[M]elinda Heal is from Canberra, Australia, where she completed a double degree in Asian Studies (majoring in Japanese) and Visual Arts (with a major in Textiles). She arrived in Kyoto initially as an exchange student, and while her fellow exchange students were focusing on grammar and kanji, Melinda took up katazome (stencil dyeing) at Kyoto Seika University. She returned to Seika as a Monkasho (Japanese Ministry of Education, MEXT) research student and has now spent five years in Japan. At present she is finishing her Master’s degree, specializing in traditional dyeing techniques.

On her blog, Melinda contrasts two ways of describing art works. The first, she satirizes as “art-talk”: “My work is about juxtaposing the ideas of transience and permanence, in all their nuances and alluding to the transcendental nature of our existence.” But to describe her own work, she far prefers a more down-to-earth style: “I make dyed textiles. I love parrots, I think they are beautiful and have incredible colours, behaviors and histories. Dyeing fabric is a process I enjoy and I hope viewers will enjoy the energy, colours and nature in my work too.”

Lisa Allen talked with Melinda in Kyoto in January 2015.

LA: First of all, why the birds? It’s such a beautiful motif, and they are in so many of your works!

MH: Well, we have so many birds in Australia that don’t exist in Japan. Since coming to Japan they’ve become stronger in my imagery because they’re not around. So it’s partly to say “Hey, Japan, check it out! Australia’s got all these amazing birds, and isn’t it amazing, these things you’ve never seen before?” They’re really colourful, and the dyes that I’m using are very vivid, so you can actually get those colours to pop out, and the fabric moves like the movement of birds…

When I came on exchange we had a small 90 by 70cm project, then we were let loose to make whatever we wanted, so I decided to make a yukata, and did a small stencil that was repeated. I decided to use Australian flowers and birds, and from there it just took off. And the reactions that I got were maybe what made it stick too — like “Wow, that’s not a real bird, what are you talking about, they don’t exist.” “Oh yes they do! This is what they actually look like!” People are really surprised. Sometimes they think it’s Okinawan, because of the bright colours and the strange tropical-looking flowers. I went to Okinawa last March, and saw some plants there that we have in Australia.

What’s your favorite bird?

That’s difficult! Maybe Orange-bellied Parrots? They’re the most endangered species (only about 50 are left in the wild). They are from Tasmania, and they’re migratory.

Have you ever had the urge to use cranes in your images?

No, I would feel wrong about it.

Even if they were Australian cranes?

No, that would be different. Somehow I’m hesitant to do Japanese birds. Last year, in April, I was in a group show where each person was asked to choose a different area of Kyoto. I chose Daimonji, and because I didn’t want to do just a mountain, I ended up putting birds in there, tombi (Black Kites). That was the first time I had ever done Japanese birds, but it felt strange. For one thing, it was all brown, brown and more brown, it wasn’t exciting in the same way.

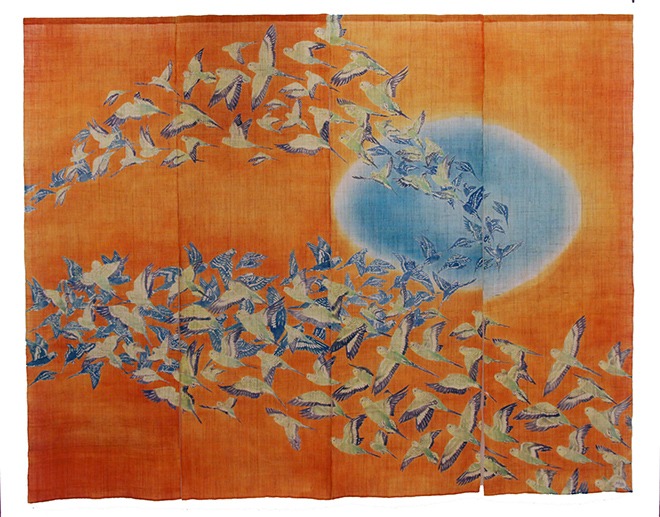

Usually my pieces grow from a bird or an idea, sometimes an endangered species that has some story around it, like fragmentation of habitat. With the white birds (Little Corellas, in “Shatter the Immense Summer Sky”) I just loved that movement and I wanted to depict that somehow. So, I do a lot of sketching, watercolour paintings, sometimes modifying the images digitally, then go big, enlarging everything. I have such a large space at Seika now, I feel like it’s a waste not to use it to go big. It’s amazing to have the chance to do large work.

What is your process in dyeing?

I first studied katazome. When I came back as a research student in 2011 Kyoto Seika had just decided to teach yuzen, a process historically used for kimono, and one of the teachers thought it would be a good opportunity to rejuvenate it and teach it to students because the materials and the tools are quite similar to katazome. Now I’ve started layering both techniques, and layering fabrics as well.

Is this a new take on an old technique?

It’s not like it hasn’t been done before. For example a noren [a split curtain for doorways] hangs in space and it’s still a textile, but in terms of artwork, maybe my work is something new. There are shibori (tie-dyeing) artists, and people doing fibre art, who do installations, they do things in space. But I haven’t seen people using yuzen or katazome in that way. I’m trying to make it a bit more contemporary.

When I came here on exchange, the thing that shocked me most about Japanese textiles is that they are always dyeing fabric then stretching it out and putting it on something solid, so it becomes like a painting. You’ve gone to all this trouble to dye a piece of fabric that moves and has texture, and is light, and then you go and flatten it. What I’m trying to do now is taking it back to being fabric, keeping it floating in space, or see-through, or retaining some kind of textile-ness about it.

Do you like one of those techniques more than the other?

They are two different things, visually and process-wise. Stencil dyeing (katazome) is really cool because it lets you repeat things. Once you’ve got a stencil cut, you can repeat it endlessly; you can flip it and do interesting things to make it more diverse — but you still only had to cut one stencil. So it’s quicker. But everything in the design has to be connected so the stencil doesn’t fall apart — it ends up having a certain rigid look about it. If I use it for birds, it’s like the birds are too stiff, but hand-drawn with yuzen they are much more free, with more movement. Plants or things that have more substance are easier to depict with stencils, so that’s what I’ve been doing recently.

How do you choose your colours?

Just by instinct, but for some reason they’re different from what Japanese people would use. They look at my work and say “I would never use those colours” — apparently they’re bolder and brighter than what they would use. That’s just because I’m using the original colour of the birds or the flowers, or a slightly modified version of the real colours. Maybe that’s just a reflection of what Australian colours are, compared to Japanese colours. The sky is bluer, and the plants are more vivid…

Who did you learn this technique from?

On my year of exchange Toba-sensei was my teacher. Now she’s my supervisor — she has been really generous in helping me. She’s a master of katazome. She works on big, sliding-door-sized dyed art pieces, in picture-style imagery onto fabric, making six- or even ten-panel works. Sometimes they’re sliding screens, sometimes folding. She has developed a liking for Vietnam — I think she went there on holiday and loved the culture — so her imagery is often Vietnamese buildings or run-down marketplaces or boats on rivers with reflections, in really bright colors, and that has become the flavor of her work. She has done big exhibitions in Vietnam and in Japan, and has gotten quite famous.

She included me in a group show at the Somé museum — six young people all working on traditional dyeing techniques, but not in a way that’s necessarily traditional. We were all either her students or former students, or her colleague’s students from Tokyo, and Hiroshima — she just looks out for us. Three of us were doing stencil resist, another two were doing wax resist, but not the technique normally used for kimono, instead it was used to make big panels like noren, with pictures of Japanese sweets, so the show was a different take on those techniques. We all had the same ideas about using a traditional technique and doing something fun with it.

What have been some of the challenges of being here as a student in this field?

Language, to start with, was a barrier. I did have some Japanese but coming into a university and learning something that’s traditional, it’s all Japanese language, so figuring my way through all that was interesting. And when I made a kimono, I had to go buy the fabric from a Japanese store that just sells rolls of fabric, and the store-keeper doesn’t speak English, so I gave him the piece of paper that my teacher wrote down, and asked to see some fabric, and he brought out all these rolls of silk — “This one, no, no, this one!” And you have to go to another shop to get the stencil paper. Once you have the Japanese skills it’s amazing to go into those kinds of shops and talk to them about the stuff that they’re making. One shop only sells bamboo stretchers to hold the fabric taut — the standard is 40 centimeters of bamboo with a pin at each end. That’s all that shop sells!

These places still exist in Kyoto, so it’s really interesting. I think that was part of why I wanted to come back to Kyoto — I could have applied to come back anywhere in Japan — but Kyoto has really got it going on, in terms of textiles. I have been to Tokyo, but it’s just kind of overwhelming, while Kyoto has a nice small city feel about it. It’s so traditional and at the same time not traditional at all. That’s really interesting to me. Like those little shops, they’re tucked in between a convenience store and a parking lot, selling just something that’s all that they have ever sold for a hundred years.

What other kinds of resources exist here in Kyoto (and Kansai?) for a student like yourself?

I like going to and find inspiration at Somé-Seiryukan, a gallery specialising in textile dyeing art — something I think is unique to Kyoto — and the Hosomi Museum because of its amazing collection of Rinpa School Japanese paintings, including lots of craft and functional pieces too. Exhibitions at Kyoto’s National Museum of Modern Art (MOMAK) — they had a huge exhibition a couple of years ago of katagami stencils. Then there’s the National Museum, the Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, various blockbuster shows held at department store galleries, like Takashimaya, Isetan, Daimaru. These are often free for students with the “campus members” scheme, or at least discounted. And there are many small galleries, especially in central Kyoto. There are always so many exhibitions on.

Also smaller textile-related studio/galleries such as Shop and Gallery YDS, a yuzen company established in 1899 — they have this amazing collection of old yuzen pieces, probably gathered over time by successive owners of the company, that they exhibit sometimes, which really show the way the technique has changed and how the yuzenartists of the past had such incredible skills. I was lucky enough to see the workspace upstairs too, where the artisans are dyeing and designing kimono. Chiso is another very famous yuzen kimono company (established in 1555!) with a gallery space near Sanjo/Karasuma in which they exhibit things from their collection from different eras. Often there are informative gallery talks too.

It sounds like it really energizes you! Have you ever found any kind of downside?

Well, I do have one story. With that group exhibition that we had, the gallery is apparently run by a kimono company, part of the old school of kimono companies in Kyoto. They opened the gallery in around 2005 as a venue for textile art, as opposed to kimono, but the audience and exhibitions for it are still pretty conservative. Most of the artists exhibiting are in their 40s and 50s. The exhibition I was part of was a regular thing where they ask an artist to choose a group of young people to exhibit, and it has become a series of up-and-coming artists, once or twice a year.

They always have an artist’s talk, like a talk-show, with an MC asking questions of each artist participating, but because we were young people it was suggested we should do something more interesting, and mix it up and maybe have video in the background and make it interactive… So we went to all this trouble, we made a movie in which each of us put together footage of our process and what we were inspired by, and we turned the lights down and we were going to talk to each other, with the movie showing, and we started doing it. Halfway through, this man stood up and told us to turn the video off and stop doing this weird stuff, just do a normal artist’s talk. We ended up having to do what they always do, standing up with a microphone.

That was such a strange experience — it made it obvious how Kyoto is still really traditional and conservative in terms of textiles. I think it’s hard for people to be really groundbreaking and contemporary here, as opposed to Tokyo, in terms of doing new things. Toba-sensei was there giving an introduction to our talk, and at the end, she was backing us up, that we were young and wanted to do something new and interesting… Maybe the way we did it was not perfect but that is why we did it.

How did you feel?

Awful, everyone felt awful. I understand that people think that; he just didn’t need to tell us there and then, in front of everyone, the way he felt about it.

It’s like you’re pushing the edge…

We tried to, but we got shut down. We were doing something right, I guess.

How about reactions to your own work, individually?

I often get comments about the “Japanese-ness” of my work, or the “Australian-ness” of it. Sometimes people react as if I’m doing something Japanese, not parodying it, but making it sort of strange — like I’d make a kimono or a folding screen or scroll or something and they’d be like, “You’ve done something weird here.” “Right, that’s because it’s not Japanese.” There’s an odd mix going on of Japanese and Australian, and some people take it in a strange way, and some people take it as it’s intended — my own take on the technique and what I’m interested in comes together in that way. I’m not trying to parody anything, imitate anything, or make it cheesy… One of my teachers is always on at me about that: “It’s too Japanese, what are you doing?”

The reaction in Australia is a little different. A good friend, Amy, uses katazome stencil technique, and in September we had a show together in Canberra at the gallery of the school of art that we went to there. We weren’t sure how people were going to react, but there were compliments I’d never get in Japan. “It’s fan-tas-tic!” “It’s fabulous!” All these funny Australianisms! As well as the visual aspect, they were like, “How did you do that? What is this?” There’s a real interest in the making of it.

We did an artists talk, too, a presentation where we showed images of the process, and people were shocked: “I didn’t know you went to so much effort to get that one image on a piece of fabric. That’s amazing!” I think there’s potential there for teaching it, or promoting it or even just being someone who uses that technique. There’s kind of a niche there that no one is using it, or hasn’t studied it, I guess. It will be interesting to see where that goes, taking it back to Australia, with people not having the background to know what it is.

So how do you feel about taking it to Australia?

Nervous. I feel a bit responsible, to get it right, to know what I’m talking about. But my teachers seem to think I’m capable of doing that, so that’s encouraging. It’s exciting, but terrifying as well. I’ll leave in May, and to force myself to keep going, I have already booked a small gallery for a solo show in Canberra in August — so I have to do something once I go back. It would be interesting to do natural dyes. Now I’m using chemical dyes, which are really bright, and are the easiest to use. But Australian plants, especially eucalypts, give out really strong oranges and yellows that could be used to paint on the silk — that would be really a full circle, to have the colour from that tree in the textile, but it’s a technical thing I haven’t nutted out yet… Now I’m trying to move away from kimonos and screens, more towards that fabric and installations, contemporary textiles feel. It would be really cool to do kinetic textile installations, moving things with sound and lights, eventually. That’s something I’d like to work towards.

Melinda’s website: www.so-meru.com

Amy’s: www.moyou.com.au