Editor’s note:

Proletarian literature in Japan, particularly during its period of organized fluorescence before World War II, defies the aesthetic critique that has been used to obscure it. Its authors were concerned (unsurprisingly; any writer would be) with questions of form and style, and didn’t believe that their interest in social realism excused them from confronting these questions as artists, thinkers and craftspeople. The discourse they built around their efforts and amongst themselves reveals an engagement with literature’s textural and component qualities that often surpasses comparable discussions among contemporaries and successors who branded themselves practitioners of ‘pure literature.’ The proletarians wanted to apprehend the very mechanism by which literature implicated itself in a reader’s thoughts, in order to build a corpus that would raise readers’ collective consciousness to literally revolutionary levels.

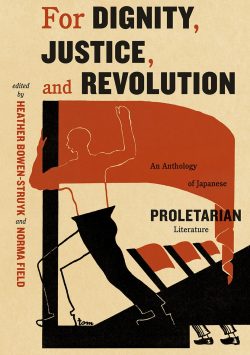

The writers involved in this project never believed that the literary equivalent of a shouted slogan was desirable, although that is the shallow critique that has kept them outside the canon, and, especially in English, out of print. Proof to the contrary returned to print in January, when For Dignity, Justice, and Revolution, Norma Field and Heather Bowen-Struyk’s anthology, was published by the University of Chicago Press. The book offers a representative sample of Japanese proletarian literature’s best critical work and fiction writing, all of it superbly translated and accompanied by insightful, source-rich commentary. It represents an enormous step toward bringing an entire literary movement out of lengthy, ill-deserved neglect. Kyoto Journal is thrilled to share two stories with our readers. ‘Comrade Taguchi’s Sorrow,’ published in KJ 85 with an extended review of the anthology, is a nostalgically-narrated portrait of a young boy’s earliest encounter with the ineffable texture of class boundaries, written by the movement’s best-known writer, Kobayashi Takiji, who was tortured to death by the Special Higher Police in 1933. ‘The Breast,’ written by Miyamoto Yuriko between periods of imprisonment and interrogation, is elegiac in its description of life and livelihood during the movement’s latter days, a period of widespread infiltration and mass arrests. It appears here in its entirety.

From the translator:

By April 1935, Miyamoto Yuriko’s (1899–1951) husband, Miyamoto Kenji, and many of the leaders of the proletarian movement were either imprisoned or released after political recantation. Moreover, whatever was left of the proletarian movement was thoroughly discredited in the media by the scandalous accusation that they were exploiting women by asking them to serve as cover wives (or “housekeepers”) for activist men who had gone underground. Such was the moment Yuriko, who would return to prison in May 1935, seized to publish “The Breast” in the highbrow Central Review. This story offers a richly detailed portrayal of the opportunities but also the dangers facing women— sexism, thugs, spies, the constant threat of arrest, and the housekeeper conundrum. The women in Yuriko’s story persevere in an organized aid movement for supporting strikes and imprisoned comrades, all the while trying to connect with not-yet-striking working people by providing a day care.

The repressive conditions prevailing by 1935 plus Yuriko’s propensity to rewrite make “The Breast” a challengingly layered text. In 1935, Yuriko was still able to use ellipses to avoid objectionable words while inviting readers to fill in the blanks, but in 1937, when she was once again out of prison, she not only filled in the blanks as the new publication laws dictated, but she also rewrote for clarity. Further revisions were made by Yuriko in the immediate postwar period while she was still alive and then by an editor with access to prepublication manuscripts in the politically changed publishing climate after the US occupation ended in 1952. We have used the original 1935 text as a base text, relying on postwar versions to fill in self-censorship when possible–marked with strike-through.

1

A noise . . . something was making a noise. . . . Concentrating all the strength she could muster in her semiconscious state on that thought, Hiroko began to awaken with difficulty from the depths of a deep, dark sleep.

Her eyes opened in the pitch of night, head heavy with sleep, and her prone body suddenly felt like it was spinning. Even in her familiar bedroom, Hiroko had trouble figuring out which way was which.

As she opened her eyes and strained her ears, she could tell it was definitely not coming from a dream. Sometimes a cat would walk on the eaves of the tin roof and make a racket, but this was different. A low muffled sound was coming from somewhere down by the kitchen on the first floor.

Hiroko leapt up silently and reached over for her jacket hanging at the foot of her futon. Sleeping close enough for the sleeves of their splash-patterned, indigo nightgowns to overlap was Tamino, her coworker at the day care. Hiroko felt her way with her feet and accidentally stumbled.

“Wha? . . . Wanna light?”

Tamino slurred her words in her youthful drowsiness.

“Just a minute. . . . I’ll go take a look.”

Hiroko didn’t think it could be a thief, but she was on her guard. The streetcar struggle had begun in September, and this day care participated in support activities, so ever since the veteran Sawazaki Kin was hauled off, plainclothesmen from the precinct were coming by at unexpected times. She’d be no match if they barged in with some sort of pretext like Tried knocking but nobody answered so we thought maybe there was a burglar in here.

There was another reason to be so anxious. There was a dispute with the landlord over back rent. The same Fujii who had recently hung up a sign for Loyalty Association #2, next to the sign for the Hyakusō Digestive Remedies from Ontakesan, had a lot of small properties here, and when it looked like the back rent wouldn’t be paid, he was known to hire thugs to work over the renters. It wasn’t a mere threat, either. His goons would tear up the tatami mats and beat the renters until they were driven out. Fujii had come by four or five days ago. Hair close-cropped and an Inverness cape with a fake otter-fur collar thrown over one shoulder, he sat down and crossed his legs displaying fine satin tabi socks.

“Just ’cuz you’re women don’t mean you can get away with whatever you want, or you’ll be my ruination.—If you’re having a tough time calling it quits, lemme know and I’ll do the quittin’ for ya. Nothing good gonna come from women in Western getup if you ask me.”

His words were menacing but his eyes gleamed lustily at Hiroko’s body, knees tucked under an apron worn over a skirt and loose jacket, even as they also followed the movements of the nonchalant Tamino on the other side of the room. So he’s begun harassing us, thought Hiroko. That bastard! And she threw open the small window of the six-mat room and gazed outside.

Hiroko’s eyes were struck by the moonlight on the dew-moistened tin roofs, spreading low and wide. From high in the sky, the light of the moon, itself invisible, reached all the way to the night-mist-covered field on the other side, making everything glisten delicately. The flimsy scene in the hazy background suddenly faltered before her eyes, as the light of the crooked streetlamp next to the broken bamboo fence dimly illuminated the thick earthen pipe lying nearby. The moonlight melted into the night fog and mingled with the orangey, muddy light of the streetlamp to produce a cheerless effect.

In the night air, Hiroko felt the deep sleep of her neighbors under their low, shabby roofs. Just as she was about to close the shutter, the figure of a man suddenly appeared from under the eave on her side. As if led by his face rather than his feet, the man’s body seemed to angle upward, and turning to the second floor, he gave a wave. From above, Hiroko strained her eyes down at the slender profile and casual clothing that looked chilly in the moonlight.

“Ohh . . .” she cried out, in a voice that said, So it was you. As if that were the signal she was waiting for, Tamino got up and turned on the light. The sudden light on her sleepy round face caused her to scrunch it up even more.

“Mr. Ōtani? . . . What’s he doing here at this time of night?” A healthy knee stuck out of her open kimono as she muttered angrily.

“Go back to sleep before you catch a cold. I’ll wake you if there’s some‑thing.”

From a small three-mat room cluttered with an assortment of old desks in the corner, steep stairs descended into a six-mat room. Feeling her way in the dark, Hiroko lit the ten-watt bulb, passed through the four-and-a-half-mat room with its partition removed, and stepped down in front of the sink. There was no light in the kitchen, to save money. Part of the kitchen shutter was rotting, and Ōtani was making a rattle trying to open it.

“How d’you . . . ?”

“No, no. If you don’t lift this first, it won’t work.”

When the door opened, Ōtani stepped onto the earth floor, looking like he couldn’t wait to get inside.

“Oh, I see, no wonder it’s so much trouble. It’s actually a good precaution, isn’t it?” He blinked his eyes in his innocuous way as he laughed, “Hee, hee, hee.”

“What is it? At this time of night . . .”

“Something’s come up all of a sudden that I need your help for.”

“I thought something was strange, but why didn’t you show yourself sooner?”

“Sorry about that.” Ōtani ducked his head and laughed. “I was taking a leak,” he said in a low voice and stuck his tongue out.

*

Ōtani’s errand was a request to send someone from here to the union meeting in Yanagishima the next morning. They were already unhappy with the forced arbitration, and on top of that, dismissals had been announced. All the depots were once again getting agitated.

“If someone can go meet Yamagishi, that’s the name of the branch chief, at eight o’clock tomorrow, we’ll be all set. I’m sorry it’s so sudden, but—please?”

Her hair in braids, Hiroko crouched on the trapdoor covering the storage area, wearing a jacket given to her that was a bit showy for her age.

“—What a pain.”

She looked up at Ōtani lighting a Bat cigarette.

“—Isn’t there anyone from Kameido who could go? Our Iida is going to Hiroo.”

“I had Usui go ask over there. Apparently, they’ve got the Kinshi Canal area.” Hiroko remained silent for a while.

“—I wonder if he really went. . . .”

With an uncanny smirk on his face, Ōtani met Hiroko’s gaze squarely as he took a long drag on his cigarette, apparently thinking things over.

“Nah, I’m sure he went. . . . He went.” He said it with conviction.

All that was known of Usui Tokio was what he himself had told them, that he used to work with the movement in Kyushu, but nobody knew his background. At some point, he began hanging out at the clinic, and when the union became shorthanded, he started filling in doing secretarial work. He was twenty-four or twenty-five, with a slight build and slumped shoulders.

Hiroko wasn’t the type to take a dislike to people, but she had a bad feeling about him. He would linger after delivering some news, not bothering to chat or play with the children. The way he watched them as they went about their business sent shivers up Hiroko’s back. Instinctively, there was something about him that she couldn’t warm up to, and it distressed her. And there were times when the things he’d say didn’t add up.

One time, when Hiroko brought up her negative impressions of Usui with Ōtani, he sat cross-legged, his down-turned eyes blinking rapidly as usual, his mouth seemingly pouting, listening attentively as he tore an empty cigarette wrapper into small pieces, but he never said anything decisive. Finally, he raised his head to say, “—This should be investigated.”

Since the outbreak of the streetcar struggle, Ōtani had assumed responsibility for the support programs, and his energies were thus diverted, no doubt leaving the matter of the investigation just as it was. When Hiroko raised the question of Usui now, there was a history to it.

Ōtani ground out the cigarette butt that fell on the dirt floor. “Well then, I’m counting on you. Eight o’clock, Yamagishi.”

“. . .” Hiroko made a bewildered gesture, swinging one arm high up overhead and then pulling it with her left hand.

“—Did you know we have a boy with a sty? There are things I need to take care of!”

“Uh, huh—it’ll be over by noon. How about you take care of it after that? Or if it suits you better, go in the evening. The med clinic is open till ten.”

That’s not how Hiroko wanted to do things. She wanted to take care of the child’s sty, which had worsened in the understaffed day care. Then in the evening, as soon as he saw his mother’s face when she came to pick him up, he would say, “Mommy! Rokubō went to the doctor today and the doctor, he washed my eyes out! And it didn’t hurt one bit!” What a difference it made in the warmth a mother felt if she could hear such words straight from her child’s mouth.

Ever since the arrest of Sawazaki and everything else that had been going on, Hiroko thought it was especially important to pay attention to how the mothers felt about the day care, but given how preoccupied Ōtani was with all the movement activities, it was understandable that he hadn’t thought that far. And in any case, the variety of day-to-day problems that arose from current support activities couldn’t be resolved through a casual personal conversation.

“Well, I’ll take care of it somehow.”

Finally, Hiroko placed her hands firmly on her knees and, standing up slowly, said, “—You’ve been unsteady lately. Are you alright?”

“Sure, I’ll be fine. It’s the third Sunday already.—Well, if you’ll excuse me. Sorry to wake you.”

He stepped out energetically then said, “Whoa.”

Straddling the threshold, he turned to Hiroko and said, “Look at this already.”

He showed her his frosty breath in the night air. In the short time since he had arrived, the night mist and the moonlight mingled and silently thickened the cold, making it feel heavy. A ray of light escaped from the house and pierced the cold fog, as Hiroko shivered with one hand on the shutter.

“—Get a letter from Jūkichi?”

“No.”

“The war is making things worse for us.—Please give him my best when you see him.”

“Yes, thank you.”

Hiroko agreed heartily. She listened to the fading sound of Ōtani’s clogs. He was her husband Fukagawa Jūkichi’s dear old friend and now a mentor to her. She locked the door and went back up to the second floor.

2

Rounding the corner of a narrow street, she saw bicycles lined up in a row against the wooden walls on either side. Some of the bicycles had little bundles tied up neatly on the back, while one lone bicycle had an azalea in a small pot carefully fastened with an antique Sanada cord. As she headed up that street littered with leek greens and other debris, she remembered something she had heard about how the well-being of a country’s workers could be determined by their bicycles. Today, she saw before her about twenty bicycles belonging to streetcar workers but not a single one of them had shiny new spokes.

Workers in groups of twos and threes were coming and going from the four glass doors at the entrance. One stood near the door nearly burning himself on his Bat as he took a last drag before finally giving up, stomping out the butt, and going inside. Another draped the hem of his overcoat across the door frame, then in no hurry, lifted one leg at a time to untie his shoes.

Avoiding the shoes at her feet, Hiroko stood on tiptoes and called out, “Excuse me . . . Is Mr. Yamagishi here?”

She directed her voice toward the group gathered around the long table near the end of the entryway. The one wearing a black overcoat with his back to her and his elbows extended turned around to face the brown-overcoat-clad Hiroko standing in the entrance.

“—Hey, is the chief here?” He called out toward the entrance to the stairs. “Yep.”

“Somebody here to see him.”

Someone came down with the thud, thud, thud of heavy heels. Midway, he had to make room in the confined space for three or four people slowly ascending, then after a couple more heavy steps, a plump man appeared, coatless with a stand-up collar and hair parted with pomade.

“Helloo.” His manner was smooth. Hiroko told him she had been sent by Ōtani.

“Well, hello. Thank you for your trouble. Please do come in.”

While Hiroko removed her shoes, Yamagishi stuck his hands in his pockets.

“Will we get to see Ōtani today?” he asked.

“It’s just me. . . .”

“No problem. The ladies are better at getting results—ha, ha, ha.” Yamagishi walked nonchalantly to the foot of the stairs.

“So . . .” He paused in the walkway and rubbed his chin. “What order should we go in?”

Hiroko had a funny feeling like they were deciding who would go first at a lecture. “As you please, I’m fine either way—”

“Well then, may I go ahead?” He spoke quickly and led the way to the second floor.

Up the steep stairs, three rooms of various sizes had been opened up to form a large space. Pausing by the wall, Hiroko saw, straight ahead, posters printed with dark black ink hanging from the beam. “Absolutely oppose the firing of 130 people!” “Oppose bus transfer tickets! Demand support for conductors!” Lined up next to the one on forced arbitration was “1,213,270 yen—absolutely oppose cutting personnel expenses!!” There was an assortment of such posters.

In the two rooms to the left, the morning sun shone through a waist-high window opened wide. The beautiful though not-yet warm morning sun shone on the backs of several people huddled in the window frame, one of whom kept wiggling his big toe in his sock as he explained something. From where she stood, the people were backlit and the cloudless sky spread out behind them with two rows of four vent shafts on a slate roof spinning in unison.

In a corner holding the only two chairs in the space, one person straddled the seat facing this way, leaning on the shabby bentwood back with his chin in his hands, while another sat letting one knee jiggle nervously.

One man sat on the tatami mat, head down as he hugged his knees. Another sat cross-legged, rocking his whole body with his arms between his legs.—

Hiroko felt complicated undercurrents circulating in the room. Beneath the air of well-worn familiarity and the pervasive feeling that nothing could surprise them, she could sense an agitation whose direction was as yet undecided, an anticipation that could not yet find its way to the lips. Hiroko could see it, for example, in the alert look on the face of the thirty-something straddling the seat and jiggling his knee.

Finally a tall employee with a compress wrapped around his throat went up to the small desk at the front. He looked at his watch and wound it, then he sat at the desk and said something to the vacant-looking middle-aged man seated cross-legged on the floor with his head in his hands.

“Well, we’re ready to start.”

One of the men straddling a chair lowered himself to the tatami mat and crossed his legs and the other stayed as he was.

“Close it, will ya? It’s cold.”

The man next to the window put up the collar on his overcoat.

“I now open the meeting of unit 5 of the union.”

The one wearing the old-mannish compress on his neck was evidently the chair, and he conducted the meeting.

“In the afternoon of the twenty-sixth, at a meeting between Chairman Kawano and Ōishi and Satō, our strong objections to the unjust termination of 127 employees were raised but summarily rejected, and the facts of the case were immediately broadcast. Today, we’re here to report on developments since then and decide on the stance to be adopted by our unit 5, but first, labor aid has sent somebody here today, so I think I’d like to start there.”

At which point, an employee with the air of a family man seated cross-legged next to Hiroko raised his voice but not his head and yelled out “No objections!” in an exaggerated manner.

“—Well, then. . . . Please go ahead.”

Hiroko sat up straight and was about to speak, when she was told, “Please come up here.”

Hiroko walked to the front as a slight rush of blood went to her face. “No objections!” someone yelled at the back. There was laughter.

Not at all perturbed, Hiroko took in the atmosphere of the room and began speaking in clear, unadorned language about how much the current struggle was attracting the interest of even the wives of ordinary workers, giving real examples, like what Hideko’s mother, who worked at Shōki Hosiery, had to say. Then, she explained how just that morning, they established a family aid organization in Hiroo and opened a mobile day care.

“Yesterday, Mr. Ōe committed suicide by jumping in front of the train near Keio University Station, and this is truly a shame. According to the newspaper, he was a drunk, but the people of Hiroo tell a different story. They say that his wife had been ill so he missed a lot of work, which served as a pretext to fire him and led him down this road. If we were stronger, if we had our own hospitals, then Mr. Ōe wouldn’t have had to lose his job because of his ailing wife. When I think of how he didn’t need to commit suicide, it seems like such a shame.”

“No objections!”

“That’s right!”

There was strong applause. Unknown to her, Hiroko’s face burned with a beautiful expression of concentration.

“Please, everyone, give it your all,” she said. “We are making preparations. Please stay strong so that it won’t come to nothing.”

There was no hint of the earlier heckling; instead sincere applause continued for some time.

“—Well then, we’ll have some reports next.”

*

Responding to popular demand, branch chief Yamagishi put one hand in his pants pocket and launched out in an oratorical tone.

“Unworthy though I am, as branch chief I bear responsibility to you all, and I declare that I am resolved to struggle till the end on the front lines. Next, I want to move to an open group discussion of specific methods in the immediate struggle.”

From the moment he said this, the room became visibly tense.

“Anyone with questions or opinions on the chief’s proposal, please speak.”

“. . .”

“Mr. Chair!”

At this time, a young employee across from where Hiroko was seated against the wall raised his hand, elbow out to the side.

“I want to share the decision of the number 3 squad.”

“Please go ahead.”

“We at the number 3 squad held a meeting this morning, and anticipating that our demands would be summarily refused, we moved to strike and elected a strike committee.”

“. . .”

A slight commotion arose in the room. A couple days earlier, they had received orders from headquarters to not compromise and prepare to strike if the 127 employees were fired. Yamagishi lit a cigarette and made a show of frowning at the smoke in his eyes.—

“Hold on a minute. . . . I have a question—” The silence of the group, thrust into indecision, was broken by a single slow-sounding voice. “That decision made by the number 3 squad—What does it mean?—Does it mean that even if all the lines don’t join, you’ll go it alone?”

“That’s how the people in the number 3 squad feel,” the young employee answered quickly and closed his mouth.

“If that’s the way it is . . .” The one who had slowly broken the silence before now suddenly sat up straight and raised his voice provocatively, “I’m against it. I’m against the proposal.” He hiked up his shoulders under his overcoat like none of this was worth his time.

“No objections!”

Another voice followed. “Me, too. I’m against it. Look at what’s going on here. If this gets yanked up by the roots, then we’re all goners.”

Hiroko was paying attention with every fiber of her body. As if in response to each other, came cries:

“Mr. Chair!”

“Mr. Cha-air!”

Two voices broke out in competition, and the high-pitched voice forcibly overcame the other. “No, I don’t think that’s right,” it protested strongly. “I think you can understand if you just look at what happened with the strike in Hiroo in February. A partial strike can take place, and in fact, conditions are ripe for this to lead to a strike on all the lines. If that wasn’t the case, why do you think headquarters would be issuing these commands?”

“Mr. Chair!”

An elderly man with many fountain pens and mechanical pencils in his breast pocket spoke in a calm voice. “I’m in squad number 1. This is just my personal opinion . . . but as far as a strike goes, I absolutely agree!”

“However . . .” He cleverly drew everyone’s attention to himself. “However, if all the lines aren’t going to rise up together, then I’m absolutely opposed.”

Hiroko felt something hot rising up in her chest and she bit her lip. How skillfully they were causing it all to fall apart. But she was just a visitor with no right to speak, and that pained her.

Stirred up by the slick use of words, someone started to clap.

“It would be infantile to strike or whatnot without thinking though the different power relations. You think we can do that right here right now?!”

“Mr. Chair!”

Again, the high-pitched voice asserted itself. “Power relations are relative, so if we’d tried to make a push before the forced arbitration currently going on, no reason we couldn’t have. But we were told to leave things up to the no-good reps who used to be on the other side, and they just dodged our demands.”

“Exactly right!” “No objections.”

“Isn’t there talk that this time around, headquarters has presented a list with names of people to be fired?”

“That’s no laughing matter! Tsk!”

From around the time of the general assembly, more than sixty employees said to have tendencies had been removed from the different depots including those on the labor aid committee. Looking at it now, it was clear to see what their plan had been. Hiroko was bitter.

A strike by all the lines or none. Anything less than a united strike by all the lines would be meaningless—this was, in effect, the defeatist idea propagated by the Tokyo Transit Labor Union that had, from the beginning of this dispute, infiltrated the hearts of the workers through superficial . . . . . . interpretations of orders and policies. As the situation became complicated, such ideas were likely to appear everywhere. As far as support for the streetcar dispute was concerned, when the Kameido day care made a mistake by overdoing it and scaring the parents, some people thought that all struggle support should be canceled, while others thought the cause was worth crushing a day care if that was what it cost. It was Ōtani who explained why both of these ideas were wrong.

Among the rank and file at the workplace, there wasn’t the strength left among those who should organize and stand at the head to get to the bottom of this dickering and lead them on the path to proper struggle. Even Hiroko could see as much.

As the room became smokier, confusion ensued with preposterous opinions and questions following one after another.

There should absolutely be a strike. However, it should only be done if the leadership could guarantee its success 100 percent.

Or, someone would say with great purpose, “I have a question for the branch chief.” What, he wanted to know, was national socialism? At first, Hiroko thought the question was an invitation for the chief to put forth a proper explanation of the pros and cons of national socialism for workers, but no, Yamagishi ended the discussion with a vague, un-class-conscious response.

Then, “Mr. Chair!”

A brand-new idea was introduced. Tokyo Transit was proposing the slogan “Down with fascism,” but one man said he was opposed to that slogan. Tokyo Transit was supposed to look out for the economic interest of workers, not get involved in political parties and politics. Therefore, “Until all that gets clarified, I don’t aim to pay no union fees.”

“What a lot of nerve!”

“Who d’ya think you are, Shimoda!” “Get outta here, ya fascist peddler!” “Mr. Chair! Order in the room!”

“Silence, please. Everybody, please speak in turn.”

All the while, branch chief Yamagishi sat with one hand in his pocket, the other supporting his chin on the small desk, heavy eyelids closed, making it hard to tell if he was sleeping or not, in any case, surrendering to the chaos.

The pandemonium continued, and when it had sucked all the energy out of the room, the chair raised his pale face.

“Well, that’s all the time we have.”

He called for a resolution. Yanagishima depot would walk off immediately if someplace decided to go on strike. That was the curious resolution passed.

3

Hiroko left the office through the back door, feeling worse and worse as she walked alone on the cinder-covered path alongside a tenement.

It was a complicated feeling. Tokyo Transit was not doing anything except standing in the way of the workers. Despite this fact, she herself had ended up simply talking about support before the debate began. She sensed her mistake now. If she had only spoken later, when the atmosphere in the room became so disjointed and confused, she might have provided a bracing stimulus. Yamagishi saw it all coming and acted accordingly. Yamagishi had used his skills as the union petty bureaucrat that he was and managed to avert this, which was perfectly predictable.

As she emerged onto a wide, reconstructed boulevard, there was a newly built concrete bridge. It was closed to traffic in one direction, with piles of cement barrels, rods, and square lanterns inset with red glass. On top of a sunny pedestrian walkway, a seven-year-old boy in a brown jacket and rub‑ ber boots was playing tops with another crew-cut boy his age in a splash-patterned kimono and rubber boots. The two boys stared intently at two small iron tops gleaming in the sun. Phst! Phst! Spittle was flying as each gave his top his best, energetically spinning the ropes with all his might, never taking his eyes off for a second. Their utter devotion caught Hiroko’s attention.

Relaxing her pace, Hiroko looked at her watch and then, slowing down even more, she opened her handbag and looked into a compartment. Inside was the visitation permit she had secured from the court about a week earlier. It was folded in quarters with the edges already beginning to fray. Hiroko shut her change purse with assorted five-sen and ten-sen coins, cocked her head to the side, and looked at her watch once again, but this time, her plain black shoes made a beeline for the bus stop.

Jūkichi was transferred to Ichigaya Prison almost six months ago. The police had had him for ten months. Even Hiroko had been detained for about six months, so she hadn’t been able to see him then, nor was she able to see him when she was released. When she first learned that he had been moved to presentencing detention, she went to the court, and they told her:

“He won’t even confirm his own name with the police, so you could say we don’t know whether we’ve got a ‘Fukagawa Jūkichi’ or not. Still, given the evidence, we do know we’ve got him, so we’ll grant permission.”

Jūkichi had been sent with blank forms.

The train turning back from the end of the line was empty. There were few passengers except for an old man sitting on the sunny side, elbow resting on a large square package wrapped in white cotton, digging out earwax with the long nail of his pinky finger. The elderly conductor leaned casually on the side of the door near the front, got out his notebook, and periodically licked the lead of his stubby pencil while pondering something. It wasn’t unusual for those who had been with the train for a long time to play the market.

Watching the face of the old man immersed in his own world despite the conductor’s pouch he carried, Hiroko recalled a passage in a letter she received from Jūkichi with countless implications. Jūkichi had written that it was certain that a precondition for health was the stability that comes from being mentally steadfast, and he described the health measures he was taking on the inside. Outside, too, there must be many unusual goings-on. The gears of history didn’t transmit all their subtle noises to where he was, but on that point, there was no cause for concern. That was what he had written.

No cause for concern.—As Hiroko thought about the constrained expression and all it implied, she in no way flattered herself that this was just for her sake.

She overshot Ueno Station, but didn’t realize her mistake for some time. When she finally looked up, she was surprised to notice that while she wasn’t paying attention the passengers had completely changed in appearance, skin luster, even in their skeletal structure.

Hiroko was jostled as she traveled in a wide arc from the east to the west of greater Tokyo, but as the train neared the Yamanote area, the appearance of the men and women getting on and off contrasted more and more with the residents east of the castle, where the toxic smoke stymied the growth of green trees.—Hiroko got off the train at Shinjuku 1-chōme.

She came out onto a street lined with tall signs advertising prison-visit supply shops. She strolled along for some time when, suddenly, right before her was the gate of the prison against the expansive sky. Outside the gate, there was a bench that looked like it belonged in some small country train station somewhere, and it made the height and width of the concrete wall behind it seem all the more conspicuous. As if they had been tossed up by a gust of wind, two planks serving as a roof for the bench were tilted high, leaving the seat of the bench to get soaked on a rainy day.

As Hiroko looked at the brilliance of the sky whose blue could be felt more palpably here than in other parts of the city up above the hushed monotony of the thick concrete walls, her chest felt constricted and she realized that here there were two horizon lines. And she felt the unnaturalness of it.

Hiroko entered, stepping on the gravel, selected, no doubt, for the way its crunch echoed. Gravel was spread everywhere.

Men and women were separated in the barracks-like waiting room. As she opened the glass door, her nose was assailed by the acrid stench of charcoal briquettes. It was mostly empty. One woman, apparently a former barmaid clad in a wool-knit cloak-like jacket with a fallen chignon bun and plastic combs, sat cross-legged with hands in pockets, walleyed and mouth ajar. There were another four or five people besides her.

From noon to one o’clock was break time. It was just fifteen minutes until Hiroko’s appointment at one o’clock.

She submitted the penny candy and soy-boiled seaweed she bought at the store as a care package and went out to stand in the sun for a while. There were plantings of pines and some other trees. On the far left was the interview room, but the first time Hiroko had visited, she had mistakenly gone there thinking it was a toilet. That was what it looked like.

Outside the gate, tires sounded on the gravel and then the door opened and a car came through. Three or four men were saluted as they got out and went into another building.

Watching that scene from where she stood, Hiroko remembered something she’d heard about how Jūkichi had to crawl up the stone stairs of the entryway when he first arrived.1

She got worried and looked at her watch. Not even five minutes had gone by. Waiting was long like that, but when the time came and she saw his face and started to say something, it would seem like they had hardly exchanged any words at all before the window announcing time’s up would close. These visits were quite draining, what with the anticipation built up over the long wait entangled with the acute tension of the cramped, short visit itself. The instant the window opened, Jūkichi would smile hello, gesturing slowly as if rubbing his shoulders. When the window shut abruptly, it would cut off the end of his “Well, then, take care.” But the inflection of his voice would stay with her until she could visit again the next month, and she recalled with fresh emotion the subtle expression in Jūkichi’s eyes and around his mouth.

A small, cracked mirror was stuck inside her handbag. Hiroko took out a handkerchief and wiped away the dust that had accumulated on her face since the morning, then took a new section of the handkerchief, rounded it and rubbed above her cheeks. A little color appeared.

The loud speaker in the wall of the waiting room seemed to have been switched on and began to buzz. When she opened the glass and peeked inside, the women, straining to catch the static-filled announcements, buried their chins even further into their collars and adjusted their sleeves.

“Um . . . Sorry to keep you waiting. Um . . . number twenty-eight, number twenty-eight go to number six. Number six. Um . . . Next is number thirty.” At the sound of the voice, a woman near forty who looked to be the wife of a thought criminal rose from a folding stool covered with a straw mat, draped her shawl over one arm, and forlornly looked up at the black horn.

“Um . . . number thirty, the person you were here to meet has been sent to another prison.”

Hindered by the grating buzz, even Hiroko’s ears heard “a mother prison” instead of “another prison.” The gentle-seeming woman who appeared to be the prisoner’s wife involuntarily took a step forward with a “What?”

And turning to the speaker, she tilted her head in a feminine way to listen again. With an abrupt click, though, the switch was turned off, and the woman was left standing speechless in a pose of surprised confusion, and just like a male kabuki actor performing a woman at a complete loss, she turned toward Hiroko, dragging her feet and letting her kimono hem split open.

Hiroko was overwhelmed with sympathy.

“It sounds like he has been moved to another prison. Try inquiring at the office—the door is right over there.”

She pointed to the painted main door of a two-story building.

After waiting for more than an hour, Hiroko was finally able to talk with Jūkichi for a couple of minutes.

Without realizing it, Hiroko pushed her chest up against the bars to the point where it hurt. She asked Jūkichi about his health, told him about his mother who lay paralyzed, then apologized sincerely that, as always, the books he requested had not come in. Eking out an independent life amid the financially strapped day care left her without even the resources to walk to borrow books. And those occasions when she might have a bit of money, she lacked the time. Taking advantage of the times when she had both, she managed to get just a fraction of the minimum he needed. As a rule, the people who didn’t mind lending books never had the kind that Hiroko wanted. Those who were likely to have them didn’t, in general, like to lend them. Even in such matters, things were more frustrating than a person might think.

Having been brought out suddenly, Jūkichi stood suspended in space, forced to recall everything at once. Furrowing his brows and shifting his weight from one foot to the other, looking unwell, he managed to give the titles of some books.

“But, Hiroko, you have to think of your situation, too, so don’t go to too much trouble for me. Even when there is nothing for us to read, we are still thinking about things in a way that is productive.”

Hiroko wasn’t especially eager to broadcast her feelings, but she spoke slowly: “This morning I went to Yanagishima, and look how late it’s gotten. . . . You must feel neglected, but please know that it’s not because I’m not doing anything,” she said. She closed her lips but smiled with her eyes.

Jūkichi muttered, “Hmm . . .”

He glanced at the guard who stood, cord in hand, ready to close the door, then transferred his gaze directly to Hiroko’s face, and drawing himself up like a man who has just tightened his belt, he said forcefully, “Set aside a little money if you can, just in case you ever get sick or something, so you don’t suddenly find yourself in trouble.”

Thinking of the way they lived, Hiroko tried to grasp the content of Jūkichi’s words in all their fullness. He was not just talking about money.

Leaving the cold place that resembled a communal toilet, she headed for the gate across the sunny courtyard and found herself thinking that she was walking across the gravel just like all the other women who had come out for visitation. She was so glad she got to see him, but “glad” didn’t begin to describe the feelings she carried in her heart.

When she exited the gate, she saw in the clearing immediately before her a baby monkey wearing a padded kimono vest. Standing and squatting, a group had formed a circle around it, including two or three men in suits and a security guard with a pistol. This strange little monkey was different from the ones trained by showmen. With black ears standing straight up on both sides of its head and a blue-tinged tail dragging on the sun-warmed gravel, it moved its wrinkly face up and down, eyes darting restlessly as it ate something.

“When you see them like this, they’re quite cute. Ha, ha, ha . . .”

It was a shabby little monkey. These were men who paid no attention to the people coming and going but could lavish affection on a monkey. Feeling the coarseness that came with their occupation, Hiroko walked away.

4

One afternoon several days later, Hiroko was folding diapers in the entryway while the two babies napped upstairs. From a distance, Hiroko heard the sound of Tamino in skirt and clogs approaching. When Tamino came up next to the pump shared with the sewerage pipe shop, she said, “Wait, what happened to that sign? It’s flipped over.”

She spoke loudly. Jiro, who was playing in the garden, said, “Miss Iida, whatcha mean? What sign got flipped over?”

Five-year-old Sodeko and Hideko, even toddling Gen, gathered around Tamino.

“Next to the bridge, there used to be a white triangular thing, right? It’s lying in the bottom of the ditch now.”

They stood in a bunch near the entrance. Hiroko, sounding suspicious, said, “But—it wasn’t even near the edge.” As she spoke, she stepped down onto the dirt floor. The sign with Hebikubo Proletarian Day Care painted in black on a white background had been erected on the side with all the sewer pipes, about six feet away from the ditch, where it would catch the attention of pedestrians.

“Look!—Who could’ve done this? It’s so mean.”

The sign had been dumped headfirst into the muddy, withered grass in the ditch.

“It was fine this morning, wasn’t it?” “Yeah, I didn’t notice anything when I left.”

The children lined up along the wooden bridge, eyes open wide with surprise. Sodeko, who had been taken by the hand by Tamino, suddenly shook her short bob and yelled, “Hey—it’s my daddy who made that!”

“Yes, that’s right. Son of a gun.” Standing next to the pipes, Hiroko gingerly lowered one leg, then using the roots of the withered grasses as a foothold, keeping her center of gravity as low as possible, reached out her hands. Even so, the upended sign was still two feet away.

“Be careful! It’d be awful if you fell in, too.” “I’m okay.”

The young man from the cleaner’s across the street stopped his bicycle and watched with interest the ruckus being raised by the women and children. “—Um, that isn’t going to work unless you got some rope.”

Clapping the mud off of her hands, Hiroko gave up.

“When Sodeko’s father arrives, we’ll ask him to get it out for us.”

As they retraced their steps, Jiro kept asking,“Who did this, huh? Why’d they dump it in the ditch anyway?”

Jaw set and flushed with anger, Tamino took large strides, Sodeko’s hand in hers. “It’s gotta be the handiwork of Fujii’s thugs.—They’re just looking for trouble, the whole lousy bunch of ’em.”

It was clear this was not just the antics of a drunkard.

“And you can be sure it’s a no-good spy that put ’em up to messing with the pump, too.”

Two days earlier, Ogura Tokiko, a graduate of a women’s college who was temporarily helping them, had been washing diapers at the well. At the sound of the water running, the glass door to the kitchen of the sewerage pipe shop opened, and it wasn’t the wife but the owner, Seisuke, who popped out his head to say: “Hey, you keep usin’ water like that and we’ll all be in trouble. It ain’t just one household usin’ this, ya know. Won’t even be able to rinse our rice, we won’t.”

“I’m very sorry.”

As she walked over to the clothesline, Tokiko’s glance had met Hiroko’s through the window of the four-and-a-half-mat room. A look passed over Tokiko’s face, the defensive look of a person unaccustomed to being treated harshly, and then she laughed. Hiroko understood exactly how she felt and, for that reason, had said nothing.

Lips pressed tightly together and deep in thought, Hiroko led the way into the house.

“Well, thank you for your work today. How did it go?”

Seated on the floor with legs folded back alongside, Tamino reached into the pocket of her skirt, pulled out a small brown paper envelope, and one at a time laid out three nickel coins and ten or eleven copper coins.

“Auntie Yoda was holding out, saying she already gave, you know.—And this is all she gave!”

An envelope was passed around in the name of the day care to collect funds for the streetcar dispute.

“They don’t feel directly connected, so that makes a big difference. And they seem to think it’s foolish to risk a crackdown when there’s no way to know who’s gonna win.”

Among the streetcar workers, there were a number of worker-farmer aid groups. When Hebikubo Day Care approached them with a request to buy cribs, a group in Yanagishima took charge and raised the funds. That was the money that provided the three wicker cribs in the nursery. That was how the mothers and fathers using the day care who worked at Fujita Industries, Inoue Tanning, Shōki Hosiery, or Kōjō Printing had come to be connected with the streetcar workers. There was something of a sense of fellow-worker loyalty, and one time during a collection, they raised close to three yen. But the moms didn’t make any headway with such activities in their own workplaces. Ohana from Tsunaya could only collect twenty sen from the neighbors in her tenement she had invited to a sale by the consumer union.

These were the kinds of experiences that Hiroko talked about with a group that had been meeting at her place for the past couple of months. When they got into a debate over a piece they had read for that day, Ōtani proposed, “I feel like I keep repeating myself, but especially with these kinds of problems, I think we have to base our studies on our concrete experiences.” So they also talked about what was going on at Hebikubo.

At Kameido, a special mother-father committee was formed to start up aid activities. A young person from . . . . came and earnestly explained what worker solidarity was about. He spoke fervently about how, just at the moment when the crisis of . . . . was approaching, what an important connection they all had to the . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . of the streetcar dispute. The parents were moved as they listened attentively, and they contributed substantially on the spot. However, an odd thing happened as a consequence. One child, then another, stopped coming to the day care until, finally, five children from one tenement no longer came.

“It was bad to lay it all out from beginning to end in one session.” A day care worker with long eyelashes offered this in self-criticism.

“It seems that it was because what was laid out in the talk was so persuasive that they felt that once they got involved in the dispute, they wouldn’t be able to refuse. Then they’d have to worry about their own necks.”

“That so, huh. Because the talk was so persuasive. You don’t say.” Ōtani grumbled “huh” one more time, then asked, “So, just like that, they really stopped sending their children?”

“That’s right. They’re not coming.”

At Hebikubo, too, there were two or three parents who had stopped sending their children after the arrest of Sawazaki Kin. One of them worked at Inoue Tanning, with Mrs. Yoda, who said she’d heard it like this:

“Well, ya know even though we live like this, we still have some social connections, and from time to time we’re obliged to call on people who live in kind of a fancy house. Well, one time I brought my little Ikubō, and would you believe it, right in front of everybody he goes and says in a loud voice, ‘Ma! These people are bourgeois, ain’t they? So they’re the enemy.’ I turned bright red, I tell you.”

Hiroko smiled wryly. But that story didn’t represent the current reality. It was a bias that appeared in the early days, just after they had unified around. . . . activity.

*

Hiroko heard the sound of a baby fretting and went up to the second floor.

Ohana’s Chiibo scrunched up a face so small that it was hard to tell if he had grown at all in his ten months, and he whimpered as he shook his head as if he was having a hard time sleeping. Hiroko changed his diaper. His bowels were loose. A doctor had told them to offer the baby goat’s milk in addition to breast milk, so Ohana gave him some and then dropped him off at the day care when she was out working many hours.

As Hiroko changed Taabō’s diaper, she heard from beneath the window, “Alright?! This is our fact’ry!”

It was Sodeko’s high-pitched, determined voice. As Hiroko dragged Chiibo’s crib over to where he could get some sun, she looked down at the clearing in front and saw that Sodeko was in the corner grasping the cutoff rope from a broken swing and waving it as though she were reeling something in. Jiro, in a jacket that had been lengthened piecemeal with blue and brown yarn, stood watching from the side with his feet planted firmly in rubber boots.

Jiro gazed on the scene for some time as Sodeko continued the same action while casting serious glances at Jiro from underneath her overgrown black pageboy that gave her a ferocious air. Eventually, Jiro said curtly, “Hey, there’s no such thing as a factory without a name, ya know.”

Sodeko glared at him as she thought it over, then responded without pausing her hand, “—It’s called Swing Fact’ry!” Who cares?!, her tone seemed to say.

Looking down from where she was, Hiroko involuntarily opened her mouth wide in a soundless laugh.

“Look, this is a machine!” said Sodeko to Jiro, still serious as she pressed her free left hand against the cracked wood grain of the swing’s pole.

This time Jiro moved without a word to stand next to Sodeko. Then he took up the other piece of broken rope and began to wave it around even more wildly than Sodeko as he got into the swing of things. After whipping it around and around, Jiro, with the characteristic agility of a boy, lifted his legs up and swung from the end of the swaying rope. When it seemed about to stop, he kicked the ground with his rubber boots and off he went, swinging this way and that. It looked as if his feet were blindly kicking at the earth: sometimes they would just touch, but at other times they would miss and whip the air.—

At some point Hiroko became entranced, and unawares, her chin began to bob in rhythm as if to give him a push.

Sodeko changed hands, but she stood transfixed watching Jiro.

Once he tired of this, Jiro disappeared for a little while, and when he reappeared, he was dragging a loose board with mud on one side. He lugged it to where the rope swing was hanging, and then tried with all his might to fasten it on so it would resemble a real swing, but the rope was thick and the board was thin and wide, and Jiro’s small chilblained hands were no match for the task.

Though positioned awkwardly, he kept trying, using even his knees to somehow make it work, but no matter how many times the board fell, he continued to give it his best without so much as a peep.—

From the second floor, Hiroko began to find it hard to watch the efforts of Jiro, who had nothing you could call a real toy either at home or at the day care.

Wondering what was going on with Tamino, Hiroko went down to the six-mat room and was taken aback. Usui, his back to Hiroko, was leaning against the pillar face-to-face with Tamino. At the sound of Hiroko’s foot‑steps, Tamino looked up, but Usui took something in front of him, folded it up deliberately, and placed it in the front fold of his kimono, clearly aware of Hiroko’s presence but not moving his head in her direction.

Hiroko decided not to go to the four-and-a-half-mat room but instead slipped on the wooden sandals at the door and stepped outside.

5

In the evening after the children went home and things quieted down, Tamino and Hiroko turned their attention to crafting eye-catching leaflets, deliberating over such things as the size of the letters and the borders, while they cut a variety of large and small, square stencils for mimeographing leaflets.

The finances of the day care had taken a real hit since they began to do support work. Hiroko was no longer just taking care of the children who came every day. She decided that as a convenience to mothers who needed to run out for something, she would also take in children at the spur-of-the moment for a trifle and thereby make the day care more accessible to everyone. But quite apart from its labor aid aspect, the day care had been sustained by women from progressive families, and she was determined to expand in this direction as well.

Even if they could cut the stencils, they didn’t have a mimeograph. They had to go to the clinic for that. Tamino was about to go out in her usual skirt and clogs when Usui arrived.

“What’ve you got there?”

He took the rolled-up paper from Tamino’s hands, looked it over, and handed it back.

“They’re probably using it over there right now.”

He often spoke like he was thoroughly acquainted with the activities of every post. “Really?! What a pain. Did you just go by there?”

Without answering, Usui said, “If that’s all you’re trying to do, I know a place that should be able to take care of it—”

“You shoulda said something sooner! Let’s go! All right?” “I think it’ll be all right tonight. . . .”

Hearing these words directed at the honest Tamino, Hiroko recalled witnessing Usui’s cavalier attitude when she happened on them as she came downstairs the other day.

They went out, and Tamino took care of the work, but a day later, she suddenly brought up, “I always thought port was just Western saké, but it isn’t.”

*

Then one night Tamino had pulled the light down low and was repairing a hole in her stockings when she said, “Might be goin’ someplace else one of these days.”

She said it as if she were talking to herself.

It was a very windy night, and Hiroko sat at the desk beneath the dim light to go over the books. Without raising her face, she kept on writing numbers and quite naturally absorbed Tamino’s words with a murmur.

“Hmm . . . Something promising?”

Just three months ago, Tamino had lost her job at the Yama Electric Company because of union activity. Until then she had always lived the life of a factory worker. She was invited to the union office, but she liked the workplace, she said, and she was sure she’d get back in there. In the meantime, she had been helping Hiroko.

Looking down, Tamino ineptly pulled at the tangled thread with youthful roughness and said, “Nothing’s settled yet.”

Then after a bit, she added, “Mr. Usui’s really happy that the thing he’s been waiting for has come through. . . .”

Without realizing it Hiroko raised her head and, looking at Tamino’s down-turned face, used the fingers not holding the pen to slowly twist her lower lip. Tamino was still looking down at her mending.

“What do you mean ‘come through’? . . .” Some likely conjectures popped into Hiroko’s head.2 “That doesn’t have anything to do with you, though, does it?”

Tamino didn’t respond directly. After a little while she murmured, half engrossed in her own thoughts. “It sounds like everybody’s having a hard time because really useful women are few and far between.”

As if her eyes had just been opened, Hiroko realized the significance of what Tamino was thinking but couldn’t say.

“It’s not a job?”

“. . .”

Hiroko felt a rush of complicated affection for young, honest Tamino. Most likely Usui had said something to her, and that must have inclined her to take on a role that might be considered to have more positive meaning than being active in the factory. But Hiroko had long harbored doubts about the way young female activists were sucked into the roles of secretary or housekeeper as a matter of expedience. Hiroko thought it over as she continued to twist her lower lip, but then she spoke slowly, “Over there, it seems they’ve made a point of saying it’s no good to have female comrades live with men under the pretext of calling them secretaries or housekeepers, even making them have sexual relations with them. I read about it somewhere.”3

“Yeah?”

Tamino lifted her head. She looked at Hiroko with her brows raised sharply and started to say something, but then stopped and resumed her needlework.

Putting her socks away at last, Tamino went through the roll of supporters and began to write their names on brown envelopes.

As the evening advanced, the wind rattled the tin eaves. Whenever the cold, wintry wind died down, though, there was a stillness all around, suggesting the roads had iced over. Tamino was writing with a fountain pen she held at a strange angle near the tip. The worn-out pen rubbed on the slippery surface of the paper with a squeak, squeak.

Listening to the squeak, squeak, Hiroko’s mind recalled another scene. In a house consisting of two rooms separated by cheap sliding doors decorated with a landscape of pine trees on a mountain, Hiroko was writing something at the kitchen table. It was already nearing dawn. Tired, Hiroko was struggling with her ideas, which were not coming together, but from the other side of the sliding door, sounded the same squeak, squeak of a pen. Even from this side of the door, the sound couldn’t help but make her feel the lively vitality of the ideas being written with such an even-paced speed and without any hesitation.

Hiroko stopped her own hand and lent an ear to that sound with pleasure. Then, through the sliding door she said, “Excuse me . . .”

“—What is it?”

“. . . Please don’t go protesting, okay?”

Hiroko’s lips were forming a smile as she listened for signs from the other side.

Jūkichi, apparently not grasping the meaning of Hiroko’s words right away, seemed to be straightening his posture. In a minute, he burst out laughing. “—Is that what you’re talking about!”

“That’s hardly my style now, is it?” And the squeak, squeak promptly resumed.—

Hiroko felt an emotional bond with Tamino, who was setting out on the path of a class-conscious woman whose joys and trials would not be unlike the ones she herself had experienced and would continue to experience.

When Hiroko had been detained by the police, she looked out the window and discovered that a mother sparrow had built a nest at the top of a Japanese cypress. She said, “Ah, poor thing! Building a nest in a place like this.”

As soon as she said that, a man with a heavy beard who was standing there said, “What do you mean, ‘poor thing’? She knows she’ll be safely protected.” He looked Hiroko up and down. “Somebody like you’d be fine if you had a baby. You’d dote on it, too, I can tell.”

Hiroko stared straight at the man and said, “Please let Fukagawa come home.”

The man lapsed into silence.

Hiroko had been released and gone to live at the day care at the summer’s end, when Ohana’s friend was hurt badly and had to be hospitalized.

Chiibo was entrusted to her at the day care. Putting him to sleep in the four-and-a-half-mat room on the first floor, Hiroko sat by his side, shooing flies away with a fan while she read a book. When he opened his eyes, he started crying and simply wouldn’t hush up. He cried so much he began to sweat. Hiroko had a sudden thought, and pleased with the idea, said to him, “Okay, how’s this? Little Chiibo, you’re not going to cry on me now, are you?”

And as she said this, she opened her white blouse and offered her own breast to the crying baby.

Chiibo looked shriveled, and the color of his face and the soles of his feet was poor. He opened his mouth like a thin red ring and rooted around, but just when she thought he had taken the nipple into his mouth, he thrust it back out with his tongue and began to cry again, this time with even greater ferocity.

After trying this three or four times, she gave up and, at a loss herself, spoke to him as if he were a child who could be reasoned with. “Hey little guy, you’re out of luck if you don’t like this.—Come on, Auntie’s not so bad.”

A little over an hour later, Hokkaido-born Ohana came back. “Sorry about that. It’s awful hot out there.”

Ohana undid her sash, removed her large-patterned summer kimono to her waist and placed a hand towel on her shoulder.

“Lookee here, little crybaby.” She offered him a dangling black nipple. Breathing hard, Chiibo dove in.

Hiroko explained what had happened. With complete nonchalance, Ohana said, “Of course he’s not gonna suckle. If it’s not a breast that’s been nursing, it’ll feel cold, and he’s not gonna like that.”

She took the towel from her bare shoulder and wiped the sweat off her face. Hiroko couldn’t forget that evening. That her nipples were cold nipples.4 And the sight of Ohana, though splendidly endowed, just managing to stick her malnourished baby, pale legs sticking out from his diaper, to the breast that was at least warm. It struck Hiroko that the sorrow and outrage of women in this society could be found in these two images.

That night, after she got into bed and turned out the light, Hiroko spoke to Tamino using a casual and calm tone.

“Be careful you don’t use up your enthusiasm for something strange or too personal, okay?”

“. . .”

“I’m sorry, I know it seems like this is none of my business, but in the work we do, we can only judge a person by the work they’ve done. Don’t you agree? And I feel like you haven’t done any real work yet with Mr. Usui. I feel like we hardly know him. . . .”

Hiroko felt Tamino stir in the bed next to her. After a while, Tamino said earnestly, “—I guess so, now that you say it.”

She spoke slowly. After a while, Hiroko heard her sigh.

6

Early in the morning, someone from the local police station showed up. He wandered around as if he had no particular purpose.

“Toyono’s coming around today, I suppose.” He cast a suspicious glance at the footwear in the entrance. Hiroko and the others had never heard of a Toyono.

“What, you don’t know him? Liars. I’ve got someone who saw you heading out to meet him.”

This was just a wild accusation. He was about to turn and leave when he stopped. “Wait! What’s that?”

When they looked at what he was pointing to with the end of his walking stick, it turned out to be the day care sign that had been tossed into the muddy ditch the other day.

“Whaddya mean, ‘what’?—Dontcha know?” said Tamino, coming out. “It’s been up for a year already.”

“Who said it was okay for you to put it up?”

With an air of annoyance, Tamino started to say, “So long as we’re here—” but he interrupted, “Don’t be so sure of that.” He made it sound as if there were some special meaning behind his words.

“If we say something doesn’t exist, then it doesn’t exist, you see. Take KOPF. The people belonging think it exists, but we’re not letting it exist.”

When KOPF, the Japan Proletarian Culture Federation,5 was started up in 1931, that meant the creation of the first cultural organization unified under. . . . . . . Acknowledgment of this notification had been refused by . . . . , and this spring, this was compounded by . . . . . . . . . . . . .

After the man left, Tamino spat on the ground. “Damn! Hate that lousy bastard.”

The next day, around two o’clock in the afternoon, Hiroko was working on drafting the newsletter on the second floor when she heard someone coming up the ladder, one heavy step at a time. The footsteps were unfamiliar. She turned around with pen in hand, and there was Mrs. Inaba from Shōki Hosiery, who had come up carrying a furoshiki-wrapped package. A large white radish was sticking out from the package.

“Oh, it’s you, Auntie. . . . What’s wrong? Something I can do for you?” “Did Mr. Ōtani stop in?”

“No, he hasn’t.”

Hiroko had an appointment to see him that very night. Mrs. Inaba’s eyes darted about, conveying something out of the ordinary. “Then that must’ve been him after all.”

Hiroko stood from the chair so fast it surprised even her. “What happened . . . ?

“—I, I saw it all.”

Something in those words made Hiroko shudder.

It was Mrs. Inaba’s turn to host the mutual aid association meeting, so she had taken the day off to do the shopping. As she turned this way across the big avenue in front of the train station, she saw a man who looked like Ōtani walking along with a younger man. Mrs. Inaba wanted to make sure it was him before calling out, so she followed them a bit when the younger man parted with him at the corner by the radio shop. After crossing two alleys, a man in Western clothes appeared from beside the penny candy shop, and in a second two more men came out from nowhere, and they closed in on Ōtani.

“Hey!”

They said something, and Ōtani tried to slip through, when the three men quickly surrounded him and some scuffling began. It all flashed before Mrs. Inaba’s eyes like a sharp, soundless lightning strike. Instead of continuing on, they started heading back toward the station, so half covering her face with her sleeve, she ducked under the storefront eaves. What she saw was the form of a man trying to slip through but surrounded on three sides and handcuffed. Despite the fact that his hands were nearly immobilized, the man was calmly straightening the front of his kimono—she was sure it was Ōtani.

When Hiroko finished listening, she felt her throat clench and her voice fail. For a while, she pressed her mouth with her right hand still holding the pen, then croaked out in a dry voice, “Was Ōtani carrying anything?”

“Hmm . . . I wondered that, too.—He was carrying what looked like a teeny tiny package, I think.”

“The man who parted with him—What was he wearing? Western clothes?”

“You think he’d be in Western clothes? Naw, he was wearing the kind of thing you see all the time on students, a splash-patterned kimono, I guess.” Hiroko’s eyes narrowed as if to pierce with her gaze. Splash pattern . . .

splash pattern. Hmm . . .6 “You didn’t see his face, huh?” “How could I, he turned the corner first.”

Taking two rungs at a time, Tamino came into the room. “Did you hear?” Her eyes glared over her flushed cheeks.

“Won’t they be coming here?”

Mrs. Inaba looked from Hiroko to Tamino, then moved her gaze back to Hiroko. Hiroko noticed this and said, “It’ll be okay!”

She turned to Tamino and signaled with her eyes.

“This is a day care, right? If something weird happened, the mothers would never stand for it, right?”

Even though she wasn’t sweating, Mrs. Inaba kept dabbing around her nose with her striped apron wrapped around her finger. “The way they treat the pruletariat—you’d think we wasn’t human!”

When Mrs. Inaba had gone downstairs, Tamino impatiently pulled down a trunk from the bookcase with her two strong arms. While she carefully got rid of the scraps of paper they didn’t need, she murmured, “Couldn’t stand them cleaning out this place.”

There was no telling about that. When the Friends of the Soviet Union Association spread to workplaces in each district and representatives from each workplace were selected to join a study tour, then those activities became more restricted.

It wasn’t as if Hiroko had never imagined there could be repercussions from the links between the streetcar support activities and Ōtani’s position. She sent Tamino out to call a certain place to have them inform the necessary people.

When Jūkichi was arrested, Hiroko had thought she was utterly calm, but twice she hit her forehead hard on a crossbeam suspended across the perfectly familiar ladder in Ōtani’s house. Hiroko recalled Ōtani silently gazing at the traces of the injury, then saying,“Well, have something to eat.”

The composure with which he had sat Hiroko down at the table. As she conjured up various scenes of their work together, her stomach churned with bitter regret.

Some time ago, Hiroko heard a story from somebody about Ōtani’s climbing a tree to escape danger in the nick of time. She found the story amusing and told it to Jūkichi. “Did that really happen?” she asked.

Jūkichi studied Hiroko’s face and said, “He’s capable of amazing feats.” He laughed as he answered. Much later, when Hiroko thought about the way Jūkichi had responded, she found there was something about it that deeply impressed her. Jūkichi and Ōtani’s friendship went beyond telling tales about each other. That such a friendship served as a spring for propelling history forward was a value Hiroko was recently beginning to comprehend.

But was it really inevitable that Ōtani would be arrested? As Hiroko thought about it, she thought he, too, must have regrets. For example, the man in the splash-patterned kimono. . . . What if the splash pattern was that splash pattern? Had Ōtani had any basis for his conviction that something like this wouldn’t happen?

Hiroko was plagued with feelings of remorse.

*

Barely a day later, Tamino was arrested at the day care.

On her way back from getting deworming medicine for the children, Hiroko found Jiro and Sodeko standing watch near the bridge over the ditch. As soon as they saw Hiroko, they clasped hands and galloped toward her with all their might. The instant she saw the children, Hiroko for some reason immediately thought, Fire! She, too, started to trot toward them. Jiro grabbed at her skirt and said, “You know what? Listen!”

Then breathlessly, “They took Miss Iida away!” he reported.

“When?”

“Just now!”

“What about Miss Ogura?” “She’s here.”

That morning, the newspaper had announced the end of the streetcar dispute. Tamino spread open the paper as she stood. After putting it down once, she picked it up again. “It’s disgusting that we have to learn about this from the bourgeois morning newspaper!”

Her frank words struck a chord in Hiroko. Hearing this, Ohana said, “Well, now I’m really in a pickle with the folks in the neighborhood. I went around collecting funds, asking them to give even if it was only a sen.”

Tamino had been preparing to print flyers to inform the parents who had donated funds that the employees had lost because they hadn’t exerted their true strength. That was when she was caught.

When Hiroko entered, Ogura said, “Oh, thank goodness!”

Two men had come in as if nothing was the matter and gone up to the second floor without so much as a by-your-leave. Tamino followed them right up, but when they came down, one of them was carrying something with the title printed in red ink. He used it to slap Tamino on the face.

“‘Don’t act like you’re innocent! You’re a party member, aren’t you? Ōtani’s spilling it all,’ they told her. Oh, she was badly beaten.”

As she recounted what had happened, Ogura’s eyes welled with tears. With unconscious sharpness, Hiroko said, “That’s a bunch of lies.” They’d use some document that couldn’t possibly have been there as a pretext. Hiroko had heard about things like that happening with KOPF, too. As she tried to cheer Ogura up, Hiroko took a large white sheet of paper on which she wrote about Sawazaki Kin who was being held in police custody for no reason at all for nearly three months and then about Tamino, and hung the paper from the lintel above the entrance where everyone coming in would see it.

She had evaded arrest this time, but she had no way of knowing if it would last until that night or the next day. She climbed to the second floor by herself. Only the area near the table was in disarray in the three-mat room. Tamino’s green pen had apparently rolled off the table and the nib had pierced the tatami mat underneath. Hiroko pulled it out quietly and, as she fiddled with it, decided to hold a meeting with the parents when they came to pick up their children that night. Then she went downstairs and entrusted a package to Ogura. It was a jacket for Jūkichi in prison.

Notes:

1. Added to the postwar version: “because his legs were swollen from torture.”

2. Added to the postwar version: “In any case, there had no doubt been some contact between Usui and the Party organization.”

3. Added to the postwar version: “In Hiroko’s circle, ‘over there’ always referred to the Soviet Union.”

4. In the postwar version, the line reads: “That her nipples were the cold nipples of a woman who’d never given birth.”

5. Gloss supplied by translator.

6. The postwar version adds, “Usi always wore a splash-patterned kimono.”

By April 1935, Miyamoto [Chūjō] Yuriko’s (1899–1951) husband, Miyamoto Kenji, and many of the leaders of the proletarian movement were either imprisoned or released after political recantation. Moreover, the Communist Party—and by extension, whatever was left of the proletarian movement—was thoroughly discredited in the media by the scandalous accusation that they were exploiting women by asking them to serve as cover wives (or “housekeepers”) for activist men who had gone underground. Such was the moment Yuriko, who would return to prison in May 1935, seized to publish “The Breast” in the highbrow Central Review.

From the time of her debut publication, A Flock of Poor People (1916), at the age of seventeen, Yuriko showed an ambitious literary sensibility as well as a sensitivity to class inequality. Extended stays in the United States and the Soviet Union, the latter with companion Yuasa Yoshiko (1896–1990), a scholar and translator of Russian literature, fostered her feminist-socialist consciousness. When she returned to Japan in 1930, she threw herself into proletarian organizations, joining the Writers League; editing the journal Working Women with Sata Ineko and Wakasugi Toriko; organizing writing circles for workers, including the Shimosuwa Circle represented by Nagano Kayo; and writing autobiographical works and essays about life in the Soviet Union.

This short story was published in Central Review, April 1935, and translated by Heather Bowen-Struyk in ‘For Dignity, Justice, and Revolution: An Anthology of Japanese Proletarian Literature’ (2016, University of Chicago Press)

Heather Bowen-Struyk is the guest editor of Proletarian Arts in East Asia (a special edition of positions) and a coeditor of Red Love Across the Pacific. She is completing her manuscript on love and proletarian literature while teaching at the University of Notre Dame.

Heather Bowen-Struyk is the guest editor of Proletarian Arts in East Asia (a special edition of positions) and a coeditor of Red Love Across the Pacific. She is completing her manuscript on love and proletarian literature while teaching at the University of Notre Dame.

Translated by Heather Bowen-Struyk