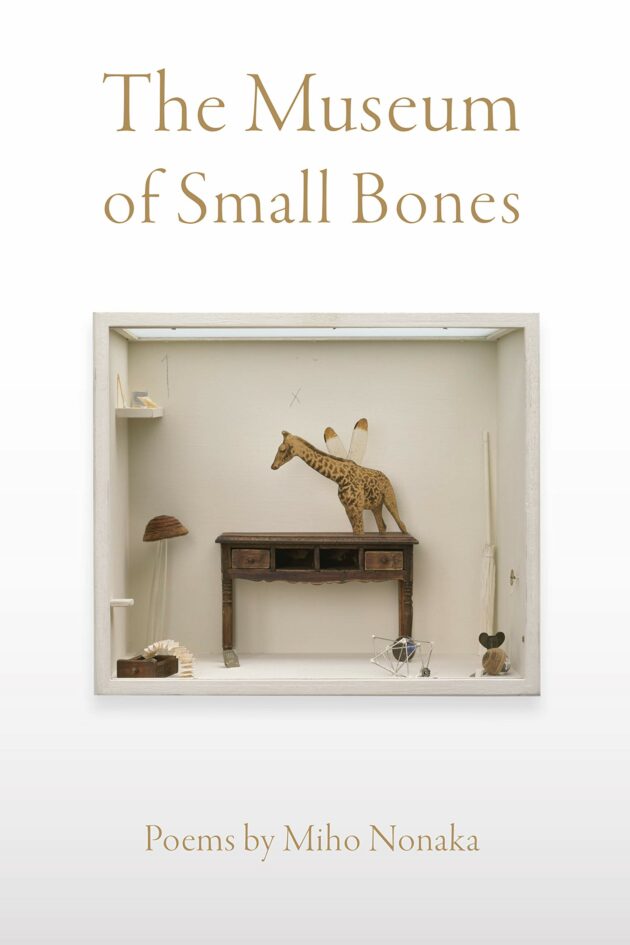

The Museum of Small Bones by Miho Nonaka – reviewed by Alan Botsford

The Museum of Small Bones by Miho Nonaka. Ashland, Ohio: Ashland Poetry Press, 82 pp., ¥2,393 (paper).

In the museum we find relics or remnants or fragments of stories that are not disowned or abandoned; they are contained, enshrined. As readers of Miho Nonaka’s The Museum of Small Bones, we encounter exhibits of a different, ancient ilk. A native of Tokyo, and educated at Harvard and Columbia, among other universities, Nonaka is a bilingual poet/translator who teaches at Wheaton College in Wheaton, Illinois. In this poetry collection, due to her self-confessed restlessness, she pushes forward by small moves, a time-honored tradition. And poetic imagery is her means of locomotion, for natural evolution moves from the literal to the figurative (fundamentalism moves from the figurative to the literal—usually a fatal reversal). In “Bach’s Inventions,” she makes visceral the experience of listening to the piano: “From behind me music starts flowing. / A slight pull on my spine; my fingers / Remember which keys to touch / In what order, and there is no piano.” In “Floating” she writes:

All summer, I longed to become

a jellyfish, so transparent no one

could tell my body from the water

I swim in—a bell-shaped gelatin

with swirling tentacles, drifting

….

As she mysteriously traverses the borders between past and present, “sacred and profane,” “here and elsewhere,” fish and human (mermaid), “birds and branches,” “beginning and end,” economics and aesthetics, America and Japan, “light and dark,” she wants, she says in one poem, “to be / the eye, the point of silence / in the column of turbid air / circulating inward, counterclockwise.” In another poem she adds: “Arms stretched out, / I will walk the tightrope, // never straying from the line / between reality and dream, beauty / and damage. No desire to ever / wake up on either side of the border.”

The locus of her journey—its origin and destination—is the small. The small emerges everywhere, observed and praised: flower “petals recurve like false lashes”; her “skin peels, / leaving a map of islands”; the sound of silkworms gorging on mulberry leaves is likened to “the sound of passing rain”; five grown silkworms together make “the knobby hand of a craftsman”; silkworm cocoons bob “left and right like miniature souls, gradually turning transparent”; and in a visit to the city of Krakow “afternoon stretches/ before you like an untainted mirror.”

The centerpiece of this collection is a brilliant lyric essay entitled “Production of Silk.” Divided into thirty prose poems, it details the process—from raising silkworms to harvesting cocoons to extracting silk to weaving silk clothing—of producing silk, “a sacred project,” she writes (not without irony and circumspection). The sequence also showcases her long family lineage of shokunin (craftsmen) and silk farmers, which allows her to explore not only her personal history but that of Japan in poems about the Man’yoshu, Kawabata Yasunari, and traditional folklore. The overall effect, as she describes a synagogue visit in Prague, is like “being inside interlocking layers of myriad openings to rich interiority.”

The stylistic tensions of her dialogical self, converging east-west construction is less about edifice-building versus improvisation than it is about her willingness to struggle in the difference language and culture makes—that attitude is there in her work. Back and forth between worlds she goes, in “the ritual of switch-backing”. But go too deep and the feud-territory begins, the violence implicit in human relations is unleashed. With descentcomes defense of, or dissent from, the contested realms. This is the way of the world, her poetry acknowledges. She makes no bones (or does she?) of the way things are. This is the remaking of the world, her poetry sings.

“Carpe diem” as the de facto slogan of capitalism may validate private owners who monopolize the means of production for profit, the bottom line. But cutting to the chase obscures the desire needing its say. And have her say Nonaka does: she owns her dreams, memories, obsessions, longings in her own way, fiercely and vividly, pointing to where the way of the small looms large in the imagination.

But though smaller in scale she does not fail to see the bigger picture: “I know we can only love / small things, those which become part of us through / the art of containment.” (This perhaps reveals the poet’s wariness of anything “global.”) When “seize the day” becomes, for the devoted poet-craftsman, ‘cherish the day’ it raises the question—What if it is true, that in love is mirrored the Beloved, for Eternity’s sake, trumping both the time and space of the hollow victory claimed by ‘late capitalism’?

If poetry is dreaming while awake, what is this new reality you enter through dream? Nonaka asks. Her poems “lucid and elusive,” where “all things keep flowing,” are her (at times rapturous) answers.

Alan Botsford is an American poet, teaching in Tokyo.

His books include Mamaist: Learning a New Language, Walt Whitman of Cosmic Folklore, and Mamaist: a Different Sort of Light.