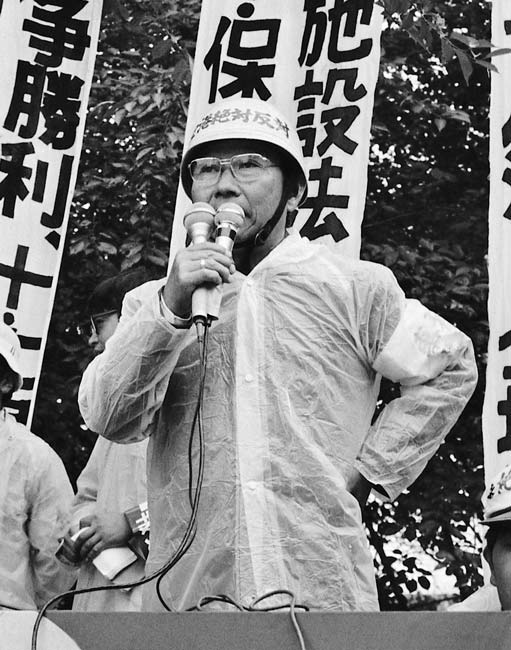

Kitahara was in the mid-seventies by then, wizened and diminutive, with the wheezy, cackling laugh of a lifelong smoker. He lived with his eldest son, his daughter-in-law and their family in a ramshackle house in the hamlet of Sanrizuka, with the smell of jet fuel and the dull roar of airplanes leaving and landing every few minutes. Each takeoff would make the wooden doors of the old house rattle. His business card said he was leader of the Sanrizuka-Shibayama United Opposition League Against the Construction of Narita Airport, or the Hantai Domei. Black-and-white pictures lining the walls showed him rallying groups of farmers and scowling young men, facing off against phalanxes of armed police in riot gear. My wife still bore a scar on her forehead from a police baton charge when she was aged 16. Many of her friends had been similarly beaten, she said. I’d been around radicals in the UK but had never met anyone with such intense hatred for the police.

One photo showed dad clutching a microphone and wearing the sash of a political candidate, his kimono-clad wife standing shyly by his side. He had run for and won a seat in local government but never abandoned the tactics of violent resistance. Members of the Revolutionary Communist League, known as Chukaku-ha, who were famous for launching erratic mortar attacks on establishment targets such as the Kyoto Imperial Palace and visiting American presidents (they once dispatched five homemade rockets at the state guesthouse where Ronald Reagan and other world leaders were gathered) often sat in his cramped living room discussing tactics. The middle-aged Chukaku-ha cadres were soft-spoken and polite as they sipped green tea and explained why their bombs were merely a response to state repression and the tactics of the police, who had turned peaceful farmers, doctors and students into furious revolutionaries.

The origins of the Narita struggle date back to 1966, when the government announced it would build Japan’s new international gateway in Chiba, 60km from the capital—without consulting the 360 mostly impoverished local people who farmed the land around the Sanrizuka and Shibayama hamlets. The plan, with its whiff of official arrogance and highhandedness, became a lightning rod for discontent in the economic miracle years. Many farmers resisted and supporters poured into the area, fueling a conflict that quickly escalated. My wife recalls a youth marred by mass protests and arrests as the authorities tried to quell the resistance and expropriate land. Locals chained themselves to trees and built barricades, traps and tunnels filled with excrement to keep out the bulldozers and police. Tales of the the authorities militarizing the struggle, rounding up all the young males in the area and torturing many, resembled similar tactics in the north of my native Ireland, as did the radicalization it provoked. The leader of the struggle until 1979 (after which Kitahara took over) was Tomura Issaku, a third-generation lay preacher who built a church that would become the center of the resistance. My father-in-law was a school inspector before 1966.

In 1971-—perhaps the peak of the struggle—hundreds of people on both sides were injured in what was called Japan’s bloodiest day of rioting since the Second World War. Three police officers were killed. Rather than pull back or even engage in the normal rituals of public contriteness, my father-in-law blamed the state for their deaths. The fight coincided with the Vietnam War, and indeed shared some of the tactics of the Vietcong (such as tunnel building). Students and activists opposed to the war, and to Japan’s military alliance with the United States, found common cause with the embattled farmers of Sanrizuka. The activists insisted that one reason why the Ikeda Cabinet (1960-1964) had been unable to expand the existing international airport at Haneda, 10km from central Tokyo, to meet Japan’s growing aviation demands was because of the US military, which controlled large chunks of Japan’s airspace since the end of the war. The fact that the airport land was once an estate owned by the Imperial Family added to the sense of injustice: the state giveth and the state taketh away.

As British anthropologist Tom Gill notes, it took over a decade to cajole, bribe and bully enough of the farmers into selling out to build the first runway, which was scheduled to open on 30 March 1978. A few days before, my father-in-law led a group of young militants who tunneled into the airport grounds, raided the control tower and wrecked its equipment and facilities. He was proud of this attack, carried out mostly with steel pipes and baseball bats, which cost him a few months in prison, set back the opening by two months and led to a new round of police repression. Two months later, the New Tokyo International Airport finally began operating, with 13,000 riot police keeping a vast, furious crowd of demonstrators at bay. Firebombs and rocks flew, vehicles burned and hearts hardened. “Our struggle goes on,” Tomura told the press. “No one can guarantee that the airport is safe. No matter how many riot police come and no matter how many laws are passed.”

Some of the literature I read blamed my father-in-law for thereafter pulling the fight away from its mass roots and into the hands of firebrands, militants and full-time activists, though the reality was more complex. The opening of Narita disillusioned many opponents and coincided with the waning of the radicalism that had erupted in 1960 with mass protests against the US-Japan Security Treaty. Along with millions of other rural Japanese, my wife and other young folk around Narita began drifting off to the cities, where their time and energy was quickly consumed by work. But the opposition was still a force. For 23 years, the airport ran on a single overused runway. On my first visit, my father-in-law took me to a sliver of land blocking the construction of a full-length second runway (the original construction plan called for five) and explained that the land had been bought and parceled out to hundreds of supporters around Japan. Narita’s second runway was not completed until 2002 (in time for the Soccer World Cup) but at a truncated 2,180 meters, rather than the 2,500 meters needed for the biggest jetliners. The government did not dare expropriate the land for fear of again inflaming passions.

The man at the center of this melee was unexpectedly sanguine and good-humored. “Nani-ka omoshiroi hanashi aru? “(any good yarns?) he would ask, putting his legs under the low kotatsu and lighting up the first of many Mild Seven cigarettes. He was especially interested in what was happening in Northern Ireland though rarely in my version of it, slowly spooled out in choppy Japanese. “Omoshirokunai na” (boring), he’d conclude, smiling. He laughed often when watching the news on NHK, Japan’s conservative public service broadcaster. “Chigau na,” (that’s wrong), he would chuckle. He was bemused, too, by conservative attempts to whitewash Japan’s war, which as a former crew member of the Imperial Japanese Navy, he had cause to remember. He said the argument that Japan was ‘liberating’ Asia, perpetrated by the right, was “stupid”, recalling how on his wartime visits to Java (president-day Indonesia) the locals were “terrified” of Japanese military uniforms and bowed low to avoid giving offense.

Like most former military men, he rarely discussed the war, at least not while sober—or conscious. My wife told me that as a child, she would hear him screaming out the names of friends in his sleep and from this knew that he had spent several days in the Pacific after his destroyer was sunk, watching them being picked off by sharks. Much later, when I was researching an article on the Battle of Iwo Jima, one of the great slaughterhouses of the Pacific War, I learned that he was aboard a vessel protecting supply ships to the 21,800 troops on the island. All but a handful of these men were killed in the 36-day battle that ensued, and in which 8,000 Americans also died (including nearly one-third of all Marines killed in World War Two). The black sands of Iwo Jima passed into military legend, immortalized in a famous photograph showing a group of exhausted Marines raising the Stars and Stripes on Mount Suribachi on Feb. 23, 1945, and in a 2007 movie by Clint Eastwood. But my father-in-law had no time for mythmaking. For a start, he said, the sculpted actors in Eastwood’s Letters from Iwo Jima bore little resemblance to the tattered and starved military conscripts he saw.

As the ringleader of the oldest social conflict in modern Japanese history, however, my father-in-law had become something of a mythical figure himself. Until poor health forced him to stop, aged 94, he was in heavy demand around the country as an ‘agitator’ or speaker at protests against war, militarism and US bases. Despite his great charm, he was surrounded by a group of questionable acolytes. After years of guerrilla-style violence against the authorities, the left in Japan famously turned on itself in the 1970s and 80s and dissolved into internecine warfare. About 100 activists were killed in deadly sectarian disputes called uchigeba. My father-in-law told me that one day, when he was riding the Shinkansen bullet train, a group of activists from a splinter sect, tried to kidnap him. “That would have been the end,” he said, laughing bitterly. But Chukaku-ha was also notorious for beating and intimidating members of other schisms, which of course alienated anyone not familiar with the obscure doctrinal differences that separated them.

Refusing to surrender after decades of painful sacrifice is, as one commentator noted, a kind of strength, but at some point, the Narita struggle seemed to have become an end in itself. My father-in-law never acknowledged that the fight to stop the airport was lost and talked instead about turning it into a university, in the improbable event that the government conceded defeat. The fight had by then taken an awful toll on all involved. Farmers who had surrendered and taken compensation for their land were shunned. The whole area was a spider’s web of conflicts and alliances. The Kitahara-faction, urging no compromise with the authorities, were pitted against the Atsuta faction, a group of about 50 farmers supported by rival revolutionary groups, including the 4th International and various Maoist splinters. In some cases, old friends who lived side by side fell out, never to make amends.

Kitahara passed away in August 2017, aged 95. It was a remarkable innings for a man who had survived war, prison and treachery, who smoked and drank heavily and weathered considerable stress. Today, five farming households still hold out against the airport, which is one of the world’s busiest. The farmers have been offered huge sums to sell out. Instead, a sign saying ‘Down with Narita Airport’ still greets arrivals, like a giant middle finger waved by diehards from a different era. In January 2021, my father-in-law’s old comrade, Shimizu Takeo (83), leader of Chukaku-ha, reemerged in public after half a century on the run. The police tried to extract him from a scrum of snarling supporters after a meeting in central Tokyo. If nothing else, Narita makes a mockery of the cliche that Japanese culture always strives to harmonize and transform discordance into consensus. Not conceding was the whole point of the struggle.

Graphic photos of Narita protests can be seen here

DAVID MCNEILL is the former Japan correspondent for The Economist and the Chronicle for Higher Education, and a long-term contributor to The Independent and The Irish Times. He teaches journalism and communications at the University of the Sacred Heart in Tokyo and is a coordinator for the electronic journal www.japanfocus.org. An excerpt from his 2012 book Strong in the Rain (co-authored with Lucy Birmingham) appeared in KJ’s post-Fukushima Fresh Currents, edited by Eric Johnston.

This article is excerpted from KJ 102 (Encounters / Transitions), published in Summer 2022.