Revitalized as an inclusive martial art, sumo has made a comeback through grassroots clubs like Sumo Sundays, reflecting a rich history of resilience and community.

Arriving with the first immigrants and nearly extinguished in the internment camps during the Second World War, sumo was the favorite sport of Vancouver’s Japanese Canadian community. Today, nearly 80 years after the war’s end, sumo has made a comeback in Vancouver, reflecting the community’s resilience and forward-thinking nature.

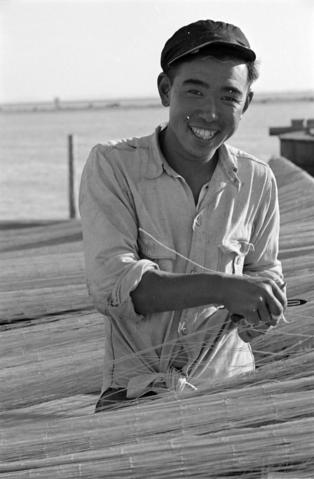

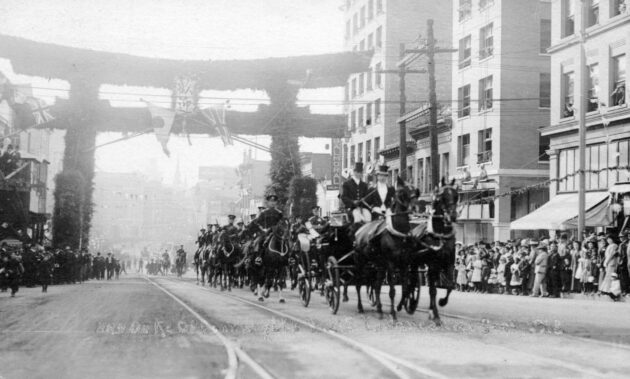

From 1877, Japanese laborers moved to Canada to work in the fishing, forestry, shipping, and railroad industries. They carried sumo with them to isolated logging camps, ports, and factories. It was a common pastime, rivaling baseball, among Japanese manual laborers, and sumo rings (dohyō, 土俵), were established in several Japanese cultural institutions around British Columbia. Japanese communities along the West Coast, as well as in Hawai’i and Alaska celebrated New Year’s with sumo tournaments, uniting the community across generational and social lines. Throughout the year as well, tournaments were frequent and well-attended, generating interest beyond the Japanese community. As early as 1905, The Vancouver Daily Province reported on a sumo tournament held at City Hall Auditorium:

The battle consists in keeping feet on the mat, the opponents lean heavily on each other and toward the centre. This brings many feints and sidesteps into play that are unknown in American wrestling, for very often a man is defeated by the force of his own weight carrying him outside the line…The opponent was so heavy that nothing short of an earthquake or his own weight could budge him. So the nimbler man encouraged him to push hard, till the muscles of his fat sides stood out in rolls. Then something happened. The Nimble One jumped in the air while the heavy fellow fell like a log between his opponent’s feet. And how those Japanese did howl and yell “Banzai” to the lucky boy who used his head.

The somewhat bemused tone of this observer reflects how sumo has generally been regarded in the West — as a slightly comical cultural curiosity. However, at the same time the reporter manages to grasp the essential spirit of the sport: the importance of brains over brawn.

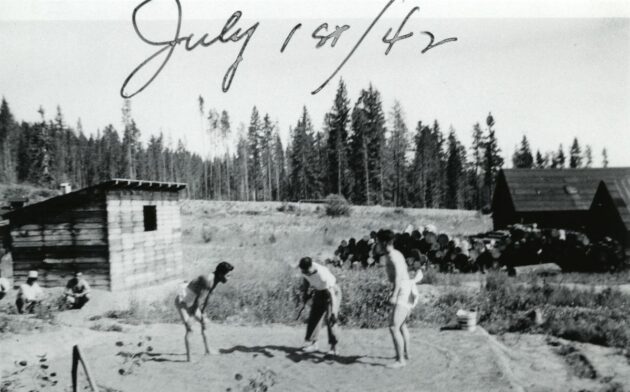

Under the bleak and primitive conditions of the WWII internment camps, sumo was practiced as a way to pass the time. Japanese Canadians’ properties were liquidated, destroying the wealth that the community had worked generations to build. After the war, they were not allowed to return to the Pacific Coast until 1949. Due to this extreme disruption to and indeed shattering of their community, their businesses, and their lives, it is estimated that only around 25% of the Japanese Canadian pre-war population returned to British Columbia. Sumo went on a long hiatus.

Under the bleak and primitive conditions of the WWII internment camps, sumo was practiced as a way to pass the time.

In 1977, the Japanese Canadian community association Tonari Gumi founded the Powell Street Festival to celebrate the spirit of Vancouver’s historic Japanese Canadian neighborhood, Paueru-gai (パウエル街), in the Downtown Eastside. This marked the beginning of the movement of Japanese Canadians to reclaim their cultural identity after decades of cultural assimilation and displacement. The festival was a means of reconnecting with Japanese arts and traditions as well as an opportunity to teach these traditions to the next generation and to the wider society. The festival also dovetailed with the Redress Movement, which was gaining momentum at that time, with Japanese Canadians demanding a formal apology and compensation for their internment, loss of property, and the violation of their rights as citizens. The movement led to the Canadian government officially apologizing and offering modest compensation in 1988. Held in the heart of what was formerly home to 8,000 Japanese Canadians, the Powell Street Festival has become a platform to celebrate Japanese Canadian culture and political activism.

Since the earliest days of the festival, one of the main events has been a friendly sumo competition organized by the Sumo Fun Club, open today to challengers of all backgrounds and body sizes. Because of the community’s history and the festival’s presence in the current Downtown Eastside (one of the most economically marginalized neighbourhoods in Vancouver), inclusivity has been an important theme of the festival, reflecting the values of the Japanese Canadian community. The Sumo Fun Club organized the sumo exhibition at the Powell Street Festival for more than 40 years, before passing the torch in 2017 to organizers Shane Peckhold and Lydia Luk. Though the event had originally followed a traditional, exclusionary attitude towards women, within the last eight years it has gradually evolved to include women and non-binary competitors.

To offer a consistent space to practice sumo, Pecknold and Luk also went on to co-found the Sumo Sundays club in 2022 with Kayla Isomura, a regular participant of the sumo competition. Pecknold lived for several years in Japan, where he developed a passion for sumo, and upon his return to Canada has sought to reinvigorate Vancouver’s sumo tradition and “normalize sumo as just another wrestling style, that anyone can play, regardless of size.” What makes Sumo Sundays unique, and also successful, is their rigorous emphasis on openness and inclusivity. The club attracts a wide range of participants from all walks of life, not only Nikkei proudly reviving their culture, but also martial arts enthusiasts, members of the queer community, and many others. Newcomers are encouraged to practice techniques and breakfalls without feeling pressure to face an opponent, keeping injuries to a minimum, and allowing members of all skill levels to participate.

While the Powell Street Festival is held only once a year, Sumo Sundays take place regularly in a dohyō on the top floor of the historic Japanese Language School & Hall, which overlooks the Port of Vancouver, once bustling with Japanese workers. Established in 1906, but closed from 1941 to 1952, the school is the only property to have been restored to the Japanese Canadian community after WWII and is now a powerful symbol of the community’s resilience. Sumo Sundays’ website also acknowledges that training takes place within the former 100-mile exclusion zone that Japanese Canadians were forbidden to enter during WWII as well as “on the unceded traditional territories of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh nations.”

Sumo is inherently body positive. Sumo wrestlers need a combination of strength, agility, and flexibility, which does not guarantee that one body type will always prevail. Indeed, smaller players who can skillfully use their opponents’ power against them are often victorious (as noted in the 1905 article). At Sumo Sundays opponents are matched by weight, irrespective of gender. In traditional sumo, women are considered to be kegare (穢れ), “unclean,” and not allowed to enter the sacred dohyō. When the Mayor of Maizuru in Kyoto Prefecture collapsed due to a medical emergency at a sumo event in 2018, female medical personnel in the audience rushed into the dohyo to perform CPR, but were repeatedly asked by a referee to leave. Salt was then thrown around the ring to “purify” it after the female medics stepped out. The Japan Sumo Association later apologized for putting the Mayor’s life at risk. Likewise, in 2000, the female governor of Osaka Prefecture, Fusae Ota, was forced to present the Governor’s Trophy outside the sumo ring. As its popularity has grown, Sumo Sundays’ all-gender sumo tournaments have likewise been subject to an online backlash. Some traditionalists claim that women fighting men offends the spirit of sumo, while others maintain that women are incapable of beating men (despite the fact that this is a frequent occurrence!)

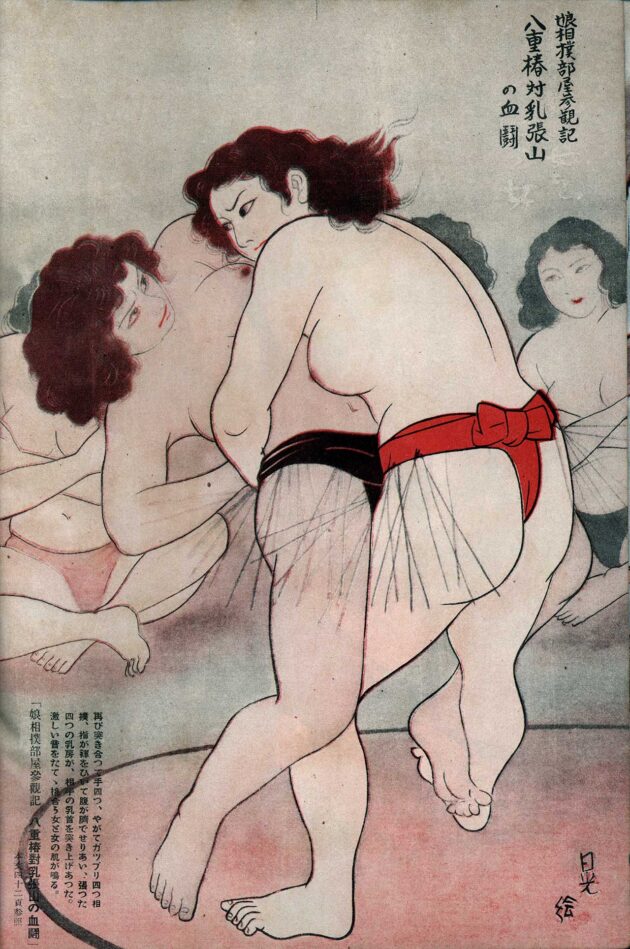

Women’s participation in sumo, however, is not a new phenomenon. The Nihon Shoki, Japan’s second-oldest book from the year 720, describes a match between two court ladies. From the Edo period (1603) until the 1950s, onnazumo (女相撲), women’s sumo, was a popular event held at shrines and temples, and folklore in many rural regions of Japan note women’s sumo as a way to pray for rain. It seems that the cultural prohibition against women entering the dohyō began only in the Meiji era (1868–1912). Despite the historical evidence, only amateur sumo events are open to women today in Japan. Recently, Little Miss Sumo (2018), a Netflix documentary about Hiyori Kon (今 日和), a young woman fighting for women’s rights both inside and outside the dohyō, has inspired interest in women’s sumo around the world.

Though sumo is Japan’s oldest sport, it is the most recent Japanese martial art to take root overseas.

The atmosphere of Sumo Sundays contrasts markedly with the machismo of many martial arts clubs. Partially because sumo is not an established martial art in Canada, it offers an unparalleled opportunity for crossover training. Practitioners of various grappling martial arts — Greco-Roman Wrestling, Judo, Football, and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu — can apply their knowledge and cross-pollinate with sumo techniques. Some people are even drawn to sumo specifically to test their skills against bigger and stronger opponents.

Shane Pecknold’s enthusiasm has led to a revitalization of Sumo Canada, a previously defunct sporting body. In September 2024 he represented the Canadian team at the Sumo World Championships in Poland along with two other participants of Sumo Sundays, Ryan Kimoto and Bryan Chan. Ironically, the Japanese women’s team earned more medals than the men’s.

Though sumo is Japan’s oldest sport, it is the most recent Japanese martial art to take root overseas. Today, however, sumo is increasing in popularity and being adapted into new forms, such as a beach sumo club. The beauty of sumo is that physical size or strength does not always ensure victory; a determined, crafty player can succeed against a dominant, larger opponent. That’s the story of Vancouver Sumo: against the odds, a progressive sumo club is re-establishing traditions by forging a new martial arts culture in the heart of Pauerugai, Vancouver’s historic Japanese Canadian neighbourhood.

LEWIS MIESEN is a freelance writer and translator who resides in Kyoto. A lifelong traveler, he rode his bike for two months across Japan. He enjoys exploring cultures and making new friends from all over the world. In addition to writing for Kyoto Journal, he is also the Marketing Director.

‘Sumo Revival in Vancouver’s Historic Japanese Canadian Neighborhood’ is part of KJ 108, Fluidity 2, 2024.