Mount Wutai: Visions of a Sacred Buddhist Mountain, Wen-shing Chou, Princeton University Press, 2018, 236pp

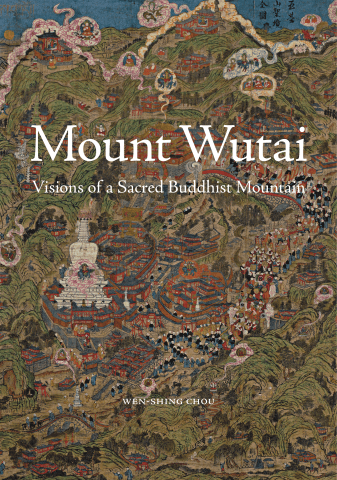

The Rubin Museum of Art in New York is home to one of 16 (or 18?) extant variations on a superbly detailed print depicting physical and esoteric features of the pilgrimage destination Mount Wutai in Shanxi Province, China. These images are derived from an immense (118 x 165 cm) woodblock carved at Cifu Monastery in 1846. In 2007, the museum curated a major exhibition of Wutai-related material, “Wutaishan: Pilgrimage to Five-Peak Mountain” in association with a landmark conference “Wutaishan and Qing Culture,” cosponsored by Columbia University. This is one of several fine books since published by presenters at that gathering.

To quote from Wutaishan’s UNESCO World Heritage advisory evaluation “According to the Records of Mount Qingliang, written by Buddhist master Zhencheng in the Ming Dynasty, the first temple built on Mount Wutai was created by the order of the Han Emperor in AD 68. This was at the time when India Buddhist masters visited China to promote Buddhism. They considered that in terms of topography Mount Wutai was identical to the Vulture Peak (Rajgir, India), where Sakyamuni lectured on the Lotus Sutra.” Wutaishan is also known as Qingliangshan (Clear and Cool Mountains). Since the fifth century CE it has been closely connected with Manjusri, the Bodhisattva of transcendent wisdom (Monju Bosatsu, in Japanese, Wenshu Pusa, in Chinese). This association is based on a reference to his dwelling place in a possibly amended Chinese version of the Flower Garland Sutra (Avataṃsaka, or Hua-yan in Chinese).

In 772 the Tang dynasty emperor Daizong decreed that, for the welfare of the empire, Manjusri should be worshipped in every Buddhist monastery in China. Each of the five peaks (or ‘terraces’) of Wutaishan became associated with a different manifestation of Manjusri; accounts of visionary encounters and apparitions abound. High-wattage “spiritual magnetism” has long attracted pilgrims from not only within China but also Mongolia, Tibet, India, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Burma and Japan (including Ennin, from Kyoto’s Enryaku-ji, who studied there in 840).

Significantly, as Wen-shing Chou points out, “The mountain’s claim for sacrality… rests chiefly on its promise of revelatory encounters in the present and future, rather than on possession of relics or other traces of the historical Buddha.” This non-specificity allows and has facilitated much reinterpretation and retextualization; her book is an important exploration of the literally geopolitical dynamics of building a “Sino-Tibeto-Mongolian Buddhist vision of a Chinese landscape,” thereby creating an effective foundation for imperial and national identity but also potent opportunities for Inner Asian interplay within that process.

The Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368), of Mongol origin, first fostered Tibetan Buddhist connections at the former Daoist stronghold of Wutaishan, a statecraft strategy further articulated by the Qing Dynasty Manchu emperors. “Having come to rule China from outside the Great Wall in northeast Asia they fashioned themselves in the role of cakravartin (literally, wheel-turning king), referring to an Indian ideal of a universal and enlightened ruler who turns the wheels of law, whose reign brings peace and justice, and an emanation of Manjusri…” Chou focuses especially on the achievements of the Qianlong emperor, who reigned from 1736 to 1795, and was linked both personally to Wutaishan (he made six pilgrimages there, including one with his mother, in celebration of their 50th and 75th birthdays, respectively, in 1761) and through his spiritual advisor, the national preceptor and polymath translator, reincarnate Gelukpa lama Rolpé Dorje (1717-1786), who spent virtually every summer on Wutai for the last 36 years of his life—a ubiquitous and intriguing presence in this large-format, generously-illustrated book.

Imperial identification with Buddhist authority was hardly new; in nearby Datong, formerly the Northern Wei capital of Pingcheng, five massive stone Buddhas dating from 460 to 465 reputedly bear more than coincidental facial resemblances to early Wei emperors. (Back story: they in fact represent emperor Wencheng’s pious efforts to restore faith in the dynasty, following the Daoist emperor Taiwu’s merciless suppression of Buddhism from 445 to 452).

Two superbly sensitive portraits of Manjusri by Qing court painter Ding Guangpen, commissioned by Qianlong, may be seen at the Palace Museum, Taipei. Chou comments: “Ding’s second painting superimposes the esoteric, and specifically Tibetan, tradition of ritual transformation and an Indian ideal of Buddhist kingship onto a Chinese Buddhist icon with a popular Mongolian cult following, visually and metaphorically reenacting the bodhisattva’s hybrid identity through Indo-Tibetan, Mongolian and Chinese iconography and history…” adding, “it would not be far-fetched to see Ding’s second painting as a portrayal of Qianlong himself.”

She also references a mandala-style thangka in the Palace Museum in Beijing, which explicitly represents Qianlong as the universalist Manjughosa Emperor (a title conferred on the Qing emperors by the fifth Dalai Lama in 1653). This image was presented to the eighth Dalai Lama in Lhasa in 1758; the emperor’s face is believed to have been painted by “Qianlong’s portraitist of choice” the Jesuit Giuseppe Castiglione (whose mission at Qianlong’s court, to proselytize Catholicism, was—as Patricia Ann Berger notes—“unrequited”).

Perhaps disingenuously, in inscriptions on steles in Shuxiang Temple on Wutai, Qianlong downplays his identification with the Bodhisattva, saying, “The Tibetan lamas call me an emanation of Manjusri based on the near homophone of ‘Manchu’ and ‘Manju,’ but if it were really true that our names correspond to the reality, wouldn’t Manjusri laugh at me for that?” (Translation by Chou).

Documenting the prodigious extent of Qianlong’s engagement with Buddhism, Chou discusses his replication of major buildings in Chengde, near Beijing (including Wutai’s Shuxiang-si, and even the Potala Palace of Lhasa), his vast textual projects (notably Rolpé Dorje’s translation of the entire Tibetan Tengyur commentaries into Mongolian, and the Chinese Tripitaka canon into Manchu) and his re-edited expansion of an imperially authoritative gazetteer of Wutaishan, as vital grounding for Tibetan and Mongolian pilgrims. She also insightfully compares two versions of the above-mentioned Cifu-si pilgrimage map (the Rubin Museum’s, and one in the National Museum of Finland, Helsinki). All these imperial projects contributed to documenting, redefining, and sometimes reinventing, the Wutai connection and consolidating its vital role in the Qing narrative.*

“By appropriating a millennium-old history of religious kinship and Pan-Asian legend of a miraculous icon at Mount Wutai, he [Qianlong] both encompassed and effectively transcended all ethnic, sectarian and linguistic affiliations of his constituents… At a time when many parts of Mongolia and Tibet had recently become part of the Qing empire, Mount Wutai thus provided the Qing Inner Asians a unique space to engage with, and to reinvent their own genealogies and identities in relation to, the history and geography of China proper.”

In her coda to this book, Chou extrapolates this as an ongoing process. “In spite of the very different realities of post-Cultural Revolution China, Mount Wutai emerges again as a gateway between China and Tibet, and one of the only places in China proper to attract Tibetan pilgrims in large numbers.”

She cites in particular the three-month 1987 pilgrimage of Khenpo Jikpun (1933-2004), the Tibetan Nyingmapa sect founder of Larung Gar Academy, in Eastern Tibet (see the photo-essay by Victoria Knobloch in KJ 84), with thousands of his disciples, as illustrating “the revisionist potentials of pilgrimage to Mount Wutai in contemporary China.” On returning home, Khenpo Jikpun “consecrated a surrogate Mount Wutai in the hills behind the Larung Gar Academy… continuing a tradition of creating visual, architectural, and spatial ‘replicas’ of Mount Wutai that began as early as the pilgrimage cult of Mount Wutai itself in the seventh century.”

* Not pertaining directly to this book’s scope of inquiry, only passing reference is made to the emperor Qianlong’s vast Four Treasures project (Siku Quanshu). Between 1773-1782, a 361-member editorial board requisitioned all of the aristocracy’s private libraries (returning most items, with the addition of valued imperial colophons, while destroying works that were deemed heretical) to select an immense anthology of classic literature, dwarfing the compendium created by the preceding Ming Dynasty. The project produced no less than 36,381 volumes, incorporating 3,461 complete works, in 2.3 million pages. Seven sets were created in total, all handwritten, by 3,826 scribes. Today only four of these sets remain.

See Ken Rodgers’ associated photos from his journey to Wutaishan in summer 2018 here.

Worth noting as a companion publication is Nomads on Pilgrimage: Mongols on Wutai-shan (China) 1800–1940, by Isabelle Charleux (Brill, 2015). See also Building a Sacred Mountain, Wei-Ching Lin (University of Washington Press, 2014), covering architectural developments, 3rd through 10th centuries, and Empire of Emptiness: Buddhist Art and Political Authority in Qing China, Patricia Ann Berger (University of Hawaii Press, 2003). For a comprehensive guide to Wutai’s history, lore and sacred sites, seek out the massive (2.4kg) China’s Holy Mountain: An Illustrated Journey into the Heart of Buddhism, by Christopher Baumer (I.B. Tauris, 2011). (Well worth taking with you if you visit Wutai—but not in your daypack when climbing the 1,080 stone steps up to Dailuoding…)

Ken Rodgers is KJ’s Managing Editor.

Portrait of the Qianlong Emperor as the Bodhisattva Manjusri (Detail)

Qing Imperial Workshop, with face by Giuseppe Castiglione

Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution

http://projects.mcah.columbia.edu/nanxuntu/html/emperors/manjusri.htm