Reinventing a Lost Edo-period Pottery Tradition in Kakunodate, Akita Prefecture

This online special feature is part of a section of KJ 91, on Living Sustainability.

In northern Japan, on the eastern edge of Akita Prefecture’s fertile Senboku plain, snugly nestled against the verdant foothills of the Mahiru mountain range, a family of potters is working to keep the resurrected traditions of their ancestors alive with flair, artistry, and an invigorating dash of modernity. Tucked away in a lush corner of Shiraiwa in Kakunodate, formerly a town in its own right but now part of Senboku City, is their Wahee-gama kiln. In the 1870s, half a dozen kilns were producing distinctive Shiraiwa-yaki pottery wares in this area; today, Wahee-gama proudly stands alone.

Flash back to the autumn of 1771, the eighth year of the Meiwa Era, the 167th year of Tokugawa rule. A potter originally from Sōma named Matsumoto Unshichi has just founded the first Shiraiwa-yaki kiln, following a one-hundred-kilometer journey to find the right place and the right clay to begin a new, northern, ceramics tradition. Additional kilns are soon established by his apprentices, and others later by some of theirs. Deeply connected to the local landscape—born of its very earth and water—the unique Shiraiwa-yaki pottery craft line flourishes, nourished by the region from which it received its name, and by hundreds of local people in supporting roles. Guarded by Mount Shiraiwa and other peaks of the Mahira range, the verdant landscape overflows with natural beauty. Rich with the scent of crisp mountain air and the sound of crystal flowing streams, it bears the unmistakable mark of human input but one respectful of what existed before people walked the earth. Deep woods, shimmering paddies, fertile soil, satoyama, blues, greens: these are Shiraiwa.

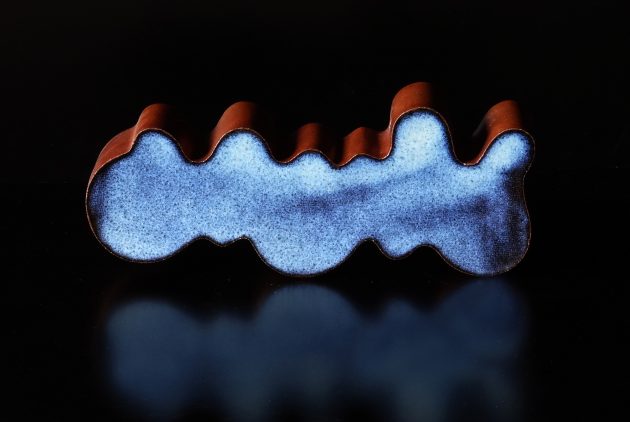

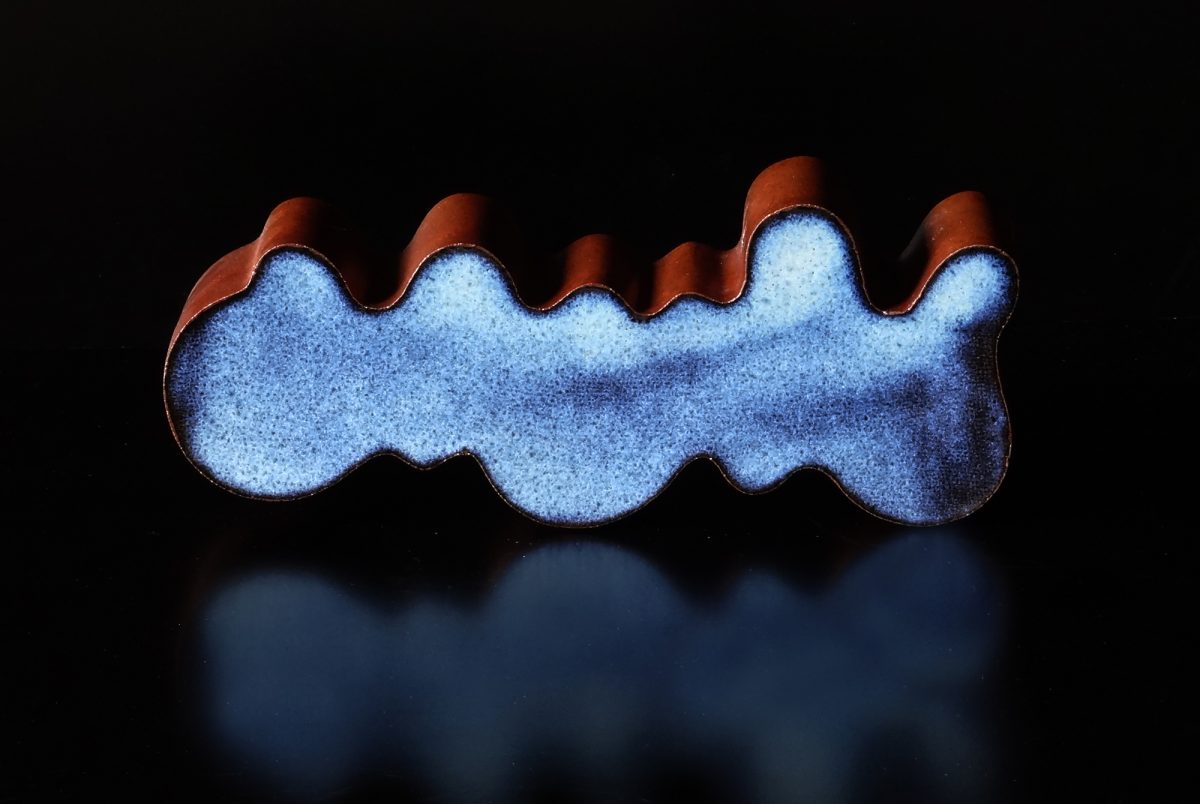

Charming in their austerity, the earlier Shiraiwa-yaki works reflect the landscape that gave birth to them. They are artistic, but also practical—man-made, but natural. Their thick glazes are soft and muted, ranging from whitish-greys to blues, suggesting the icy blizzards of Shiraiwa winters, the melting snows and rushing brooks of spring, and the greens and blues of summer. The fact that the individual pieces sport the unique stamps of their makers testifies to the level of pride that the potters take in their craftwork; it is far more common for pottery wares produced at this time to bear only the kiln’s mark. These two remarkable attributes of the original tradition—artistry and practicality—allow many fine pieces to survive the ages.

As we travel forward through the 19th century, tracing the evolution of the Shiraiwa-yaki ceramics line, we see the kilns lose the support of the local ruling family as the old feudal system collapses, and the potters struggle to compete with ceramic wares flowing in from other parts of the newborn nation beginning in the 1870s. One by one, the kilns become unable to sustain production, and disappear. Then, when it seems things can’t get any worse, the area is pummeled by a massive earthquake in August of 1896.

Within five years of the temblor, the last remaining kiln has closed, and we are left with only memories, archaeological traces, and a legacy of fine pottery pieces scattered across the landscape. Some of the finer specimens wind up in the hands of collectors, and others remain in the area, used for storing pickled plums or coarse salt, for collecting water from wells, for drinking tea or for serving it to the ancestors, or as washbasins. For most local people, they are simply there: practical reminders of something that has been lost… apparently forever.

Fast-forward to the late 1960s. A nationwide folk craft boom is in full swing, and interest in regional ceramics is peaking. Local pride is high, too—fifteen years earlier, eleven pieces of old Shiraiwa-yaki ware and the six former sites of the kilns that made them and their kind were granted important cultural heritage status by Akita Prefecture. Unsurprisingly, someone in Kakunodate is thinking about how to revive the Shiraiwa-yaki pottery tradition as a form of town revitalization (machi-okoshi). That man is Korō Watanabe, a descendant of Wahee Watanabe II, who was adopted into the family from that of Kanzaemon Watanabe, founder of a Shiraiwa-yaki kiln in the early 1850s. An enthusiastic visionary who holds a seat in the town council, Korō is a man of action with a wide vision; he once returned from a jaunt to Tokyo with the first motorized three-wheeler ever seen in Kakunodate. The fact that he had no license to drive the vehicle didn’t matter; he simply thought the town should have one, so he went and got one.

In 1971, Korō’s dream takes a step closer to fruition when his daughter, Sunao, sets out to study art at Iwate University, in Morioka, the capital city of neighboring Iwate Prefecture. Thanks to the 1960s student movements, the art majors enjoy an enviable level of freedom to explore different mediums and move between specializations. However, Sunao does not stray far from her path of choice—she has adopted her father’s dream as her own, and knows exactly what she wants to do.

Yamagata Prefecture native Toshiharu Matsuzaka, on the other hand, moves freely between sections of the art department, flourishing in the relaxed and unstructured environment. One day, he finds himself in the ceramics studio, sitting at a pottery wheel with his hands on a spinning clump of wet clay. Without even thinking about it, he creates a passable vessel with considerable ease. He realizes immediately that pottery suits him, and devotes the remainder of his time at the university to its study. Together with a student from the USA, he decides to build a multi-chambered climbing kiln. Naturally, Sunao lends some of her time to this endeavor, and becomes acquainted with Toshiharu. And somewhere along the way, a connection is formed not only between the two of them but also between Toshiharu and Sunao’s heritage. But this will not take solid form for another six years.

Meanwhile, back in Kakunodate, Sunao’s father uses his political links to the governor of Akita—a fan of Shiraiwa-yaki—to arrange for the prefecture to invite ceramics master Shōji Hamada (1894-1978) to Kakunodate to investigate the local clay for its suitability. Hamada, a former friend and close associate of national folk craft (mingei) movement founder Muneyoshi (Sōetsu) Yanagi (1889-1961) has by this time been serving as head of the Japan Folk Crafts Museum for over ten years. Not only does Hamada give the clay a high evaluation, he gives Korō’s daughter Sunao advice and inspiration, helping to stoke the fire within her—the fire needed to bring the lost pottery tradition of her ancestors back to life.

Following Sunao’s graduation in 1975, she returns to her hometown of Kakunodate to revive the Shiraiwa-yaki tradition, using a kiln especially built for her at her family house. Word quickly spreads, and interest in her quest flares, both locally and across the prefecture. Reporters descend on Shiraiwa, and articles appear in regional newspapers. Soon, she goes nation-wide; in 1977 the Traditional Folk Craft Production Promotion Association releases an 8mm documentary film about Sunao’s mission. It appears that Sunao is perfectly capable of achieving her goal working almost entirely alone, but the key to sustainability lies in the happy union between Sunao and Toshiharu, who marry in 1978. Having also graduated in 1975, Toshiharu studied ceramics at the Dai-yaki kiln in Hanamaki, Iwate Prefecture for three years before teaming up with Sunao in Kakunodate and joining forces to revive the Shiraiwa-yaki tradition. Sunao’s father is so pleased with the couple’s decision to unite and work together, and trusts Toshiharu so much, that he takes the unusual step of legally adopting Toshiharu before the two are wed. Thus, although the Civil Code requires either spouse to take the other’s surname, Toshiharu assumes Sunao’s family name, even before marrying her.

The new enterprise is called Wahee-gama, in honor of Sunao’s 19th century ancestors, and it is located not at Sunao’s family home but in a more secluded spot amidst rice fields at the edge of the foothills where Sunao’s ancestors built their kilns and fired their wares during Shiraiwa-yaki’s golden age. Now, new kilns are needed, but Toshiharu is ready for this, as he has already built one. At his new Shiraiwa home, he outdoes himself by constructing two—a single-chamber kiln inside a shed connected to a workspace behind the shop, and, using 8,000 bricks, a much larger four-chambered climbing kiln in a peak-roofed structure erected with lumber culled by Sunao’s father on his own mountainside property.

Perhaps the biggest hurdle facing Toshiharu and Sunao is rediscovering the long-lost recipe for the special namako-yū (literally, “sea cucumber glaze”) that gives Shiraiwa-yaki ware its characteristic, mysterious, blue sheen. This glaze, which resembles the glistening outer surfaces of many of these echinoderms after being fired, is said to have been imported to Japan in the 16th century by Korean potters brought to Japan by returning members of warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s continental Asia invasion force, after which it spread northward. Today, this silky grey substance is central to many different pottery traditions across the country, including several others in Akita Prefecture—Naraoka-yaki for example. Each variant, however, takes on its own unique appearance after firing. In addition to namako-yū, at least two different white glazes, haku-yū and kohiki, are developed for use at Wahee-gama.

Resurrecting the Shiraiwa-yaki namako-yū begins with careful examinations of old Shiraiwa-yaki pieces belonging to collectors and museums, and continues through tireless experimentation with different mixtures of wood and rice plant ash and other substances. After about two decades of trial and error, they finally succeed, and two types of namako-yū eventually come into steady use at Wahee-gama. But namako-yū is tricky stuff. For one thing, it only melts properly at certain temperatures, and these can only be achieved in a certain part of the smaller Wahee-gama kiln—not at the top or bottom. This means that items coated with namako-yū must be placed in the middle, or “golden zone,” of the kiln. Further complicating matters is the fact that each type of namako-yū has its own optimal melting temperature.

Coating the wares and loading the kiln, and sealing up the entrance, takes five days to a week. On firing day, the kerosene blowers are started early in the morning. About 20 hours and 500 liters of kerosene later they are stopped and the cooling process begins. Once the temperature in the kiln has dropped to about 100 degrees centigrade—which takes around five days—the entrance can be unsealed and the wares carefully removed.

During the firing, the shed that houses the kiln fills up with carbon dioxide. This makes for a rather unpleasant environment, but one that pulls oxygen from the air and also from the wares in the kiln, causing a chemical reaction in both the iron oxide-laden clay of the pieces themselves, and in the iron oxide rich namako-yū covering their surfaces. The magnificent colors of glazed Shiraiwa-yaki wares result from this process—not from pigmentations but from chemical reactions. Managing the firing environment in order to produce the right colors involves striking a delicate balance between firing time and kiln temperature. It also requires sealing off the shed at the right moment to allow the interior environment to become hypoxic. Wares intended to be blue emerge from the kiln with a grayish appearance when the timing is off, even if only slightly.

Today, Sunao and Toshiharu Watanabe work together with their daughter, Aoi, who decided to follow in her parents’ footsteps after graduating from Iwate University and subsequently studying pottery in Kyoto. Aoi, who has incorporated styles and techniques she picked up in Kyoto into her creations, is striving to continue the Shiraiwa-yaki tradition at Wahee-gama. These techniques include putting strips of gold color on certain pieces—a process that requires multiple firings.

Today, Sunao and Toshiharu Watanabe work together with their daughter, Aoi, who decided to follow in her parents’ footsteps after graduating from Iwate University and subsequently studying pottery in Kyoto. Aoi, who has incorporated styles and techniques she picked up in Kyoto into her creations, is striving to continue the Shiraiwa-yaki tradition at Wahee-gama. These techniques include putting strips of gold color on certain pieces—a process that requires multiple firings.

There is also a certain division of labor in the family. Although Toshiharu and Sunao once worked side-by-side, Sunao decided many years ago to step away from the wheel and take a more supportive role, making pieces that don’t require rotation around a fixed axis—a decision relating to the realities of raising children, and an arrangement that continues today. Later, Toshiharu and Aoi shared a workspace attached to the shed that houses the smaller kiln, but he eventually moved into a private work area in the building that houses the climbing kiln. Each, after all, has a unique approach and style.

The brilliant and mesmerizing blue tones and hues that the Watanabe family achieves today with its modern, yet traditional, namako-yū glaze radiate the kaleidoscopic range of malachite, aquamarines, and cerulean blues that surround the family’s home, workspaces, and kilns—evergreen wooded mountainsides, clear water running down from melting snowcaps, cobalt skies reflecting off shimmering rice paddies in spring, and the deep indigo of evening.

The brilliant and mesmerizing blue tones and hues that the Watanabe family achieves today with its modern, yet traditional, namako-yū glaze radiate the kaleidoscopic range of malachite, aquamarines, and cerulean blues that surround the family’s home, workspaces, and kilns—evergreen wooded mountainsides, clear water running down from melting snowcaps, cobalt skies reflecting off shimmering rice paddies in spring, and the deep indigo of evening.

The artistry and quality of the family’s work has helped raise Shiraiwa-yaki to a position of prominence among the range of contemporary pottery traditions that use namako-yū. Although the Watanabe family potters show their works in Tokyo from time to time, the best way to view them is at the kiln. Akita’s relative geographic isolation notwithstanding, it’s well worth a trip to Kakunodate—even if not to experience the town’s two thousand cherry trees and quaint samurai houses, but only to visit Wahee-gama.

Wahee-gama’s homepage: https://waheegama.jimdo.com

Donald C. Wood is a cultural anthropologist and an associate professor in the Department of Medical Education, Akita University Graduate School of Medicine. He thanks the Watanabe family for their time and patience, and also his wife, Akiko, for hers.

Wahee-gama Gallery