Ever since our ancestors gazed skywards or closely observed the wonders of the natural world around them, they saw patterns in cycles and found ways to recall them. Different cultures around the world have developed systems to mark the passage of time, and every calendar reveals something about how the people who created it related to the world around them. The ancient Japanese almanac of 72 micro-seasons provides a map of time that is a fascinating mixture of culture and nature. This traditional calendar marks the progress of the seasons by recording incremental changes in nature, demarcating different periods with names that reflect these seasonal changes. It provided a basis for social and artistic life particularly amongst the urban elite for many centuries.

Haruo Shirane in his book Japan and the Culture of the Four Seasons posits that in Japan since the 8th century, the four seasons were very much a cultural construction, as much as a reflection of the physical world. For the classical Japanese culture of the nobility, centrally important was: “waka, the thirty-one-syllable Japanese classical poem which became a fundamental form of communication among the urban aristocracy and whose seasonal associations influenced almost all major literary, artistic and design-based forms and gestures in Japan. As a result of the ubiquity of waka, flora and fauna as well as the atmospheric conditions of the four seasons became heavily encoded.”1

In Japan’s first poetry anthology, the Man’yoshu, the most often mentioned flower is the hagi (autumnal bush clover). It is characterized by long, arching branches that cascade elegantly and are laden with delicate pink flowers that are easily scattered. In his comments on the most famous work of Japanese literature, the 11th century novel The Tale of Genji, Shirane points out that as the “Shining Prince’s” wife Murasaki lies on her death bed, she compares herself to the dew on the bush clover, which of course is a metaphor for both the physical and mental state of the character in the form of a classical waka poem.

Sandrine Bailly in her book Japan: Season by Season also references Murasaki Shikibu, the aristocratic observer in the Imperial court who authored The Tale of Genji as having written: “It is nature that gives me the most pleasure, the changes through the seasons, the blossoms and leaves of autumn and spring, the shifting patterns of the skies.”2

Bailly concludes that much of Japanese art appreciates the evanescence and beauty of that which is to disappear. With clear influence from Buddhist thought, in Japan this beauty is often described by the term mono-no-aware—the poignant loveliness of the fragile universe. The Japanese imagination eulogizes that which is destined to fade and cherishes what is impermanent. It is in the very nature of fleetingness that we can feel the full impact of this delicate presence.

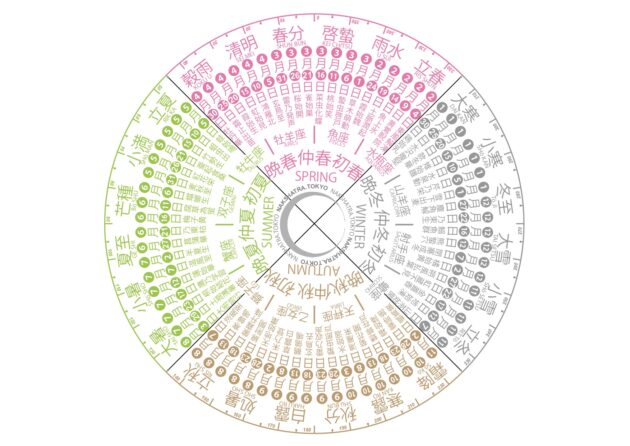

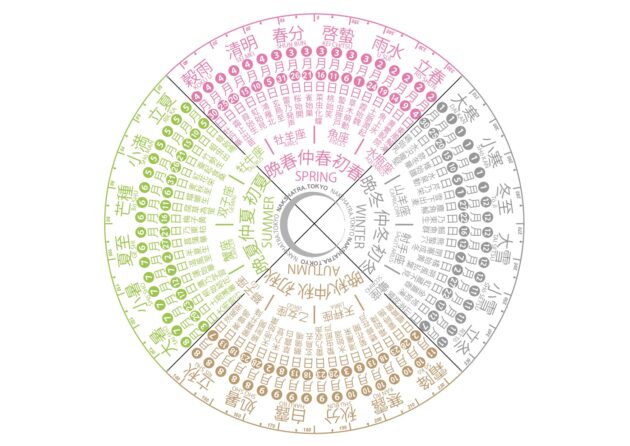

In the ancient Japanese calendar, there are the same four seasons that we are familiar with in the West. However, each season is divided into six parts. Therefore, 24 sekki (major divisions) are created that divide the solar year into equal sections of about fifteen days each. These periods are originally derived from the traditional Chinese lunisolar calendar, a hybrid timekeeping method that considers both the moon’s orbit around the earth and the earth’s 365-day orbit around the sun. Thus, each of the 24 seasonal points matches a particular astronomical event or signifies some other natural phenomenon.

The first seasonal point risshun (beginning of spring), which marks the start of the traditional year, is midway between the winter solstice and the vernal equinox and therefore falls at the beginning of February. The year continues in these fifteen-day intervals until daikan (greater cold) which corresponds to late January in the Gregorian calendar. The 24 divisions are then again split into three for a total of 72 ko (micro-seasons) that last for around 5 days each. Originally introduced to Japan via Korea in the middle of the 6th century, the names that describe each micro-season were based on climatic or natural changes in Northern China, so there were some small discrepancies within the Japanese context. In 1685 the calendar was reconfigured by Shibukawa—official astronomer to the Shogunate government in the Edo period. The calendar that he adapted, using Japanese modifications of Chinese procedures called the kyureki, was used in Japan up until 1873. Then the Meiji government, to modernize Japan, abolished the old calendrical system and adopted the Western solar-based Gregorian calendar. Interestingly, certain groups in Japan, notably, farmers, fishermen and aesthetes continued to use the traditional kyureki alongside the enforced Gregorian calendar.

At the core of each of the four seasons of spring, summer, autumn and winter are the equinoxes and solstices starting from shunbun (vernal equinox), geshi (summer solstice), shubun (autumnal equinox) and toji (winter solstice). The beginnings of each season are also observed in risshun (beginning of spring), rikka (beginning of summer), risshu (beginning of autumn) and ritto (beginning of winter). These markers account for 8 of the 24 seasonal points. The other remaining 16 points are highly influenced by the weather and agricultural elements, such as rain, snow and the progress of the agrarian crop cycle, and feature names including usui (rainwater), keichitsu (insects awaken), shosho (manageable heat) or hakuro (white dew). Likewise, the names for the 72 micro-seasons are very tangible expressions that directly correlate with an actual happening in the natural world at that moment. Of central importance are the natural cycles of plants and animals, and the micro-seasons often have poetic descriptions such as “bamboo shoots start to sprout” or “praying mantises hatch.” Most of the names for the 72 micro-seasons offer visual prompts such as “first peach blossoms” but some are distinctly auditory, such as “”distant thunder” or “frogs start singing.” And still other senses are invoked on this annual cycle, for example “rain moistens the soil” or “warm winds blow.”

But for modern urban Japanese and non-Japanese alike, how might acquaintance with the ancient calendar of the 72 micro-seasons help us to reconnect more closely with nature? Fundamentally, it is an invitation to reconsider our relationship to the passage of time. In breaking up the four seasons into discrete, more manageable chunks, we start to pay more mindful attention to our immediate physical surroundings This more nuanced and evocative way of seeing the natural world encourages us to appreciate our environment more deeply, while realizing that the only reliable constant in our life is change itself.

At a time of unprecedented global uncertainty, our challenge is to find paradigms for sustainable living that foreground peaceful coexistence with our world. The traditional Japanese system of the 72 micro-seasons provides a readily adaptable framework that allows us to recalibrate our year-long journey on this planet. By inviting us to radically slow down and find beauty in the smallest details of our everyday environment, we become more attuned to the rhythms of the natural world. This deep seeing refreshes our soul, gives us hope and builds resilience.

1 Shirane, Haruo, Japan and the Culture of the Four Seasons, Columbia University Press, 2012

2 Bailly Sandrine. Japan: Season by Season, Abrams 2009

This article, adapted and reprinted with kind permission, first appeared in Anthology for the Exhibition Spirit of Shizen, ed. Robert Weis, published by Musée national d’histoire naturelle Luxembourg, 2022.

Mark Hovane has contributed to several recent issues of KJ. Based in Kyoto, he is passionate about Japanese gardens, and curates a notable blog: kyotogardenexperience.com. He also posts regularly on Instagram about Japanese micro-seasonal changes @markhovane

This article was published in KJ104 (Flora & Kyoto), spring 2023.